Boris Grigoriev was born in Moscow, but studied and began his career at the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. One of the prominent collectors in the capital at the time was Alexander Korovin, the owner of textile stores and an art connoisseur with good taste. He was one of the first to start buying Grigoriev's works; he took painting lessons from him and the two became friends. A prominent place in Korovin's esthetically artistic house was assigned to a vibrant portrait of Vsevolod Meyerhold painted by Grigoriev. This panel from the Tretyakov Gallery, which has the collector's name in its provenance, is most likely to have been on display in his house, too.

Grigoriev began traveling abroad while still a student. First, he visited his mother's relatives in Sweden (he was the illegitimate child of Clara von Lindenberg and banker Dmitry Grigoriev and was adopted by his father's family at the age of four). In 1913, the aspiring artist went to Paris where, for four months, he studied at the private Académie de la Grande Chaumière, soaking up impressions and making preparatory studies for a competition painting at the Academy of Arts. Several series depicting scenes from the daily life of Parisian singers, dancers, circus performers and prostitutes were also begun there. All of them were, later, included in the 'Intimacy' (Intimité) series and a book of the same name published in 1918. The painting 'The Street of Blondes', depicting a Parisian woman of easy virtue, was the first double page spread in the book.

In the years 1916-1918, on the eve and in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution, which divided the lives of many (including Grigoriev himself and the publisher Alexander Burtsev who had given him his first commissions) into "pre-" and "post-", the artist worked on paintings and drawings in the 'Raseya' ('Russia') series. The works were shown at exhibitions in Petrograd and Moscow and were published in an album of the same name that came out in 1918. The protagonists of the series are the inhabitants of villages in the northern part of Russia, but the authorities disliked the way he had interpreted and represented them to such an extent that the album was banned right up to the collapse of the USSR. Grigoriev left the country along with his family in 1919 and finished work on the series in exile abroad, where another, expanded, version of the 'Raseya' album was published. The series itself was to be one of the key works in the master's creative output.

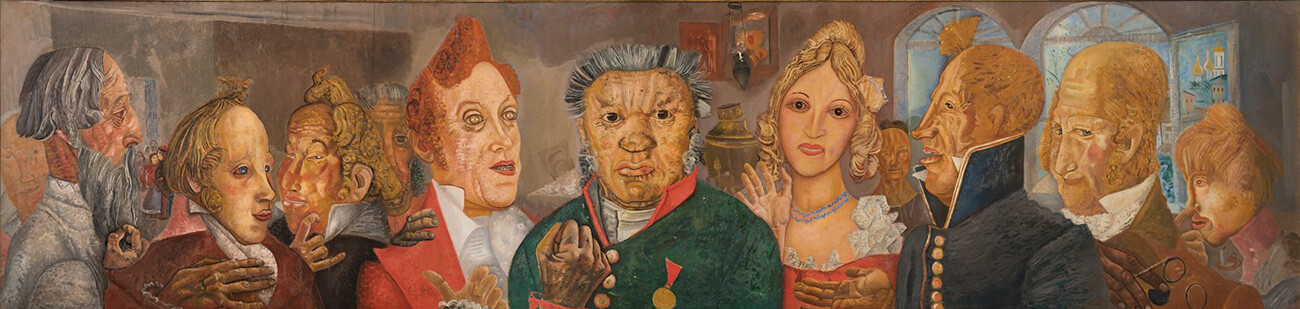

Abroad, Grigoryev did quite well for himself – none of his fellow countrymen was, perhaps, as popular and exhibited as frequently. He wrote: "I am the world's number one master now. I make no apology for these phrases. You have to know who you are, otherwise you won't know how to act." The enormous 'Faces of Russia' canvas was painted at the time he moved from Berlin to Paris and held such significance for him personally that he never parted with it, except for exhibitions in Paris and New York.

Many of the prominent figures of Russian culture of the early 20th century aspired to pose for Grigoriev. He created a substantial gallery of portraits of celebrated contemporaries. The poets Sergei Yesenin and Velimir Khlebnikov, artists Ilya Repin and Nicholas Roerich, theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold and opera singer Feodor Chaliapin are just a small sample of his sitters. Grigoriev worked painstakingly, sketching the face, movements and color from life. The portraits were then completed without the presence of the sitters – "An impression (and hence receptiveness on its own) can do more than working from life," he explained. In the portrait of Gorky, the artist set the writer, who posed for him on Capri, among the characters of his play 'The Lower Depths', which he had seen several years earlier when the Moscow Art Theater had been on tour in Paris.

Grigoriev prospered to such an extent that he could afford a house on the Côte d'Azur. The villa was called ‘Borisella’, combining the names of its two owners – Boris and his wife, Ella. He didn't move in straight away: In 1928, the artist was offered a professorship at the Academy of Painting in Santiago, Chile.

He did not refuse and, although a career there did not work out, Grigoriev managed to hold an exhibition in Argentina and to travel around Latin America, painting a number of works drawn from his travels. He was there again in the late 1930s, arriving from the U.S.

The 'The Government Inspector' canvas, like the series of illustrations for Dostoevsky's 'The Brothers Karamazov', is one of the works that the Russian public had never seen before. They were acquired at auctions in the West by Viktor Vekselberg for his Link of Times Foundation. This late work, made not long before the artist's death, is a sort of summation of his creative career in the art of printed illustration that began in his student years when he illustrated the Russian classics for the publisher Alexander Burtsev. The painting was part of the 'Faces of Russia' series, which was a sort of continuation of 'Raseya'.

A retrospective exhibition of the work of Boris Grigoriev, 'The World's Number One Master', has opened in the new wing of the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg and is to run until Jan. 28, 2024.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox