Comic books are not just a joke

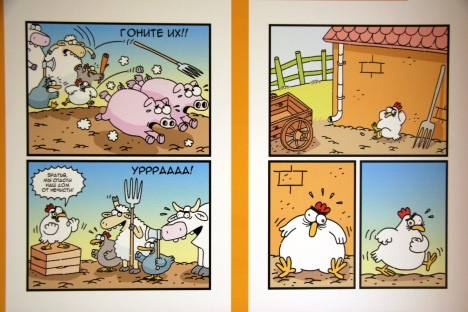

A photo of a comic book presented at the international comics festival ComMission held in Moscow. Captions to the cartoons: 1. Chase them away! 2. "Brothers, we have saved our home from the vermin" - "Cheers!". Photo by Tatyana Shramchenko

A few years ago, no one talked about the comic book industry in Russia – there was nothing to talk about. The Russian reader prides himself on being part of the “most read nation in the world” but reading comics is not considered reading. Stories in pictures are very closely associated with mass lower-grade literature.

For comic enthusiasts, challenging this stereotype and teaching the language of comic books to the masses is a complicated task, especially when it comes to the older generation. Younger Russian readers, however, seem increasingly interested in this segment of pop culture.

Related:

Since 2002, Moscow has hosted the international comics festival ComMission. It began as an amateur art project, but gradually evolved into a significant cultural event. In 2009, it added a separate social project called Respect. A worldwide project involving comic fans and artists from Belgium, Germany, Spain, Ukraine and the UK, Respect uses comic books to draw attention to pressing social issues. In Russia, it also works to combat the view that comics are shallow.

According to the organizers, Respect “primarily targets the younger audience, because it is in this environment that social tensions most often result in outbreaks of violence. Comics are the most successful language for speaking about tolerance, because authors of comic books are used to working simultaneously with a message, text and image and are positively perceived by the youth.”

Mission 2012

This year’s ComMission festival was held from April 27-May 27 and the Respect project showcased works by 22 artists. Foreign comics were translated into Russian for the event. Each artist spoke about his concerns, and the selection of works was quite diverse and topical

Russian artists focused mainly on political power, immigration and nationalism. Konstantin Komardin presented “Legitimate Government,” an illustrated allegory about the imposition of authority on society. In the piece, a group of earthlings arrives on an unknown planet and discovers a highly developed peaceful civilization, which isn’t familiar with the institution of political power. The astronauts teach the locals to “elect a president,” introducing not only the concept of authority, but also conflict.

Khikhus, 44, Russia’s best-known comic artist, told a story about the genocide of fish – people and fish used to live together, but one day the president decided that fish should be blamed for all the misfortunes of humankind and decided to cleanse the country of them, sending them all to special underwater camps.

Belgian artist Thierry Bouüaert, 48, brought a comic book describing a civil war resulting from ethnic conflicts. The plot is about a war in some “abstract European country,” during which the two protagonists, a Walloon and a Frenchman, gradually change from enemies to friends. The artist is currently working on a comic book on Russian youth in the 1990s.

Blogger stixdan, a journalism student in St. Petersburg, is positive about the influence of comics. “I know about 50 highly skilled comic artists in Russia. However, if you search all over the Russian regions, you will definitely come across many unknown comic book fans, real top guns in comics, who, unfortunately, can only draw comics and sharpen their skills in their free time. They make their living just like any other comic artist in Russia, by illustrating books and magazines, making storyboards for films and developing art concepts for the media (mostly video games,” he said.

Now, major Russian publishing houses such as Azbuka, Exmo, Rosmen and ACT are getting interested in comic books, but many fans find their plans for the genre ill-conceived: comic books are published in limited collector’s editions and are too expensive for the mainstream audience. The business is mostly based on purchasing licenses to print foreign comic books in Russia, while many original projects without big names are still published at the amateur level and are only distributed in small circles.

For the publishers, however, it is more profitable to pay $5 per page for a hit comic than to pay $300-400 per strip to local artists. The comic publishing process is quite labor intensive. It takes a couple of days for a professional artist to draw a good high-quality strip, but only if it is his primary job. And business is business. Comics are not yet popular in Russia and it is hard to make money off them.

But the organizers of ComMission hope that as comics become more known in Russia, the demand for them will create the need for quality, local strips.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox