Newfound religious fervour has little mass appeal

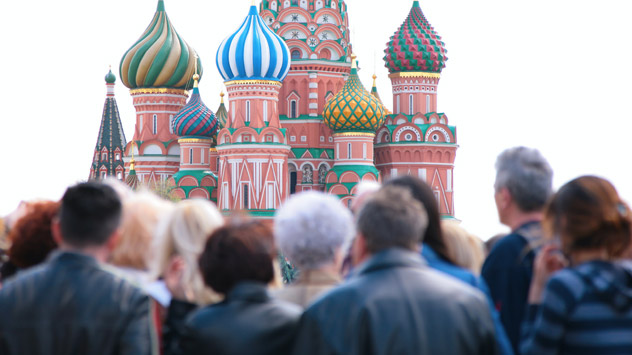

Religious freedom is almost absolute in Russia in the 21st century. Source: ITAR-TASS

On a long train journey somewhere in the Siberian hinterland, I met a Dagestani conscripted soldier who was assigned an army unit near Novosibirsk. He was proud of his Muslim heritage but laughed when I asked him if he fasted during Ramadan or avoided pork and alcohol. The soldier said he’d starve if he didn’t eat pork while serving in the army. It would also be very “un-Russian” to not drink with comrades, who shared his fate as conscripts. The young man had never set foot inside a mosque and the stories I heard about his life in the largely Muslim Republic of Dagestan would shock the quasi-puritan religious leaders of Russia.

It’s not just the Muslims in Russia who frown at open display of religious zeal, most Russians tend to be agnostic (not atheist like some put it). Despite attempts by religious leaders to mobilise people on the basis of a “heritage,” beliefs remain largely a private affair in the country. I have gone many times to the church where Pussy Riot displayed their “hooliganism.” While the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour is beautiful, when it comes to “spiritual energy,” it is hardly any different from the magnificent cathedrals of Europe, which have more tourists than pilgrims.

From my own experiences, I can say that most Orthodox Churches in Russia when conducting prayer services have an odd mix of babushkas (grandmothers), very rich businessmen, a smattering of nationalists and the occasional curious onlooker. Although personally agnostic, I like the mystic Russian Orthodox Church. The older monasteries in places like Valaam, Borovsk and Sergiyev Posad have a calming effect on those dealing with the heaviness of Russian life. However, there is always one question that boggles visitors to Russia’s churches: “Where are the young people?”

When I first moved to Russia in 2003, I went to an Orthodox Church accompanied by a local friend. Most of the faithful in the church were happy to see a foreigner taking an interest in the Orthodox faith, but they didn’t express similar sentiments towards my friend. She covered her head as she entered the church, but growing up in an agnostic home, she had no clue as to how to pray and the resident babushkas gave her several disapproving glances until we left the church. That was my Russian friend’s first and last visit to an Orthodox Church as a “believer.”

Despite being largely agnostic, Russians tend to be open-minded to diverse religious ideas and beliefs. It is very trendy to be Buddhist and vegetarian in many circles these days. I have also seen how dedicated Russian followers of the Hare Krishna movement are. Even at the time when the Orthodox Church was at the helm of affairs in the country in Czarist Russia, artists and philosophers like Nicholas Roerich who had deep inclinations to the ‘East,’ appealed to a large section of Russians.

Religious freedom is almost absolute in Russia in the 21st century, but religious leaders are always on the lookout to mobilise the masses and to create some sort of new pan-religious identity in the country. These leaders have made in-roads with decision makers, who want to draft laws that call for severe punishments against those that offend religious beliefs. I agree that the law should come down hard on those that deliberately incite religious hatred or those who attack people or religious symbols. However, one has to really look at the merits of paying too much attention to idiots.

Many of my Russian friends are debating whether the ban on ‘Innocence of Muslims,’ is justified. Human stupidity has no limits whatsoever and I personally feel that the best way to deal with garbage like that film is to not dignify it with the slightest bit of attention. I remember when Russia banned the film ‘Borat’ as it was termed offensive to ‘Kazakhs.’ Nursultan Nazarbayev, the President of Kazakhstan, did not follow suit and claimed that there was no such thing as bad publicity. Interestingly enough, the ban made the film one of the most downloaded in Russia.

Many religious leaders in Russia live in a time-warp called the 19th century, where religion played a major role in public life and was even the cause of the disastrous Crimean War. Given the agnostic beliefs of the majority, the Russia of today is hardly a place where religious sentiment can be whipped up and mobilised for political gain or other vested interests.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox