There were many legends about Pushkin’s gambling addiction and most of them were true. Despite the fact that, by the standards of his time, Pushkin was very wealthy, his love of gambling left a significant dent in the poet’s budget. He played bridge, faro, ombre and other card games, risking his fortune all the time. Once, he almost lost an as yet unpublished part of ‘Eugene Onegin’, but managed to win it back in the last moment. This is how Anna Kern, one of his many lovers and muses, described his addiction: “Pushkin was very fond of cards and he used to say that they were his only real attachment.”

Sergei Lvovich Pushkin engraved by K. Gampeln

Public domainHis father didn’t approve of Pushkin’s addiction and there were rumors that the poet would be disinherited because of it. Pushkin’s relations with his father were indeed difficult, but disinheritance would have cast a shadow on the entire family and, in actual fact, even huge debts would not have been a good enough reason for such a radical step. Also, there is no documentary evidence to support the idea.

But, he did have many debts: After his death in a duel, it emerged that Pushkin had card debts of almost 150,000 rubles (equivalent to about 240 million rubles today!). Yet, it was not his father who paid them off, but Emperor Nicholas I himself: He cleared the whole amount and, furthermore, supported Pushkin’s family out of the state treasury.

This list is not fiction at all and it was even published in 1887 in ‘Album of the Pushkin Exhibition, 1880’. Starting in 1829, the poet wrote down the names of women he was attracted to or was intimate with in two parallel lists. The lists included 37 names, in total. According to some historians, the poet wrote the names of the women he loved most in the first list, while the second was a list of women he was simply attracted to.

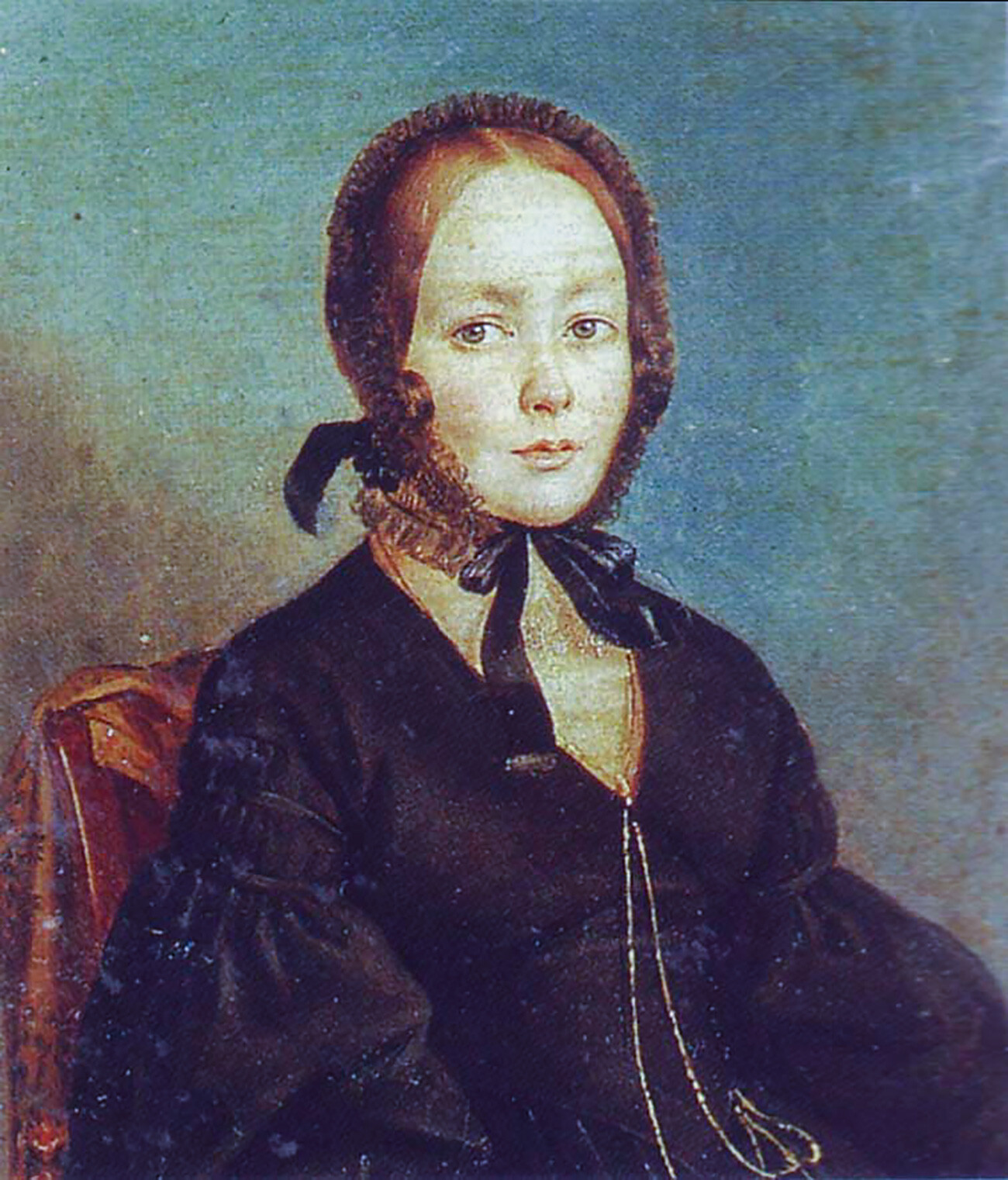

Supposed portrait of Anna Kern

A. Arefov-BagaevHistorians have managed to identify, albeit not entirely accurately, some of the women with whom Pushkin had some attachment. Among them were believed to be Ekaterina Karamzina, wife of the prominent historian Nikolay Karamzin; Anna Petrovna Kern, to whom Pushkin subsequently dedicated one of his best-known poems, ‘I remember that wonderful moment…’; as well as an actress of the Tsarskoye Selo Theater, a lady-in-waiting to the empress, the daughter of a French Duke, the daughter of an Austrian banker, the wife of the governor of Odessa and other prominent “unattached” or married ladies.

Portrait of Natalia Nikolaevna Pushkina-Lanskaya (née Goncharova)

Alexander BryullovSupporters of this theory claim that Pushkin faked his own death and traveled to France where he started writing novels under the name of Alexandre Dumas. It is alleged that two things could have prompted him to do so: gambling debts - which he was unable to pay off to the end of his life - or a decree by Emperor Nicholas I secretly sending Pushkin to France as a “spy” and, in return, paying all the poet’s debts and providing for his family.

Alexandre Dumas in 1855

Public domainYes, on the one hand, Pushkin would have been perfectly capable of playing this “role”: He had a perfect command of the French language and was acquainted with the manners of the higher echelons of society that he was supposed to gain access to - he just needed to create a convincing persona for himself. That, according to the theory, is how Alexandre Dumas appeared on the scene.

Nevertheless, despite the arguments of the adherents of this legend (similarities of appearance, references to Pushkin’s life in the works of Dumas, among others), there are an equivalent number of counter-arguments. For instance, Alexander Dumas was already fairly well known as a writer in the 1830s and many of his plays had already reached Russian theaters by that time. Moreover, the writer took part in the 1830 July Revolution, while, at that time, Pushkin himself was preparing for his marriage to Natalia Goncharova.

After the fateful duel, many of Pushkin’s friends and relatives visited him at home and as many as eight doctors attended Pushkin in his last days, so the chances of everyone who saw Alexander Sergeyevich at that time being persuaded to keep things a secret would have been extremely small.

This was partly true because Pushkin’s great-grandfather, Abram Petrovich Gannibal, was born somewhere in the region of present-day Cameroon (or Ethiopia - there are sharply conflicting accounts of the exact details). In the early 18th century, he was captured and then the merchant Sava Raguzinsky brought Gannibal to Moscow. Within a year, he had been baptized and the godfather was Emperor Peter I himself. In Russia, he was to become the chief military engineer of the Russian army and his son from his second marriage was Ossip Gannibal, the poet’s grandfather.

Portrait, attributed by some researchers as a portrait of A.P. Hannibal

Public domainThis is the only circumstance that justifies the assertion that Alexander Pushkin was an African poet. And, although he really did hark back to his historical roots in his works fairly frequently, in reality, he was just one-eighth African and indeed a further one-eighth German, with the remaining 75 percent of his family tree being purely Russian. Many people still aren’t convinced that the story is true, but there is documentary evidence of the existence of Abram Gannibal, so there is no reason to doubt Pushkin’s partial African ancestry.

There is a myth that if a hare had not run across the path of a carriage Pushin was traveling in from Mikhailovskoe (where he was living in exile) to St. Petersburg, the poet would most likely have been sent to Siberia or executed for involvement in the Decembrist Uprising. And, although he was not regarded as a Decembrist and did not take part in political protests, Pushkin's freedom-loving poetry could have backfired on him, so going to St. Petersburg (particularly when he was supposed to be in exile) was dangerous. A hare crossing one’s path was seen as a very bad omen and the superstitious poet turned the carriage back.

However, as good this legend might sound, in reality, things turn out to be a bit more complicated. The poet’s friend Sergei Sobolevsky wrote that the hare crossed Pushkin’s path not on the way to the capital, but when he went to say goodbye to his neighbors. And that it wasn’t a hare that stopped the poet, but something else considered a bad omen in the 19th century - a priest at the gates of the estate. It was only then that the poet decided to stay.

For all that, the hare has, nevertheless, gained an immortal place in history. In 2000, not far from Mikhailovskoe, a monument was put up to the hare as the poet’s “savior” from an early death. But, as is known, it did not help him for long - Pushkin would still die at the very young age of 37.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox