Moscow museums taking steps to help visitors with disabilities

The naked bronze man by Antony Gormley and its plaster replica.

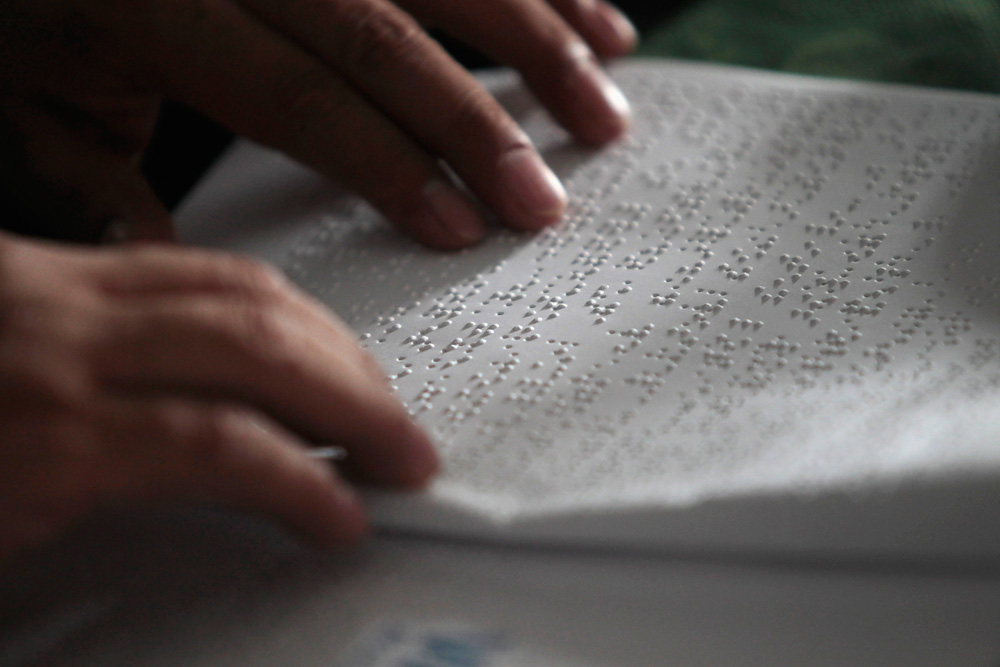

Press PhotoThe naked bronze man created by British sculptor Antony Gormley defies gravity as it stands on the museum wall, leaning 45 degrees towards the viewer. Nearby is its plaster replica, which is 10 times smaller and can be touched. There are also headphones and a piece of paper with dots – a text on the exhibit in Braille.

This is the Co-thinkers exhibition, on at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow until Sept. 9. The exhibition is the first of its kind in Russia to view the concept of inclusion as part of the art process and not the infrastructure.

The exhibition's co-curators were four museum visitors with various handicaps: Yevgeny Lyapin, who moves around in a wheelchair, Yelizaveta Morozova, who has Asperger syndrome, Polina Sineva, who has been deaf since childhood, and Yelena Fedoseyeva, who has been blind since the age of 13. In collaboration with the museum's curators they have selected works of art and conceived architecture and the exhibition's content using their sensations and visual perception experience.

With the powers of art

"I selected emotionally mixed works, which can be interpreted in various ways. The more conflictive the art, the better. Since leaving the comfort zone always leads to development," explained Lyapin. In his view, art's essence in itself can be considered as a manifestation of inclusion.

"Art destroys stereotypes and taboos, liberating society – such is mental inclusion. In a way this is what unites contemporary art and invalidity. At first glance everything incomprehensible appears frightening to people."

The museum's halls have been adapted for people with various handicaps: All exhibits are accompanied by an interactive module that includes tactile materials, audio descriptions and sign language videos with comments by the curators and "co-thinkers."

"The idea of exhibition modules that unite various ways of perceiving art is a completely new practice. Its success will be understood very soon," said Fedoseyeva.

Accessibility by form

The first department of inclusive programs in Russia has been operating at Garage for a year now. "Our intention is not only to guarantee physical accessibility to the museum but also to understand what having a handicap means, to interact with other museums," said program coordinator Maria Sarycheva, for whom Garage's reference points are the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the Tate Gallery in London.

However, many Moscow museums are still far from inclusive even on the level of physical accessibility. The Moscow Administration Department of Culture claims this is related to “the architectural specifics of the museum buildings, which are architectural monuments.”“It is impossible to technically equip them with support handrails along the buildings' entire perimeter and install elevators for people in wheelchairs," said the department’s press office, ignoring the fact that many of Europe’s great museums inhabit buildings that are several hundred years old and this does not obstruct the installation of equipment for the disabled.

"It is still very early to speak of inclusion in Moscow's museums," said Kamilya Tabeyeva, director of the National Foundation for Rehabilitation Development. "Interactive programs are a rarity and visits for the handicapped are arranged with the museums separately."

In terms of the museums' accessibility, Yelena Fedoseeva agrees that inclusion in Moscow museums is still not systematic: "Usually there are programs for the handicapped, but they do not adapt the entire space, just its separate elements, or they are designed for holding special events," she said.

Museums opening up

Nevertheless, there are successful examples, such as the Darvinovsky Museum, which was the first museum in Russia to make its space fully accessible to all categories of visitors. The museum has equipped ramps, the exhibition descriptions are also available in Braille and special programs and itineraries are always accessible, not only by appointment.

Among other handicap-friendly places is the Moscow Planetarium, which is equipped with interactive modules and is well adapted for visitors with limited mobility.

Elsewhere in the capital, the Tsaritsyno Museum-Reserve is well organized for blind visitors. It has tablets with special apps that help blind people orientate themselves in the exhibition space without assistance from others, an openly accessible room with a collection of exhibits for tactile appreciation, and programs developed with the participation of museum collaborator Alexander Novikov, who is blind.

The Tretyakov Gallery offers its deaf visitors and those hard of hearing a video guide with sign language and visitors with limited mobility special chairs that fit in elevators. Moreover, the Tretyakov building on Krymsky Val, which contains the famous Russian avant-garde collection, regularly organizes exhibitions as part of the Language of Sculpture in Braille project. The works that are created especially for the project can be "admired" with one's hands, then one can read a label with a Braille text and listen to an audio guide.

In the opinion of Maria Sarycheva, in general museums change along with society, and now Russian museums are at a point where they are ready to accept the previously "invisible" visitors.

"Inclusion is the absence of separating people according to their form of handicap. The fact that two people move about in wheelchairs does not make them friends. People are united by common interests, cultural events, tastes. The museum is a point of contact for lovers of art, independently of the condition of their health," she said.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox