A look inside the salt mines of Perm

Unlike the coal mines of Vorkuta, Berezniki mines employ women for underground work as engineering and technical specialists, for the maintenance of infrastructure. Source: Denis Vyshinsky / Kommersant

Ever since the Verkhnekamsk potash deposit was discovered in the Perm region in the early 20th century, potash salt – an indispensable natural fertilizer – has literally become the salt of the earth in Perm. Geologists believe that the deposit was formed on the site of the Perm Sea, which dried up millions of years ago. Thanks to that very same sea, Russia currently accounts for 35 percent of the world’s supply of potash salt.

The country started developing the deposit in 1925; the potash industry was one of the top priorities for some of the early Soviet five-year plans. Potash was mostly produced and processed in two towns – Solikamsk, established in the 15th century, and Berezniki, which was founded on one of the mines in 1932.Russians have different words for coal mines (shakhta) and potash mines (rudnik). There may be some differences in the actual mining procedures, but it seems that the difference is mostly semantic.

The cage at the Berezniki salt mine has a capacity of 85 miners, so it resembles an underground subway car during rush hour. More than 600 miners work in the mine per shift. There are a few women with wooden yard sticks in the cage – they must be surveyors. Unlike the coal mines of Vorkuta, Berezniki mines employ women for underground work as engineering and technical specialists, for the maintenance of infrastructure.

The cage, which could also as easily bring down a truckload of cement, descends to the quarter-mile mark, and workers take their seats in the vans that will take them to their assigned sections. They are traveling 5.5 miles away from the point of descent.

On the surface they warn that a salt mine is markedly different from a coal mine. This is true: here, miners tread on a dry, smooth “floor,” instead of the slush of wet coal dust. Stalactites hang from the roof in older sections. This mine is drier, cleaner and brighter. “This is salt,” chief engineer Oleg Voronin says, pointing at the floor and the walls. “We have descended to the layer that is called ‘salt,’ so the thing we are walking on now is rock salt.” When the thick grey dust on the wall is scratched off, the white salt is visible. There is no need to lay rails in a salt mine – workers can use a car to drive in these wide, dry tunnels. The miners are delivered to their workplaces in stubby Krot vans. In a regular UAZ van, Voronin drives into the “red” layer, where sylvinite ore accounts for the reddish color of the walls there.

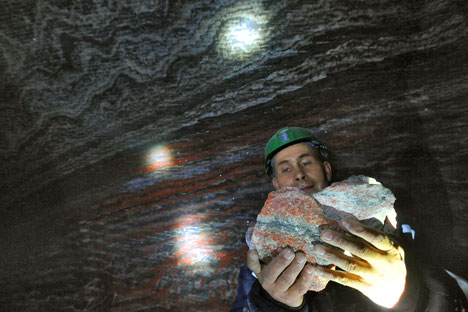

Many colors of the minerals. Source: Denis Vyshinsky / Kommersant

Streaks of minerals run on the walls, often making beautiful patterns: the crude rock coming from the mine is mostly potash salt mixed with clay and rock salt, but there are also magnesium and calcium salts here. Methane emission rates are much lower here than in a coal mine, and the main enemy of a potash mine is water. Should water come through water-retaining layers in the geological anomaly, it could flood the mine.

There is a Ural-20R mining machine at one of the sites. It appears that these behemoths are used in most salt mines. A self-propelled car follows the mining machine: it is a 30-ton truck that receives rock from the machine and takes it to the well, where they drop it onto the conveyor.

The mining machine takes only five minutes to fill the truck. If the drop point is close enough and the machine does not stand idle for too long, the machine operator and car driver are capable of taking more than 1,000 tons of rock to the conveyor during a single 8-hour shift. As it makes progress through rock, the machine drills vertical holes in the roof to release gas and reduce the stress on the roof. To strengthen the roof, bolts are driven into it – they hold down the roof without requiring additional braces.

Salt mines do not have the wooden posts that are seen in standard coal mines, and gangplanks never collapse in caved-in areas after drifting. The mine is a giant layer-cake of drifts located at various levels. There are around 1,000 drifts here.

The underground stockroom is a large cave 984 feet long, 52 feet high and 55 feet wide. Source: Denis Vyshinsky / Kommersant

The underground stockroom is a large cave 984 feet long, 52 feet high and 55 feet wide. Powerful yellow lamps illuminate the red rock. The cave looks like a film studio shooting “The Martian Chronicles.” Holes in the roof are hiding in plain sight – these are the wells used to drop rock from the upper layers. This cave has a capacity of 30,000 tons of rock. From time to time, rock is taken up to the surface, but first it needs to be dropped even deeper onto the conveyor.

The rock from the mine is then delivered to the processing plant. There are two methods of producing pure concentrated Muriate of Potash (MOP): chemical enrichment, which is based on various salt dissolubility rates; and floatation, which is based on adding water to potash salt. The former method produces white powder with an MOP concentration exceeding 98 percent; it is used especially to make compound fertilizers. Both methods are employed to make products with MOP content of 95 percent or more, which is enough to apply fertilizers in fields.

The next stop is the floatation plant, which also makes granulated MOP for easier fertilizer application. According to the head of the floatation plant, Andrei Mosunov, granulated MOP is becoming more popular and currently accounts for half of his plant’s output. Andrei goes over the entire production chain – from the degradation and separation of rock, to drying and granulation. The entire plant is covered in salt dust and there are pools on the floor; but this is brine, not water. The equipment here is washed (also with brine).

After the separation is completed, waste rock is taken either to the dump or back to the mine to fill in the stripped areas. There is reddish powder on the other conveyor belt. This is MOP with 6-percent moisture content. The warm reddish pellets also taste salty, but MOP adds a hint of bitterness.

There are huge hills near the plant; these are salt dumps that have been accumulating since the mine was launched. This waste can be sold to utility services for anti-icing procedures. Some workers believe that the salt dump is full of gold and other rare elements – nearly everything on the periodic table. Miners say the Chinese wanted to buy it all and take it back home with them, but their offer was turned down. “I heard this story back in 1972, when I started working here,” says the mine’s operations director, Boris Serebrennikov, laughing. “But it was the Japanese then, and not the Chinese.”

First published in Russian in Kommersant Dengi.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox