How a Ural mayor gathered the biggest collection of secretly-made Old Believer icons

The former head of Yekaterinburg Evgeny Roizman

Ulf Mauder/Global Look PressAs strange as it sounds, during the Imperial Era, you could have been killed for painting these icons. Now worth hundreds of thousands of dollars on the market, in terms of art and cultural history, they’re priceless.

This story begins in the 1650s, when the Russian Orthodox Church split into two parts: the Old Believers, who adhered to ancient Russian liturgical rules and texts; and the New Believers, who followed Patriarch Nikon’s liturgical reforms. With the Russian state firmly behind Nikon and the official Orthodox Church, the Old Believers were declared heretics and severely persecuted for their beliefs.

Alexei Kivshenko. "Patriarch Nikon. Revising Service-Books" 1880

Public domainLife as an Old Believer meant possible forced conversion to mainstream Orthodoxy, but an even harsher persecution awaited those who painted the Old Believers’ icons. One key element in Nikon’s reform was changing the rules of Orthodox icon painting, and the Patriarch demanded that the procedure remain true to the Greek originals. This is why many old Russian icons were banned.

Some icons even faced a ban after Nikon. Saint Christopher had been traditionally depicted with a dog’s head, and venerated in this form by the Old Believers. In 1722, however, the official church ordered to paint him with a human head. Nevertheless, the Old Believers continued to adhere to the old way of painting this icon.

The painting "Boyarynia Morozova" by Vasily Surikov. Feodosia Morozova was one of the best-known partisans of the Old Believer movement

Tretyakov GalleryAll of these ‘new’ icons were considered heretical, which is why Old Believers were ready to pay large sums to those who created them – skilled artists who risked their health and freedom. It’s indeed difficult for us today to fully comprehend the importance of these sacred images to believers.

In the late 1990s, experts realized that icons from the small Ural city of Nevyansk were the pinnacle of the Old Believers’ religious art. Over the course of many years, Evgeny Roizman, a former mayor of Yekaterinburg put together the largest collection of Old Believer icons; the earliest of his icons date to 1734, while the last dates to 1919.

Evgeny Roizman in his Museum (Yekaterinburg). Near the earliest Nevyansk icons. Icon of "The Mother of God of Egypt" is in the center (the earliest known icon of 1734).

Press photo“I even found an Old Believer icon painter, who said he had worked until 1934,” said Roizman. “Nevyansk was the last purely Russian icon-painting school, not influenced by European art traditions.”

Why are Nevyansk icons so special?

The style of icon painting known as ‘Nevyansk’ originated in the early 18th century and got a new lease on life in the early 19th century, thanks to industrial development in the Urals. With orders from rich factory owners, merchants and goldmine owners, many of whom were secretly Old Believers, Nevyansk masters created magnificent masterpieces of religious art.

Nevyansk itself was a small Old Believers’ settlement where there were just a few workshops. Life was tough for the icon painters: the police conducted regular roundups and searches, and the masters had to hide their instruments and icons.

These religious artists didn't paint to sell; they painted only when they had concrete orders from the Old Believers. If there were none, then they didn't paint at all.

Today, not many Nevyansk icons have survived and Roizman’s collection is the largest of its kind in the world. These icons are marked by the fact that they’re lavish and visually rich in execution and in materials.

How a former mayor built a rare collection

Evgeny Roizman says his interest in the Old Believers’ icons first sparked when he was just 15. In 1999, Roizman established the Nevyansk Icon Museum in Yekaterinburg and opened the unique collection to the public. Because of this, Nevyansk icons have become part of the canon of Russian art history.

“Because of persecution, these icons served as an instrument of self-identification for the Old Believers,” adds Roizman. “The icons determined who was a part of their community and who was outside it.”

These icons were also a means of visual agitation of Old Believer beliefs. Take, for example, ‘The Beheading of John the Baptist’. From the point of view of the Old Believers, when the Orthodox Church adopted the modernized faith in the mid 17th century, the Church was considered to have been “beheaded”.

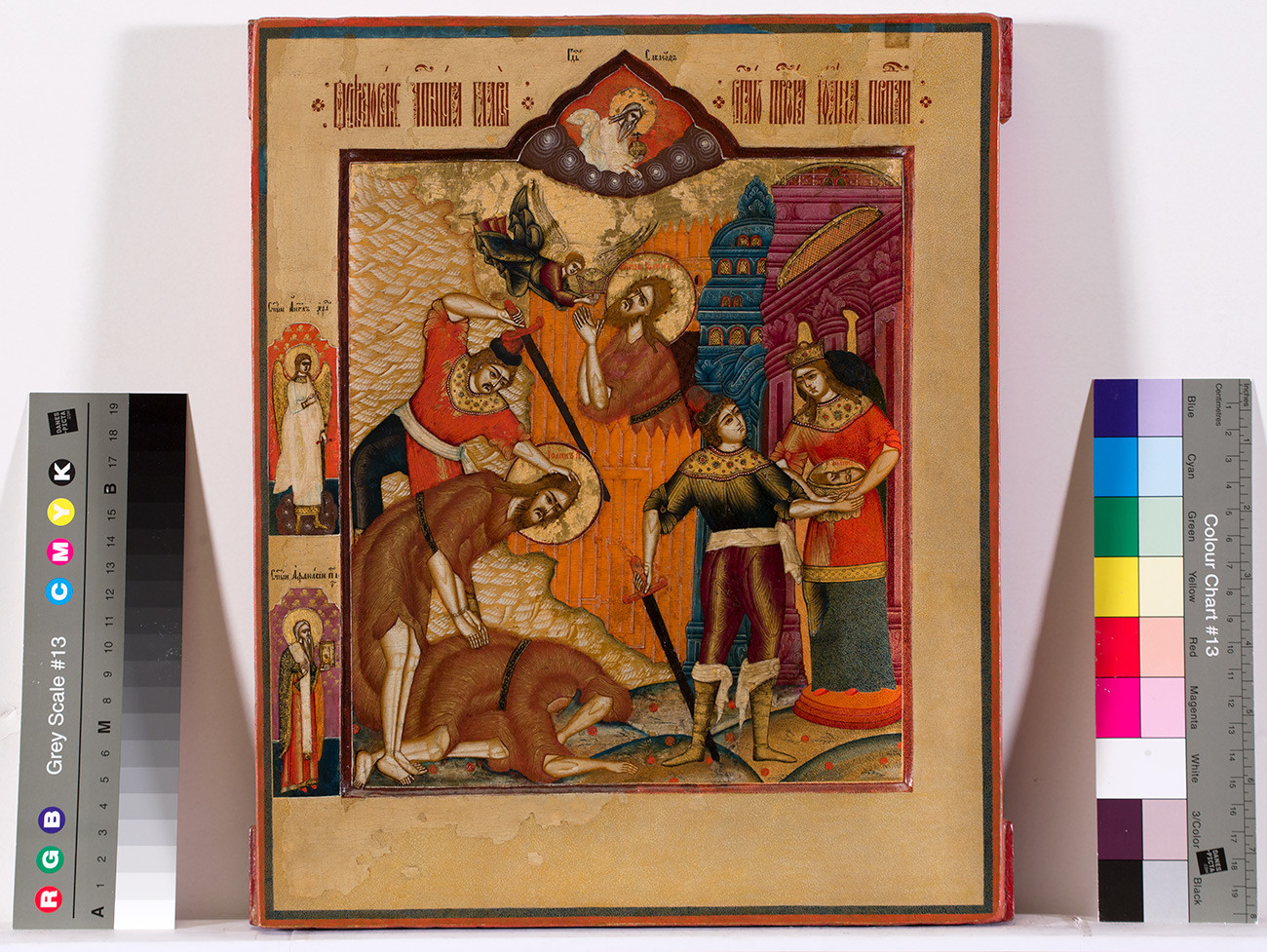

"Beheading of John the Baptist" after restoration

Press photo

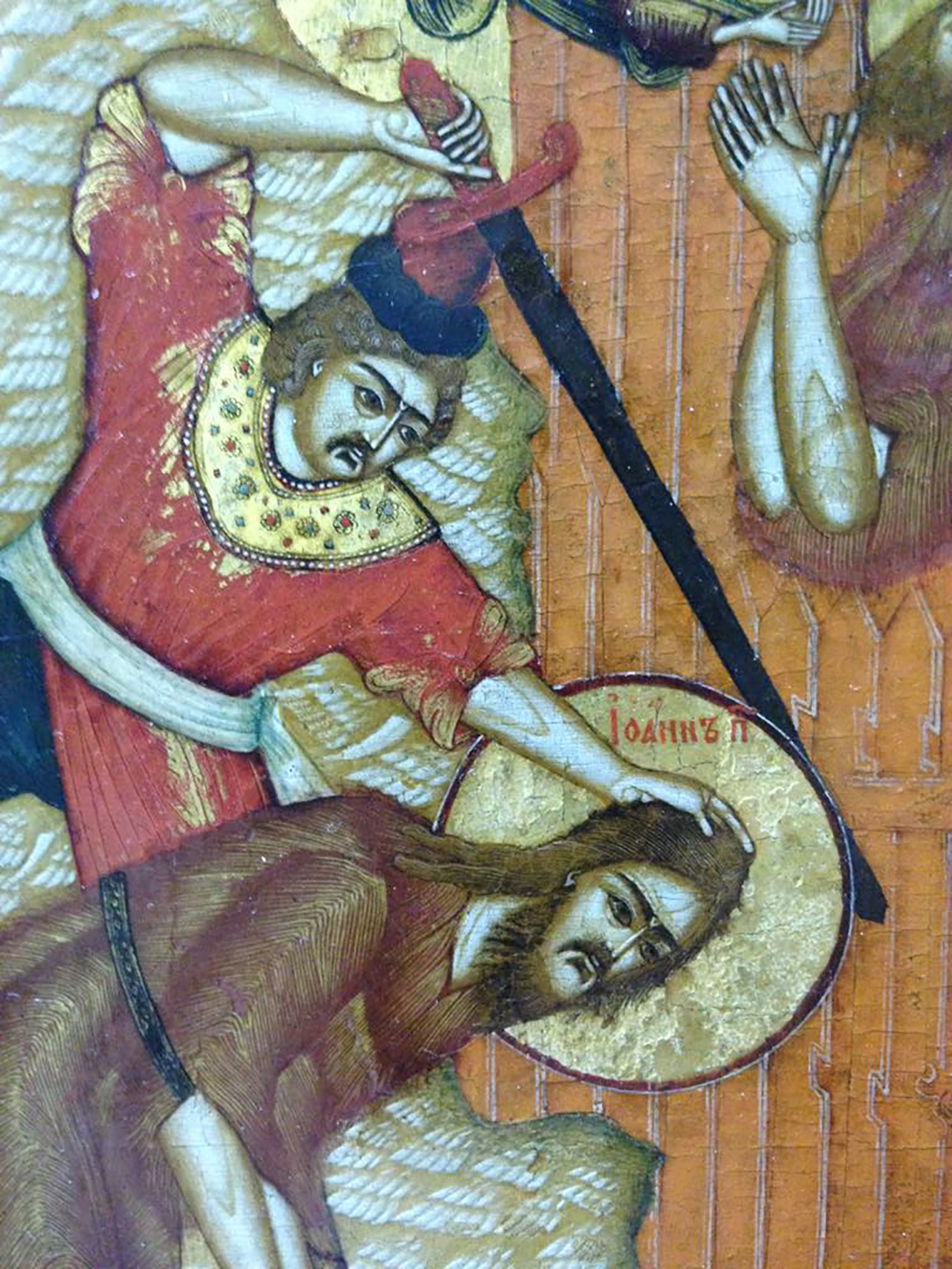

Fragment of the same icon

Press photoSome icons have exquisite details that can only be seen under a microscope. “For example, each horse’s hair over the hooves are traced in gold, as is each detail on the priest’s robe,” says Roizman.

“The Nevyansk icon painting is an entirely separate phenomenon of Russian culture and we can find the entire period of its existence in the Evgeny Roizman icon collection,” said Elena Lavrentyeva, an icon restorer at the State Research Institute for Restoration in Moscow. “He has dozens of the earliest Nevyansk icons, from the first half of the 18th century, which are almost impossible to find in state museums and other collections; as far as we know, only two early Nevyansk icons are in Russian state museums.”

Examining under the microscope the icon of "The Mother of God of Egypt" in State Research Institute for Restoration (Moscow).

Press photo

Macro-photo. Fragment of the Christ' face. The same icon ("The Mother of God of Egypt")

Press photo

Macro-photo. The Virgin's lips. The same icon.

Press photo

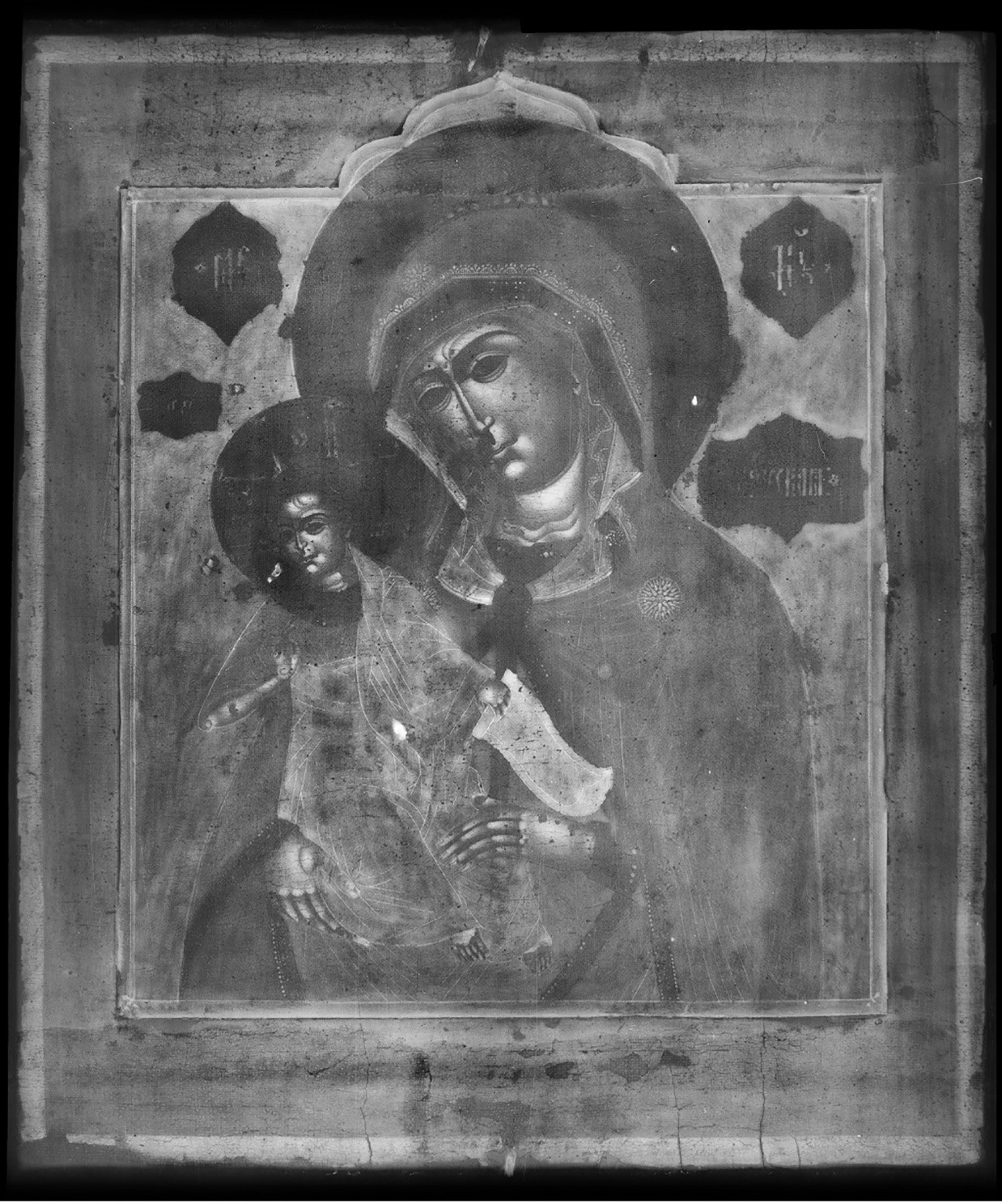

X-rays photo. The same icon.

Press photo

There is a match nearby to compare the size of figures

Press photoLavrentyeva has been working on the collection for six months and has established that almost all of the early Nevyansk icons of the first half of the 18th century were painted using the same pigments — about 10 pigments in total. When painting the saints’ faces, the early and mid 18th century Nevyansk masters used to use techniques similar to Moscow masters - repeated alternations of layers of so-called “belila” (white paint) and “okhra” (yellow ocher).”

“Chemical analysis of the pigments proves that early 18th century icon painters in the Urals used synthetic azurite, indigo, cinnabar, red lead, red organic pigment, and various types of ocher,” says Lavrentyeva, adding that they also covered the backgrounds of icons and saints’ halos with the so-called “dvoinik” - a thin leaf of silver fused with a thin leaf of gold.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox