A short history of British tourism in Imperial Russia

It was St Petersburg, founded in 1703, that was to prove the great tourist attraction. Source: Bridgeman

British tourism in Russia was certainly not invented by Intourist during the Cold War. An otherwise tragic expedition to discover a northern sea route first brought the English to Muscovy in the middle of the 16th century and it was essentially trade and profit that inspired further embassies and led to the establishment of a Russia Company to exploit that trade. However the concept of travelling for pleasure or what was often termed “out of curiosity” was much undertaken in the ancient world. What was new was travelling to barbaric, wild Russia, land of snow and bears and wolves, and of peoples with the strangest habits and, as an Englishman would have it, ‘to vices vile inclin’d”.

The Grand Tour goes East

The 17th century saw the emergence in Britain of the Grand Tour, when young members of the aristocracy and gentry travelled through Europe, usually accompanied by tutors. Although Dr Samuel Johnson might suggest that “the grand object of travelling is to see the shores of the Mediterranean”, the northern lands increasingly beckoned more intrepid travellers.

British tavellers in Russia. Source: Anthony Cross

It was St Petersburg, founded in 1703, that was to prove the great tourist attraction, fulfilling the hopes of its first Governor-General Prince Alexander Menshikov that it “should become another Venice, to see which Foreigners would travel thither purely out of curiosity”. One of the first Englishmen to be so attracted some three decades after its foundation recorded in his diary that “I am well contented with my journey, and think it very much, worth any curious man’s while, going to See, and to Stay there three weeks or a month, but after Curiosity is Satisfied, I think one could amuse oneself better, in more Southern Climates”.

By the end of the 18th century, another traveller was writing that “Russia begins now to make a part of the grand tour, and not the least curious or useful part of it”. The British tourist was also beginning to explore other parts of the rapidly growing Russian empire, travelling south via Moscow to Russia’s newly acquired territories around the Black Sea and in the Crimea, often travelling on to Constantinople.

Pioneering lady

Lady Elizabeth Craven was the first English woman to publish an account of her journey, helping to boost the appeal of the Crimea and newly founded Odessa for a growing stream of travellers up to the Crimean War. A remarkable journey was undertaken towards the end of the reign of Catherine the Great by a young English milord, accompanied by his Oxford tutor, John Parkinson, who recorded in diaries their epic journey to Siberia as far as Tobolsk and then south to Astrakhan and the Caspian and the edge of the Caucasus before crossing to the Crimea and returning through Ukraine to Moscow and St Petersburg.

Russia’s first tour guides

As the Grand Tour gave way to middle-class tourism, an indication that Russia was indeed beginning to appeal to a wider public was the appearance of the ‘tourist guide’.

By the late 1830s there had appeared a Guide to St. Petersburg & Moscow, by Hamburg, and by steam-packet, across the Baltic to Cronstadt; fully detailing every form and expense from London-Bridge to St. Petersburg. It was soon followed by the first ‘Murray’ for Russia in 1839 which was several times updated, and ultimately, by the first English-language Baedeker guide to Russia, appearing in 1914 and offering information that was soon to be made obsolete and irrelevant by World War I and the October Revolution. It was reprinted in 1971 as an historical curiosity.

Ascent to the Caucasus

|

| 'The Frosty Caucasus' cover, 1876 |

Following Russia’s further territorial acquisitions in the 19th century, Georgia, the Caucasus, Circassia, and Bessarabia joined Siberia, even Kamchatka, became favoured destinations for intrepid tourists and better prepared explorers. Among them were a striking number of members of the Royal Geographical Society. In the early 1840s Sir Roderick Murchison, soon to become the Society’s long-serving president, travelled extensively through the Urals, producing a work of lasting value on the geology of the region. His achievement was matched by another future president, the geographer and mountaineer Douglas Freshfield, who first climbed in the Caucasus in 1868, conquered Mts Kazbek and Elbruz, and published by the end of the century his monumental account of The Exploration of the Caucasus.

The Caucasus became a magnet for followers of mountaineering, which had gained increasing popularity in Britain following the establishment of the Alpine Club of London in 1857. One of the club’s early presidents published The Frosty Caucasus, recounting his tramps through the Caucasus in 1874.

Welcome to Siberia

Railways opened Russia to the tourist, particularly the Trans-Siberian and the Transcaspian. Begun in 1879, a few years before the Trans-Siberian, the Transcaspian railway followed the route of the Silk Road from its terminus at the harbour of Krasnovodsk on the Caspian via Bokhara to Samarkand, which had become part of the Russian empire in 1868. By the end of the century it was extended to Tashkent, which became the capital of Russian Turkistan soon after its seizure in 1865.

The Trans-Siberian caught the imagination, however. Begun in 1890 but only completed in 1916, it was the great ‘ribbon of iron’ along which the anthropologist and translator Annette Meakin travelled towards Vladivostok with her mother in 1900, the first Englishwomen to accomplish that journey. In 1900 the journey still involved a ferry ride across Lake Baikal on new steel-hulled ice-breaking boats that had been built in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and it was only in 1904 after horrendous difficulties in construction that the Circum-Baikal railway was completed and it became possible to travel the whole route by rail.

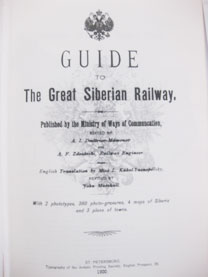

|

| 'Guide to the Great Siberian

Railway' cover, 1900 |

In 1900, the Russian Ministry of Ways of Communication published an English-language Guide to the Great Siberian Railway that described in exhaustive detail the main railway and all its connecting lines, with over 350 photographs. If its aim was to entice Anglo-American tourists to journey along the whole length of the railway then it succeeded. There are literally dozens of accounts from the first two decades of Nicholas’s reign about journeys on the Trans-Siberian.

By the 1890s cyclists were pedalling their way through Russia. Sir John Foster Fraser and friends cycled from Odessa through the Crimea and the Caucasus as part of a world tour that took 774 days. British cycling enthusiast Robert Jefferson claimed a record for his round trip from Warsaw to Moscow in 50 days in 1895. Returning three years later, and accompanied by Russian cycling friends, he followed the Volga and, crossing the Kirgkiz steppe, eventually reached Khiva, where he was received by the Khan.

A tea party in a Kirhis tent. Source: Anthony Cross

The war and the events of 1917 effectively put paid to British tourism, but by then it can be said that the British had penetrated virtually every corner of the Russian empire. Present-day tourism again offers fantastic opportunities to explore a vast country, but you may well find that wherever you go, a British traveller or tourist has been there long before you.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox