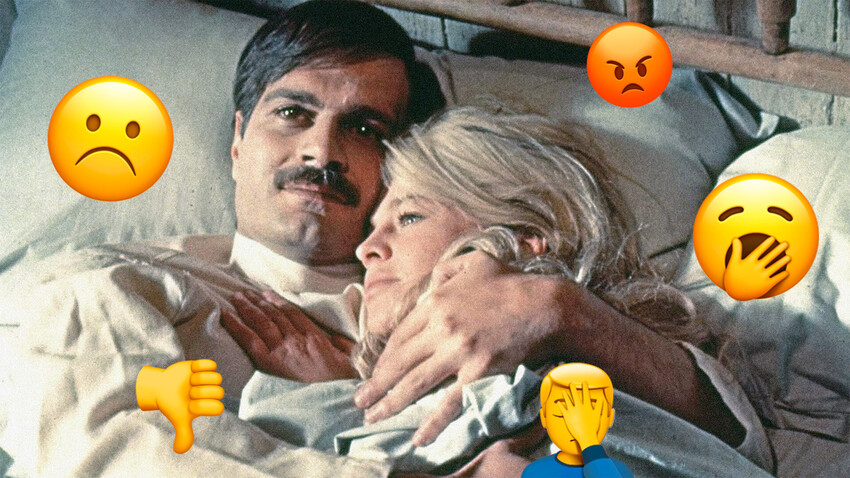

A still from ‘Doctor Zhivago’ movie

David Lean/Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Carlo Ponti Production, Sostar S.A., 1965

A still from 'A Pistol Shot' movie, based on one of Pushkin's 'Belkin Tales'

Naum Trakhtenberg/Mosfilm, 1966Pushkin, who was, first of all, famous as a poet, wrote several prose works that joined the golden fund of Russian classics. Soviet literary studies praised the realistic ‘The Belkin Tales’, created as though from the perspective of a storyteller, whose notes Pushkin simply chanced upon. However, contemporaries didn’t appreciate Pushkin’s prose.

Although critics noted his “smooth” style, they criticized the absence of an idea. Separate stories they called anecdotes, quite overdrawn at that. “‘The Belkin Tales’ are easy to read, for they don’t encourage one to think,” St. Petersburg newspaper ‘Severnaya Pchela’ (‘Northern Bee’) wrote. “These are farces, crammed into a corset of simplicity, without remorse,” the magazine ‘Moskovsky Telegraph’ (‘Moscow Telegraph’) responded.

Vissarion Belinsky,the near-leading critic of the 19th century, wrote about the fact that ‘The Belkin Tales’ received a cold welcome from the public and print media. In his series of articles about Pushkin, he mainly praised and admired his talents, but noted: “Although it can’t be said that they had nothing good in them at all, these stories, after all, were unworthy of the talent or the name of Pushkin. <…> One of them is particularly pathetic – ‘The Noblewoman-Peasant’ – unrealistic, vaudevillian, presenting a landowner’s life from an idyllic point of view…”

According to some researchers, all the stories were written by Pushkin as parodies in the genre of everyday anecdotes, with an unexpected conclusion. But, alas, even if it was humor, contemporaries didn’t understand it.

Later, in the 1860s, critics reconsidered their view of the stories and, first of all, of the storyteller Belkin and praised him as a modest bearer of the Russian character, meek and humble. Dostoevsky wrote that everything truly beautiful that our literature has to offer, “all of it was taken out of the people, starting with the humble, naive type of Belkin”.

A still from ‘The Government Inspector’ movie

Vladimir Petrov/Mosfilm, 1952Gogol read his comedy for the first time in 1836 in the house of poet Vasily Zhukovsky, where the entire literary beau monde had assembled. Many laughed out loud, Pushkin also “rolled around laughing” (who clued the author the plot set-up). But, there were also those who immediately accused the play of being a “farce, offensive to the art of writing”. Some called this comedy rude and plain. There were those who scolded Gogol for being unrealistic – allegedly, the character of the mayor could not have mistaken a simple adventurer for a government inspector. “There was also no need to slander Russia,” conservative critic Faddey Bulgarin wrote, thrashing Gogol for a lack of positive characters.

By accident, Emperor Nicholas I allowed the comedy about corrupt provincial state officials to be published and to be staged at theaters: he failed to notice the metaphor of the entire Russia in the play. But, at the premiere, he was laughing and then said: “What a play! Everyone got rinsed, and I more than anyone else!”

Its success in theaters was colossal, but Gogol himself believed it to be a flop – he fancied that the actors didn’t get the plot and didn’t perform it well. Out of desperation, he even went to live overseas for some time.

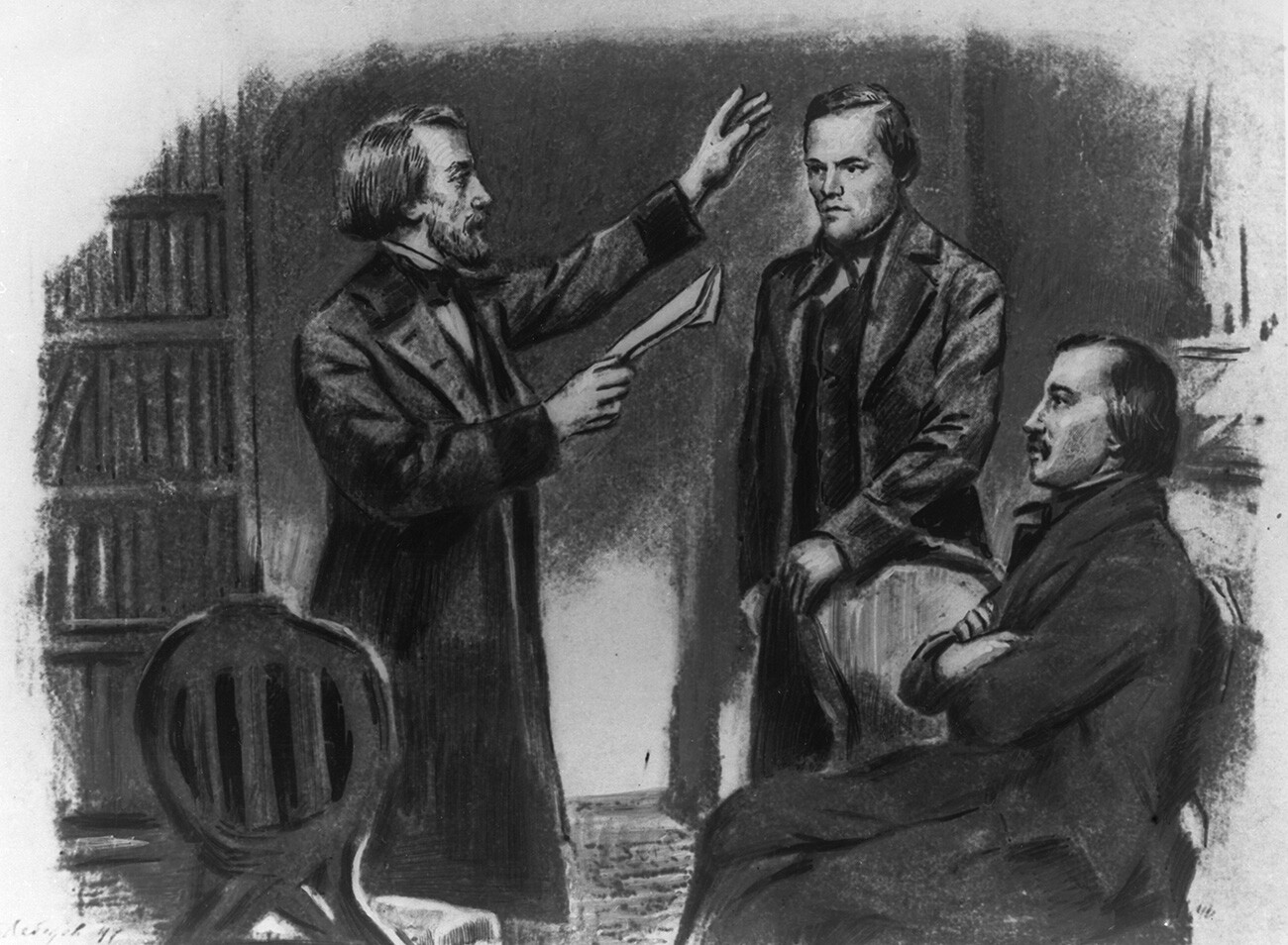

Critic Vissarion Belinsky reads ‘Poor Folk’. Reproduction of a Soviet drawing, 1948

TASSThis was one of the first psychological works of Russian literature about an unremarkable small-time, modest government official. Having read the manuscript, critic Belinsky was amazed and dubbed the author the “new Gogol”. Even before the work was published, he spread the news around the entire St. Petersburg about a new talented writer. This caused a two-fold reaction to the novel. On the one hand, his high praise was a ticket to the world of literature for Dostoevsky. On the other hand, many critics treated the work with apprehension and even skepticism. Some even accused Dostoevsky that Belinsky had too much influence on him.

In a way, it was true: Under the influence of Belinsky, the thankful young author joined the ranks of the revolutionary-minded Petrashevsky Circle. To them, he later read Belinsky’s banned letter to Gogol, in which he criticized Russia – for this, Dostoevsky was nearly executed, with his sentence to be hanged replaced at the last moment by hard labor.

‘Poor Folk’ was criticized for a lack of form and unclear substance: “Out of nothing, he fancied to build a poem, a drama and nothing came out as a result, despite all the pretension to create something deep,” newspaper ‘Severnaya Pchela’ wrote. Many criticized the lengthiness of the story and excessive exhausting details (Belinsky himself later admitted that the novel was too wordy).

Critic Apollon Grigoryev called the sentimentality of the author false; he didn’t believe that Dostoevsky truthfully “praised” such small people as his character. Some accused Dostoevsky of mimicking Gogol and his ‘Petersburg Stories’. By the way, Gogol himself read the novel and praised the writer’s talent; however, he noted that the author was still young and agreed that he was prone to wordiness: “Everything would seem much livelier and stronger if it was more concise.”

A still from ‘Doctor Zhivago’ movie starring Omar Sharif as Yury Zhivago

David Lean/Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Carlo Ponti Production, Sostar S.A., 1965Today, his novel about the Russian Civil War is considered one of the best works of Russian literature of the 20th century. For it, Pasternak was awarded a Nobel Prize for literature. However, in the USSR, he was not only barred from publishing until perestroika; the author was truly prosecuted.

The editorial board of the ‘Novy Mir’ (‘New World’) magazine, where new books were published, stated in an open letter that this book depicted the October Revolution in a slanderous way, as well as the people, “who carried out this Revolution and the construction of Socialism in the Soviet Union”. The Nobel Prize award was called a political campaign. According to “truly Soviet” editors, the prize was connected with the “anti-Soviet buzz around the novel”, which in no way reflected the ‘literary qualities of the works of Pasternak.’

Read more: What’s behind the Soviet phrase ‘Didn’t read Pasternak, but condemn him’

A still from ‘Lolita’ by Stanley Kubrick

A.A. Productions Ltd., Anya, Harris-Kubrick Productions, Transworld Pictures, 1961In the puritanical U.S., such an “erotic novel” was refused from publication by four publishing houses.

Many feared unpleasant consequences for their reputation and even possible judicial proceedings. With that, polite refusals to the author were accompanied by quite positive reviews. Only in France did they dare to publish the novel; the head of the publishing house admired how the author had “managed to carry the Russian literary tradition over into the modern English prose”.

The book had all the chances to be left unnoticed, but a polemic scandal rose around it in the British press. From the pages of ‘The Times’ newspaper, Graham Greene recommended ‘Lolita’ as one of the best books of 1955, while John Gordon, editor of the ‘Sunday Express’ newspaper, retaliated to his colleague by calling it a “dirty little book” and “undisguised pornography”.

In many countries, the novel about the relationship of an adult man with an underage girl was banned for a long time. The distribution of the book, where pedophilia was depicted so aesthetically (and almost justified), was considered harmful and even dangerous. In France, it was also banned after its first publication, but, later, the publishing house regained its right to publication through the court system.

In the USSR, naturally, the book was also banned. Nabokov himself ironically said that it was hard for him to imagine what kind of regime and censure in “my prissy Fatherland” would allow the novel to be published.

However, it was actively distributed through self-publishing – famous poets Andrey Voznesensky and Yevgeny Yevtushenko had allusions of ‘Lolita’. The novel wasn’t published not only because of “perversion”, but also because of the personality of the author himself. The Soviet press criticized Nabokov for “a text full of snobbery and designed for a curious bourgeois”. In 1970, an article was released in ‘Literaturnaya Gazeta’ (‘Literary Gazette’), which called ‘Lolita’ a product of an emigrant who had betrayed and sold his homeland. Many furious letters arrived to the newspaper’s editorial team from the people who had read this “little novel of White emigrant Nabokov” and demanded him to be put on the international wanted list.

In 1989, ‘Lolita’ was published in the USSR, again causing a real splash.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox