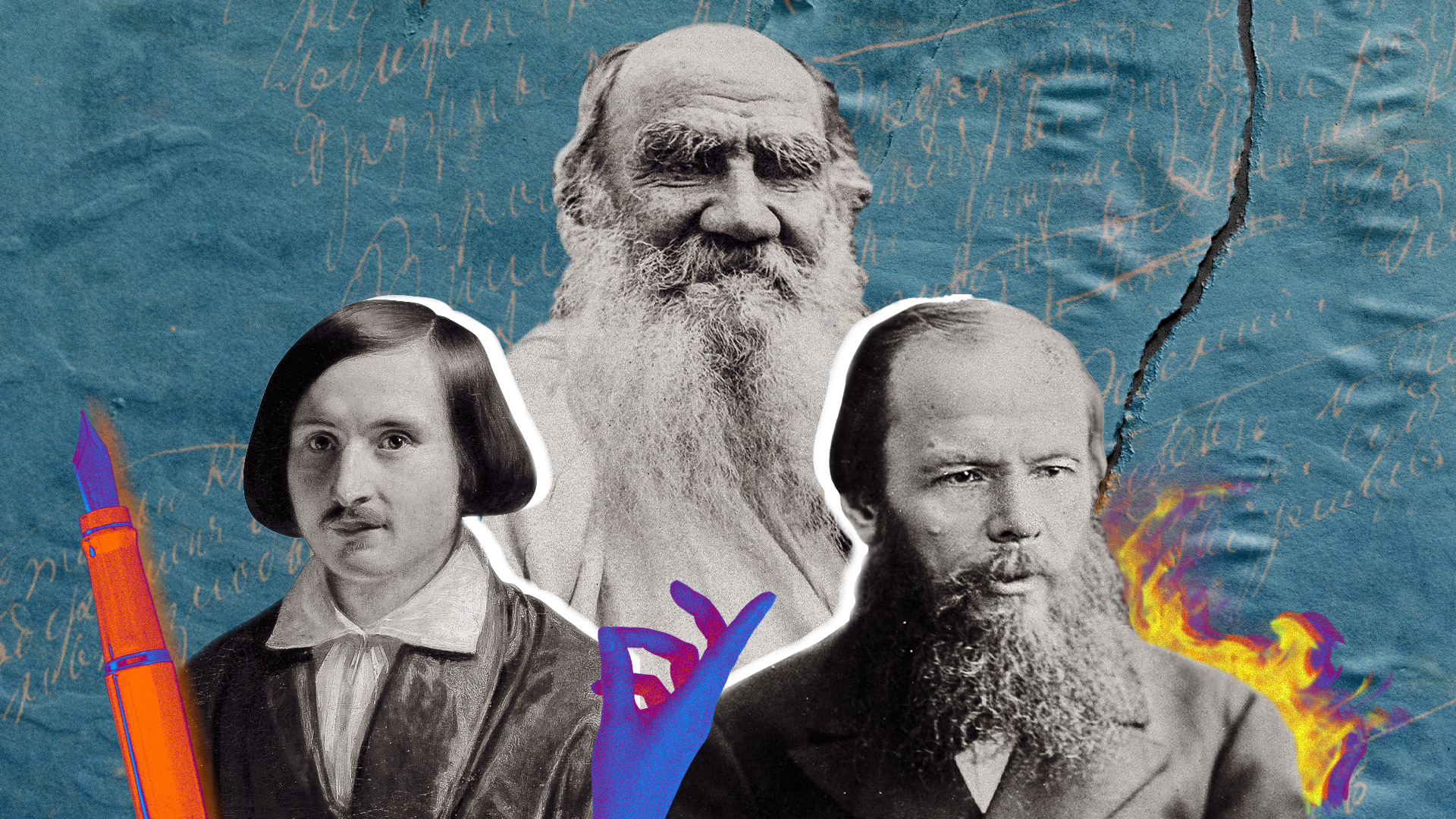

Mikhail Bulgakov, the most UNSOVIET Soviet writer

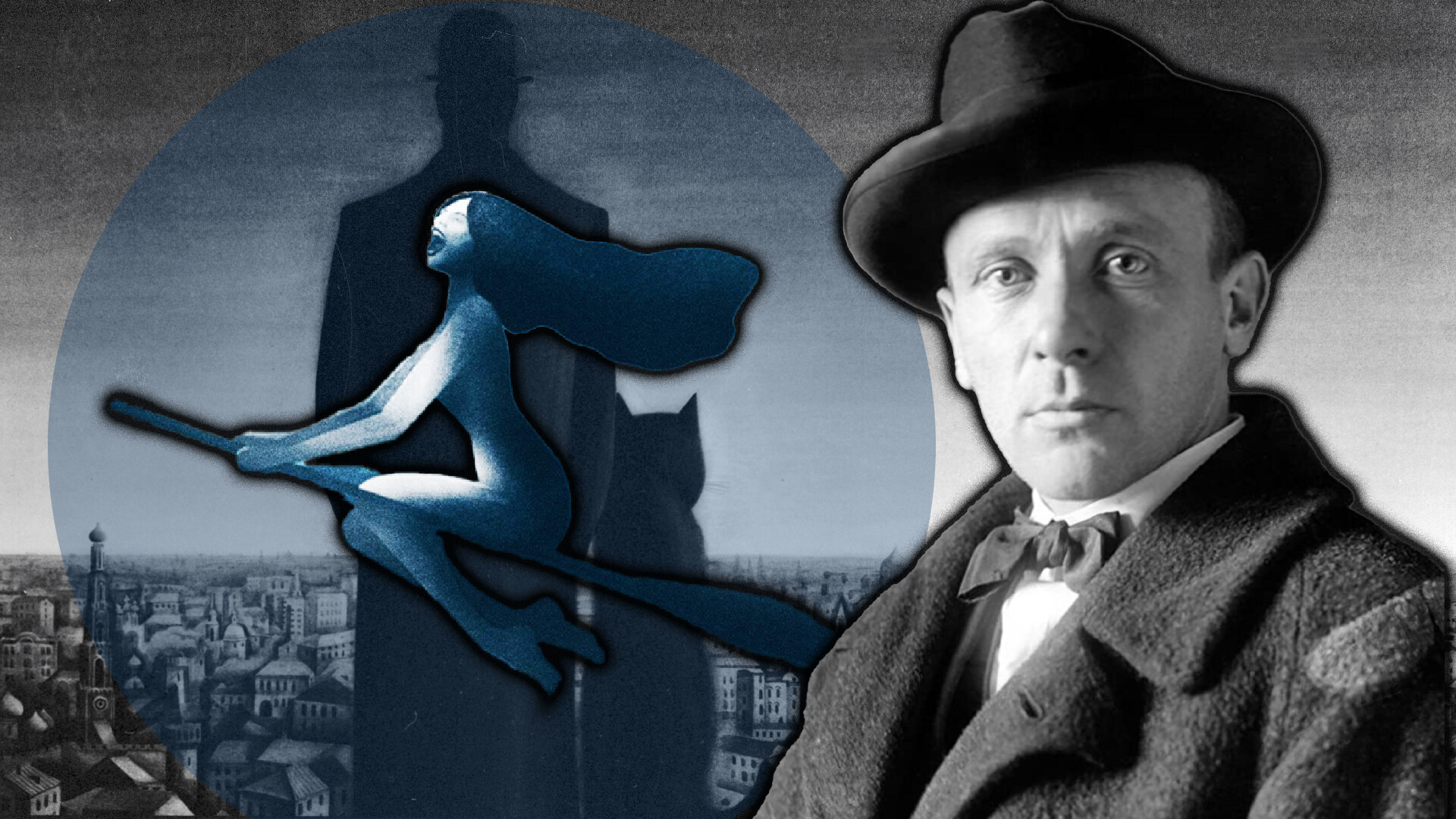

A married woman leaves her well-to-do husband for the man she loves - a poor and hapless writer. To help him write a novel and publish it, she strikes a deal with the devil and becomes a witch.

A still from 'The Master and Margarita series'

A still from 'The Master and Margarita series'

This is the main storyline of Mikhail Bulgakov's most important work, the novel The Master and Margarita, (you can read a short summary of it here). According to literary experts who specialize in Bulgakov’s oeuvre, the novel is strongly autobiographical despite its magical component.

According to Bulgakov expert Marietta Chudakova, the author's last wife, Yelena Sergeyevna, might have been an informant for the NKVD. She left a high-ranking military man for Bulgakov, but she cooperated with certain people in law-enforcement agencies to save Bulgakov from arrest and to arrange for him to be given an opportunity to write. For Bulgakov, the novel was a vindication of his wife and an admission of sorts that she had struck such a deal for his sake, to keep him out of harm's way.

How the son of a Kiev theologian became a doctor

Bulgakov's works pioneered a whole new direction in Russian and world literature, and many experts and average readers tend to agree that there’s no other writer like him. His novels are fantasy, satire and high-quality Russian prose all rolled into one. What is more, all his works are, to one degree or another, autobiographical.

Mikhail Bulgakov in school years

Mikhail Bulgakov in school years

Bulgakov was born in 1891 into the family of a professor at the Kiev Theological Academy (then the Russian Empire). But Mikhail decided not to follow in his father's footsteps and he enrolled at the Medical Faculty of Kiev University. His choice was not accidental. His mother's brother, Nikolai Pokrovsky, was a well-known doctor (and a wealthy man). He was a leading mind in medical science and a true idol for the young Bulgakov.

Pokrovsky was the one who first welcomed his Kiev nephew to Moscow, where Bulgakov would later settle for a long time. He was also the one who would become the prototype for Professor Preobrazhensky, the protagonist of Bulgakov's novella Heart of a Dog.

A still from 'Heart of a Dog'

A still from 'Heart of a Dog'

Pokrovsky was a gynecologist, however, while his literary alter ego, Preobrazhensky, was an experimental surgeon who transplanted a human pituitary gland and human testicles into a dog (the latter then turned into a human).

Country doctor and morphine addict

During World War I, Bulgakov worked as a doctor on the frontlines, but was then sent to work in a small village hospital in the Smolensk Region. Bulgakov described his experiences and some amusing episodes from his medical practice in the short story series, A Young Doctor's Notebook (1925). Still very inexperienced, he had to deal with numerous difficult cases on his own: turning a fetus in the womb, treating an eye tumor in a child, pulling teeth, etc. At times he even had to sneak a glance in a textbook. In 2012, the entire world heard about Bulgakov's Notebook because in a British screen adaption the main role was played by Daniel Radcliffe of Harry Potter fame.

A still from 'A Young Doctor's Notebook'

A still from 'A Young Doctor's Notebook'

The series also includes the plot line of the short story “Morphine”. Strictly speaking, it is not part of the original A Young Doctor's Notebook series, but because of its subject matter it is often included. The story recounts the diary of a country doctor who accidentally becomes a morphine addict. He describes how under the influence of the drug he develops hallucinations, and in this sick state of mind he observes the revolutionary upheavals in the country. Unable to deal with his devastating dependency on morphine, he decides to shoot himself.

A still from 'Morphine' movie

A still from 'Morphine' movie

In real life, Bulgakov also became a morphine addict. One day, when he was still a small town doctor, he was at risk of catching diphtheria after performing an operation. The anti-diphtheria medication he took provoked an acute allergic reaction, which Bulgakov decided to treat with morphine. And that set him on the road to a habit that grew into a full-fledged addiction. In 1918, Bulgakov returned to Kiev, which was engulfed in the Civil War, and there he continued taking the narcotic. His first wife, Tatiana Lappa, helped him overcome his addiction, which inspired his short story on this tortuous period in his life.

Civil War and literary beginnings

In Kiev, Bulgakov opened a private medical practice where he chiefly treated venereal diseases. Chaos and banditry reigned in the city, which was convulsed by revolution and the Civil War. Political power in the city changed hands several times, and the local people often found themselves facing different and unexpected state decrees.

A still from 'The White Guard' series

A still from 'The White Guard' series

Bulgakov described the atmosphere of those events and the life of his family in the novel The White Guard. The educated, well-born Turbin family attempts to maintain their customary way of life as the world crashes around them. White officers are guests in their house, and Turbin himself joins the Civil War on the side of the Whites. Bulgakov's sympathies also lay with the Whites - something he did not subsequently conceal.

At the end of the Civil War, Bulgakov served as a doctor in the Caucasus (which was where he first started to write). He said that his creative impulse had been with him for a long time, and after all the events and upheavals that he had lived through he gave up medicine and devoted himself to writing. Initially, he was published in a local newspaper in Vladikavkaz, and then he realized that he had to go to Moscow.

Mikhail Bulgakov

Mikhail Bulgakov

In 1921, Doctor Pokrovsky, the uncle referred to above, received his Kiev nephew in Moscow. Bulgakov started being published in the capital's newspapers and magazines. He contributed satirical articles, sketches and journalistic reports. He collaborated particularly closely with the railway workers' newspaper Gudok, which had a strong satirical section and which also published Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov, Mikhail Zoshchenko and other major humorists and satirists of the period.

His first novel, The White Guard, was finally published in a literary journal in 1925, as well as his short stories. Bulgakov was summoned for questioning after the draft of his novella Heart of a Dog, a searing satire of the new Soviet system and the New Soviet Man, was discovered in the course of a search of his home.

A still from 'Heart of a Dog'

A still from 'Heart of a Dog'

Miraculously, however, he was not subjected to any penalties and the manuscripts were returned (but the work was only published for the first time in 1987 during the Perestroika period, whereupon a screen version, which became a cult movie, soon appeared.

Playwright and a phone call from Stalin

Bulgakov's real passion was the theater. He wrote the play, The Days of the Turbins, based on the novel The White Guard, for the Moscow Art Theater (MKhAT). It had a very successful run and Stalin himself saw it several times (he even saved it from being banned).

Among other Bulgakov’s works that Stalin liked were the farcical Zoyka's Apartment about Moscow life of the 1920s. The plot involves a private apartment being turned into a house of ill repute under the guise of a sewing workshop. The play Flight had a very successful theatrical run - it describes a final attempt by the Whites to beat back the Reds in the Civil War, and their eventual defeat and evacuation from Russia.

'The Days of the Turbins' in the Moscow Art Theater, 1926

'The Days of the Turbins' in the Moscow Art Theater, 1926

In the 1930s, storm clouds started gathering over Bulgakov. His subtle satire of the Soviet social system began to be seen as corrosive. The consolidation of Stalin's authority and the new order required the utmost clarity and realism from writers, who were expected to reflect the positive features of Soviet power. Bulgakov's plays were banned from practically all theaters.

Bulgakov described the difficult experience of going around different theaters in a bid to get a new play staged in Theatrical Novel (1936), which paints an ironic picture of the Soviet theatrical and literary world of the 1930s. The majority of characters are modeled on real prototypes. The unfinished novel was only published in the 1960s.

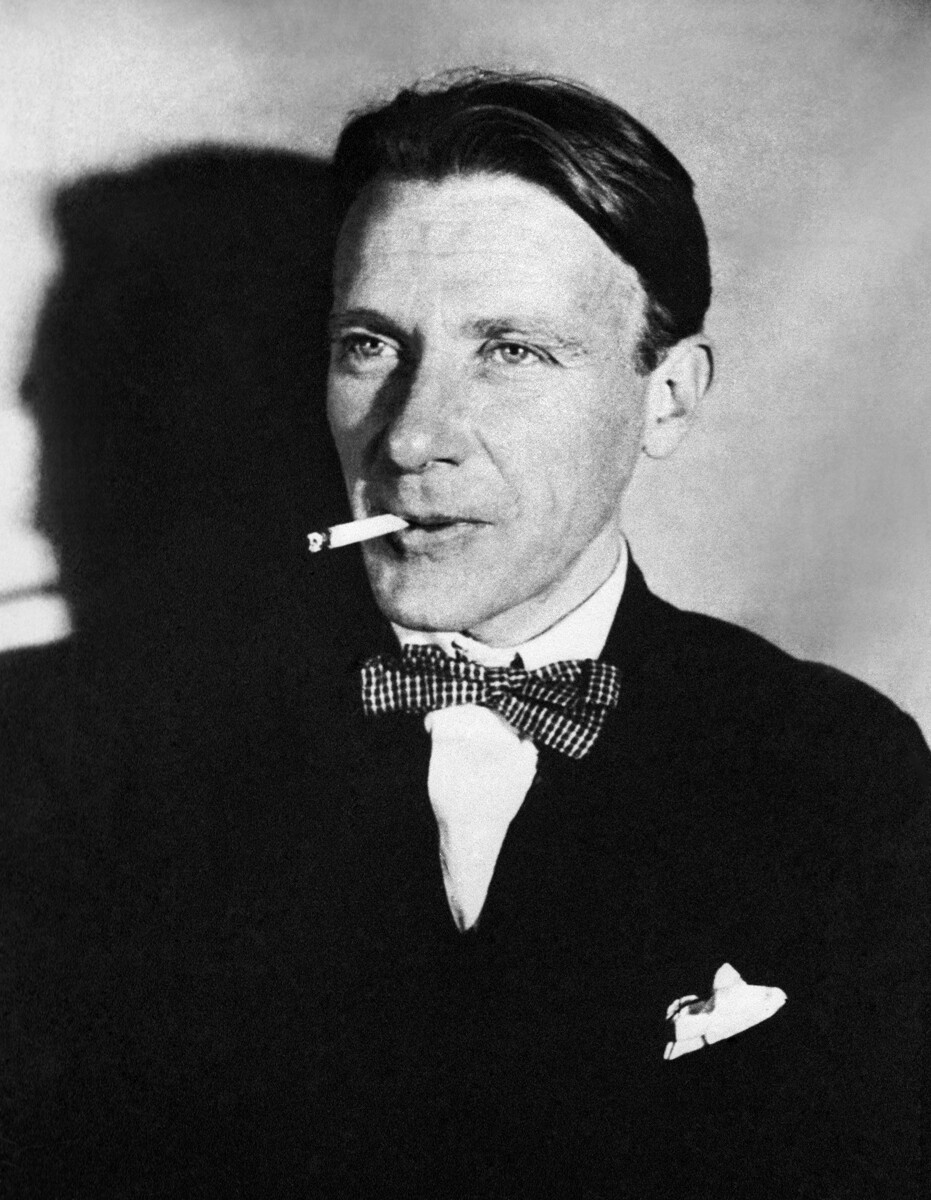

Mikhail Bulgakov

Mikhail Bulgakov

In the 1930s, Bulgakov barely managed to make ends meet: His works weren’t published and his plays weren’t staged. In despair, he even wrote a letter to the government asking either for permission to emigrate or for the opportunity to work in the theater. Soon after, he got a phone call from Stalin himself, who according to the recollection of Bulgakov's wife, posed a trick question: "What, are you really so sick and tired of us?" The question caught Bulgakov off guard, but he replied that a writer could not work so creatively when far from his homeland. Stalin advised him to put in an application for a job at MKhAT: "I think they will agree to take you." Naturally, after that call Bulgakov was given a job, albeit as an assistant stage director, which was a somewhat lowly role for someone of his standing. But the important thing was that he could now work and earn money.

Bulgakov the Master, and his real-life Margarita

Mikhail Bulgakov and his third wife, Yelena Sergeyevna

Mikhail Bulgakov and his third wife, Yelena Sergeyevna

Bulgakov spent more than 10 years writing his novel The Master and Margarita. Work on it proceeded with difficulty, and the writer additionally realized that there was little hope of getting it published. Writing a novel about Christ in the period of atheistic Soviet power was an undertaking doomed to failure from the start. And the novel was first published posthumously more than 20 years after it was written, and with considerable abridgements imposed by the censors.

A still from 'The Master and Margarita' series

A still from 'The Master and Margarita' series

Yelena Sergeyevna, who is regarded as the inspiration for Margarita, did a lot to ensure that the novel was published and that Bulgakov's legacy was preserved. She passed some of his banned works to the West for subsequent publication - to prevent them from falling into oblivion or being destroyed or seized by the KGB.

Today, The Master and Margarita is a massively popular cult novel, known throughout the world. In fact, many Russians love it so much that they can readily quote by heart entire sentences and passages from the famed novel.