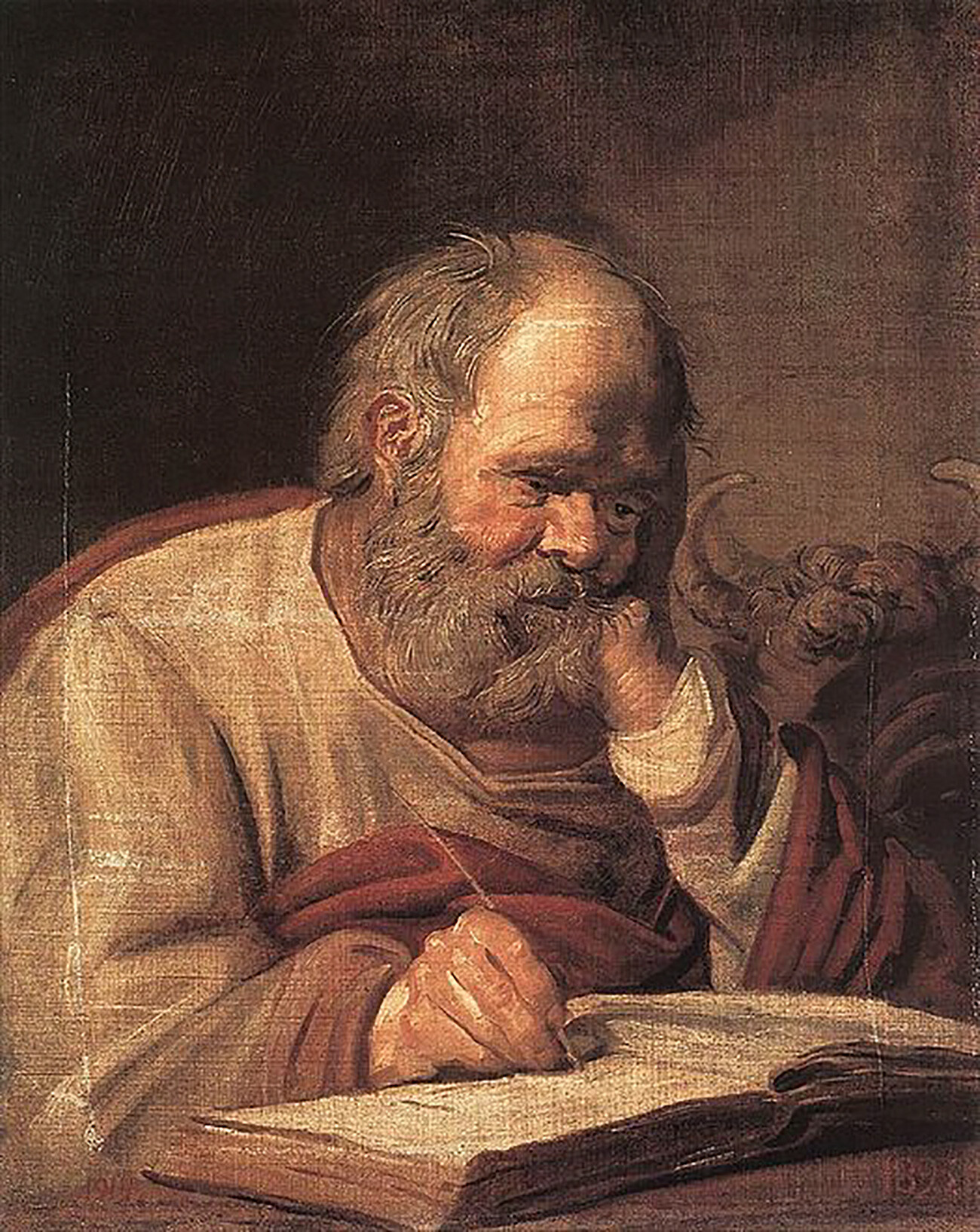

Frans Hals

Museum of Western and Eastern ArtThe theft in 1965 of a masterpiece by 17th century Dutch painter Frans Hals from Moscow’s Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts was so outrageous that even a film was made about it - “The Return of Saint Luke” (1970). Two of Hals’ paintings from his series of portraits of the Evangelists that were painted in the 1620s – “St. Luke” and “St. Matthew” – were brought to Moscow from the Odessa Museum of Western and Eastern Art. On a day when the Pushkin Art Museum was closed and being cleaned, a thief cut one of the paintings out of its frame. Only a day later was the painting discovered missing. A lucky break, however, helped recover the masterpiece. Half a year after the disappearance of “St. Luke”, a man approached another well-dressed man near a shop on Arbat Street, in the very center of Moscow. He offered to purchase an Old Master painting for 100,000 rubles. The well-dressed man happened to be a KGB agent, and he immediately caught wind of something fishy. As a result, the thief was apprehended – it was a man by the name of Valery Volkov, a Pushkin State Museum employee. He had been employed as an assistant to a wood restorer. Volkov didn’t have a university degree, so he hatched a plan to buy a degree in exchange for the painting. The deal fell through, however, and the thief decided to sell the Hals masterpiece but ended up getting caught.

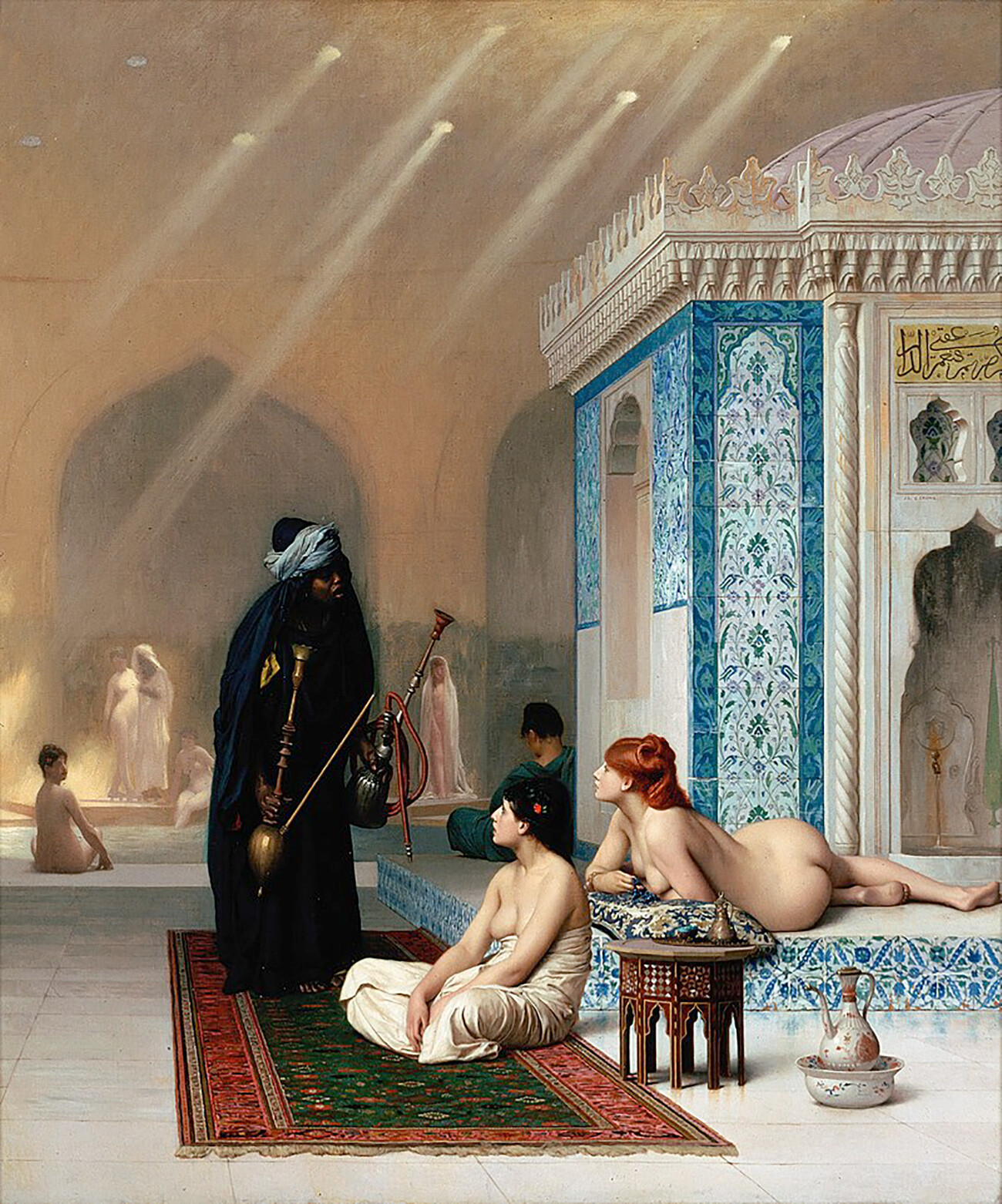

Jean-Léon Gérôme “Pool in a Harem” (c. 1876)

Public domainThe intense desire to pilfer a museum masterpiece is sometimes so great that thieves don’t even bother to use stealth when they commit their crime. That’s what happened to Jean-Léon Gérôme’s painting “Pool in a Harem” (c. 1876) that was stolen from the State Hermitage Museum in 2001. The thieves exploited the fact that the hall with the artist’s paintings had been closed to visitors, and so they simply stepped over the roped barrier. The rest was simple: the painting was cut from its frame with a knife and spirited out of the Hermitage. Since this was well before CCTV became ubiquitous, the thieves disappeared without a trace. In 2006, however, the painting was left in the reception area of the Communist Party’s office in Moscow. The years away from the museum had left their mark, however. The “Pool” had been damaged, and so it was immediately sent to experts for restoration. Three years later, it was returned to the exhibition halls of the Hermitage Museum.

Jewelry, religious icons, items with gems– overall, more than 200 museum items worth 150 million rubles disappeared from the State Hermitage Museum’s collection over the course of many years. But only in 2006 were they discovered missing. A museum employee, Larisa Zavadskaya, and members of her family fell under suspicion. It turned out that over the course of many years the perpetrators had been carefully replacing the genuine items with less valuable ones, selling the originals on the black market through their accomplices. Thanks to making the issue public, local collectors came forward with stolen items that they had inadvertently purchased, and 34 items in total were eventually returned to the Hermitage. But a significant portion of what had been stolen remained lost.

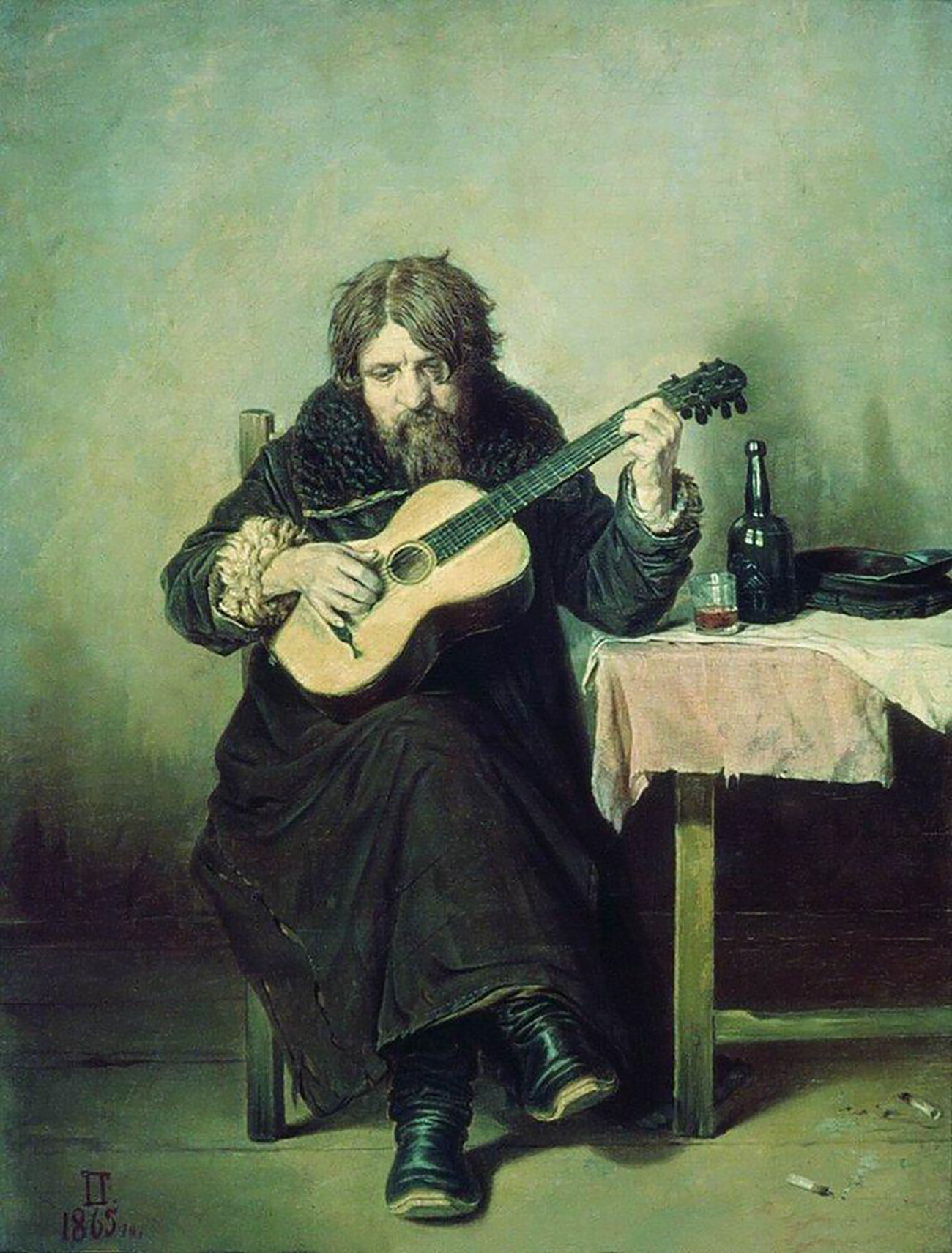

Vasily Perov “Solitary Guitarist”, 1865

Public domainOn a spring night in 1999 two criminals broke a window on the first floor of the State Russian Museum and stole Vasily Perov’s painting “Solitary Guitarist” (1865), as well as his study for the painting “Troika”. Having heard the alarm go off, the guards set off in pursuit of the thieves, who nevertheless managed to escape. In the end, however, they were caught, and the paintings were discovered in a luggage room at the Warsaw Station in central St. Petersburg.

A mad desire to possess gold seized the mind of a thief who decided to rob a local history museum in Rostov-on-Don in 1971. Having sneaked into the building through a window, he broke the display case and snatched some gold phaleras (a type of crafted disk) that had been used to adorn horse harnesses and which had been found in a Sarmatian chieftain’s burial mound. The criminal had no particular fondness for ancient history; rather, he just wanted to sell the precious metal and get the cash. Unfortunately, the thief managed to melt down the phaleras, and the museum lost these precious items forever.

Arkhip Kuindzhi “Ai-Petri. Crimea”

State Russian MuseumOn January 27, 2019, directly in the gallery filled with visitors, a thief snatched Arkhip Kuindzhi’s painting “Ai-Petri. Crimea” out of its frame and walked away. The museum visitors who were present had thought that a worker of the State Tretyakov Gallery had taken the painting for some official business. Only an hour and a half later did the museum realize what really had happened and they raised the alarm. The thief was apprehended quickly; and the painting was found stashed at a construction site in the Moscow Region’s town of Odintsovo.

Titian “Esse Homo” (c.1570)

The Pushkin MuseumRembrandt, Titian, Correggio, Pisano, and Dolci – on the morning of April 25, 1927 employees of the Pushkin Museum arrived at work only to discover that paintings by these Old Masters had gone missing. On Easter night, when the church bells were ringing, the perpetrator smashed out the window and stole the masterpieces. When the police arrived on the scene they were astounded because the glass shards had been cleaned up along with all potential clues; also, a note that the criminal had left behind had been touched by several people. The only painting that was quickly discovered was “Flagellation of Christ” (c. 1320) by Giunta Pisano. In autumn 1931, the police got a lead on a certain “Fedorovich”, an employee of the People's Commissariat for Posts and Telegraphs. In the past, he had been a gang member who robbed museums in St. Petersburg. During questioning, he denied everything, but in the end his friend ratted him out. As it turned out, Fedorovich had wanted to rob the museum back in 1924. Meanwhile, the masterpieces had spent a lot of time underground in crates and were severely damaged. The painting by Titian, “Esse Homo” (c.1570) – suffered the most because the perpetrator wrapped Rembrandt’s “Christ” in it.

Investigators had long known that something strange was going on with the works of avant-garde artist Pavel Filonov that were stored in the collection of the State Russian Museum. In the 1980s, the works of the reclusive painter were suddenly appearing in the collection of Centre Pompidou in Paris, despite the fact that the painter never sold any of his art works, neither in Russia nor overseas. Moreover, Filonov’s artworks had been a part of his own collection that was gifted to the Russian Museum in 1977 by the artist’s sister, Yekaterina Glebova. Eventually it was discovered that the Russian Museum had only copies, as the originals had been switched by someone inside the museum. New doubts about the authenticity of Filonov’s works emerged in 1992 when a drawing by the artist, which officially was listed in the collection of the Russian Museum, came to the attention of a Russian Museum employee when she was visiting France. Once again, sure enough, a copy was discovered in the Russian Museum. In the end, the investigation managed to solve both of these thefts and bring to light the criminal group that was taking originals from the museum and using them to create copies that were then switched with the originals. In 2000, seven valuable drawings by the artist were returned to St. Petersburg from Paris.

Ilya Repin

Museum of the Russian Academy of ArtsThe search for 16 paintings that were stolen from the Museum of the Russian Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg in December 1999 lasted for several days. Although an alarm went off on the night of the theft, the police arrived to find nothing suspicious – all the locks were in place and windows were intact. The thieves planned everything thoroughly and hid in one of the Academy rooms and waited. Then, they picked the lock on the museum door and cut the paintings from their frames. (The museum is located inside the Academy). Paintings by Repin, Kramskoy, Chrucki, Malyavin, and Tropinin went missing – the stolen items were worth more than a million dollars. Thankfully, the paintings were recovered very quickly.

Isaac Levitan

The Plyos State Historical, Architectural and Art Museum EstateSometimes, museum robberies are reminiscent of third-rate action movies. For example, in 2013, in order to steal Vyacheslav Bychkov’s painting “Market”, thieves cut through the ceiling of the art and historical museum in the town of Kineshma (Ivanovo Region). In 2013, in the town of Vyazniki (Vladimir Region), three thieves first hid in a room of the art and history museum, and then, concealing their faces behind masks, they tied up the guard and stole Shishkin’s “Forest, Spruces” (1897), Korovin’s “Fisher” (1913); and Zhukovsky’s “First Snow.” (1910) In total, the stolen items were worth three million dollars. In 2014, the State Historical, Architectural and Art Museum Estate in the town of Plyos (Ivanovo Region) was hit by thieves who probably saw too many Hollywood films – They spray-painted security cameras and then broke the armored glass with sledgehammers to steal five paintings by Isaac Levitan. Several years later they were recovered during a police raid in Nizhny Novgorod. Eventually, it became clear that the thefts in Kineshma, Vyazniki, and Plyos were committed by the same gang.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox