The nomadic peoples inhabited the vast steppe expanses of Northern Eurasia (and the Russian Empire) for centuries. And, obviously, their lifestyle and culture have been reflected in Russian culture and art. It was the nomads who invented wool and felt, were the first to domesticate the horse and to use fermented milk products – and accustomed Russians to all of this.

Russia adopted a lot from the Mongols and traces of different nomadic peoples have been found in the south of Russia, at the mouth of the Don River. Naturally, the life of nomads in all its forms has been attracting artists and expeditioners for many centuries.

Colonel Dmitry Zatsepin spent more than 20 years in Turkestan, a big Central Asian region which became part of the Russian Empire back in the 19th century. Zatsepin researched the local life and culture and compiled an ethnographic album of several hundred sketches of life in the region. The Syr Darya Region is currently the territory of Uzbekistan.

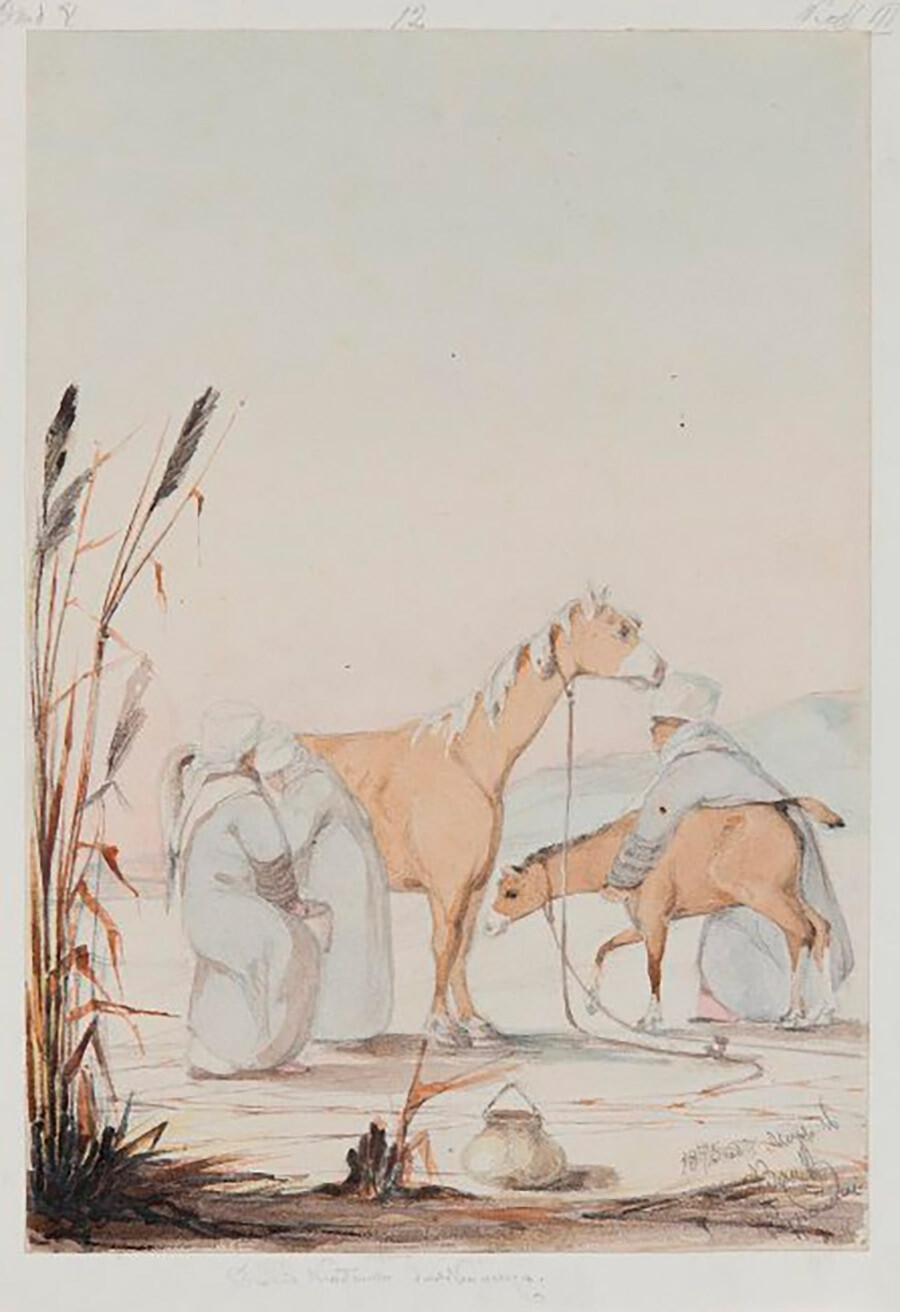

The nomads of Central Asia were among the first people to domesticate horses. And it was they who invented the idea of making a low-alcoholic fermented milk drink called ‘koumiss’ from a mare's milk.

In 1940, artist Vladimir Favorsky made illustrations for the Russian translation of the ‘Dzhangar’ book, a Kalmyk folk epic. The drawing depicts Mingyan, one of the heroes. He was, to use the modern language, a real sex symbol. Take a look at how the girls in the background are dancing and how all their eyes are fixed only on him. “Women can not see him indifferently, their belts untie themselves and the buttons on the chest of the girls all bounce,” the artist wrote about the hero.

Avant-garde artist Goncharova repeatedly turned to Scythian idol babas. Using images of primitive ancient sculptures, she oftenly narrated biblical stories. The basis of her painting ‘Salt Pillars’ was the legend of Lot, the only one who survived when God destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah. In the story, Lot's wife took a glimpse back on the burning cities and turned into a pillar of salt. But Goncharova turns all the heroes into idols, frozen against the background of the flaming ruins of Sodom and Gomorrah.

“I have comprehended everything that the West could give me up to the present time… and, now, my path goes to the source of all art – to the East,” the artist says.

Symbolist Kuznetsov is often dubbed the “songbird of the East”. And his most famous works, created in the 1910s, are devoted to Central Asia, the magic of the steppe and the optical illusions that sometimes happen there.

In 1872, Orenburg photographer Mikhail Bukar presented future Emperor Alexander III with an album entitled ‘Photographic Images of Types of Orenburg Region’. It contained photos of different peoples (Bashkirs, Kirghiz, Kalmyks, Tatars) and their way of life. The photo was colored with watercolors for a more true-to-life look.

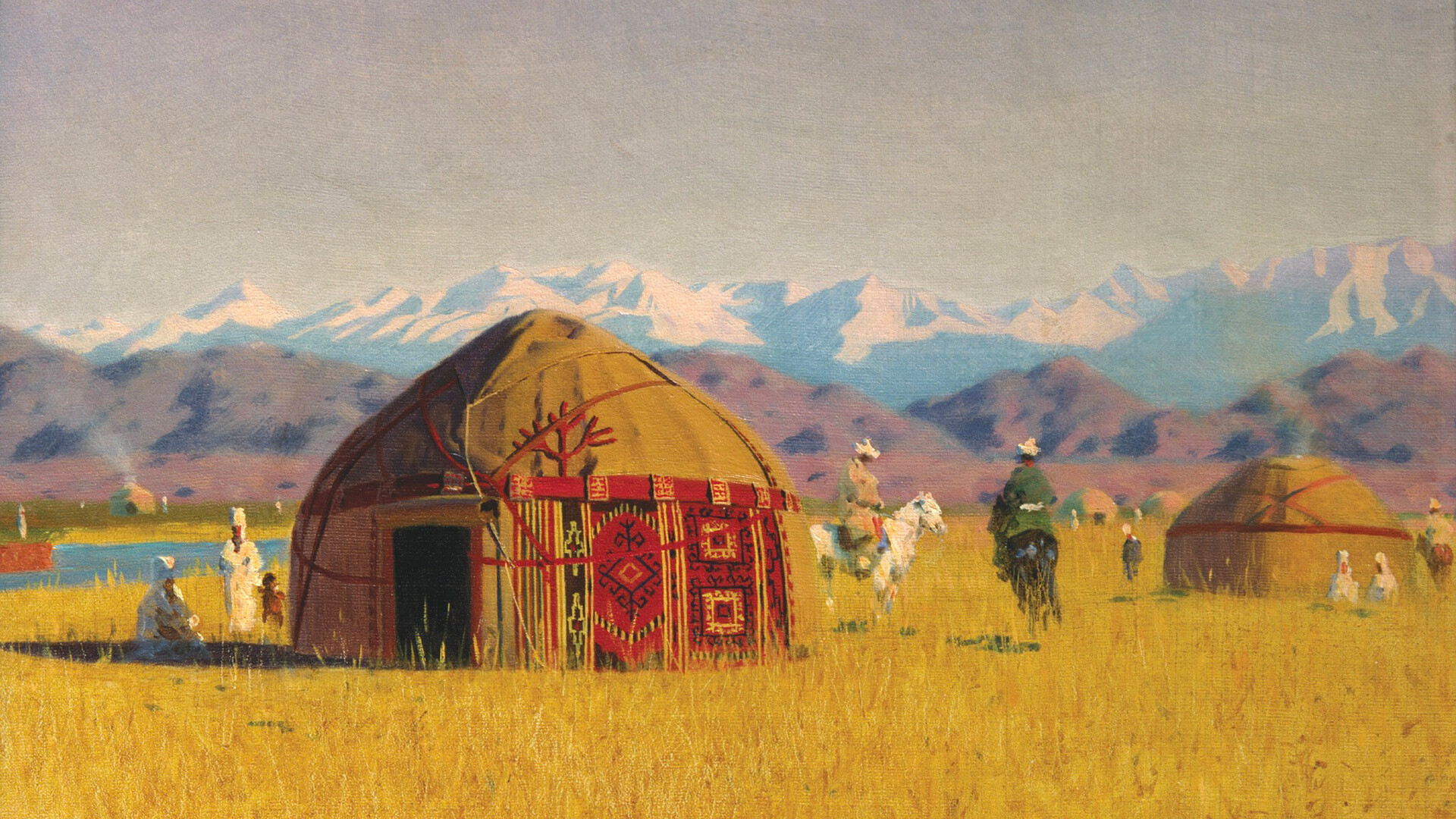

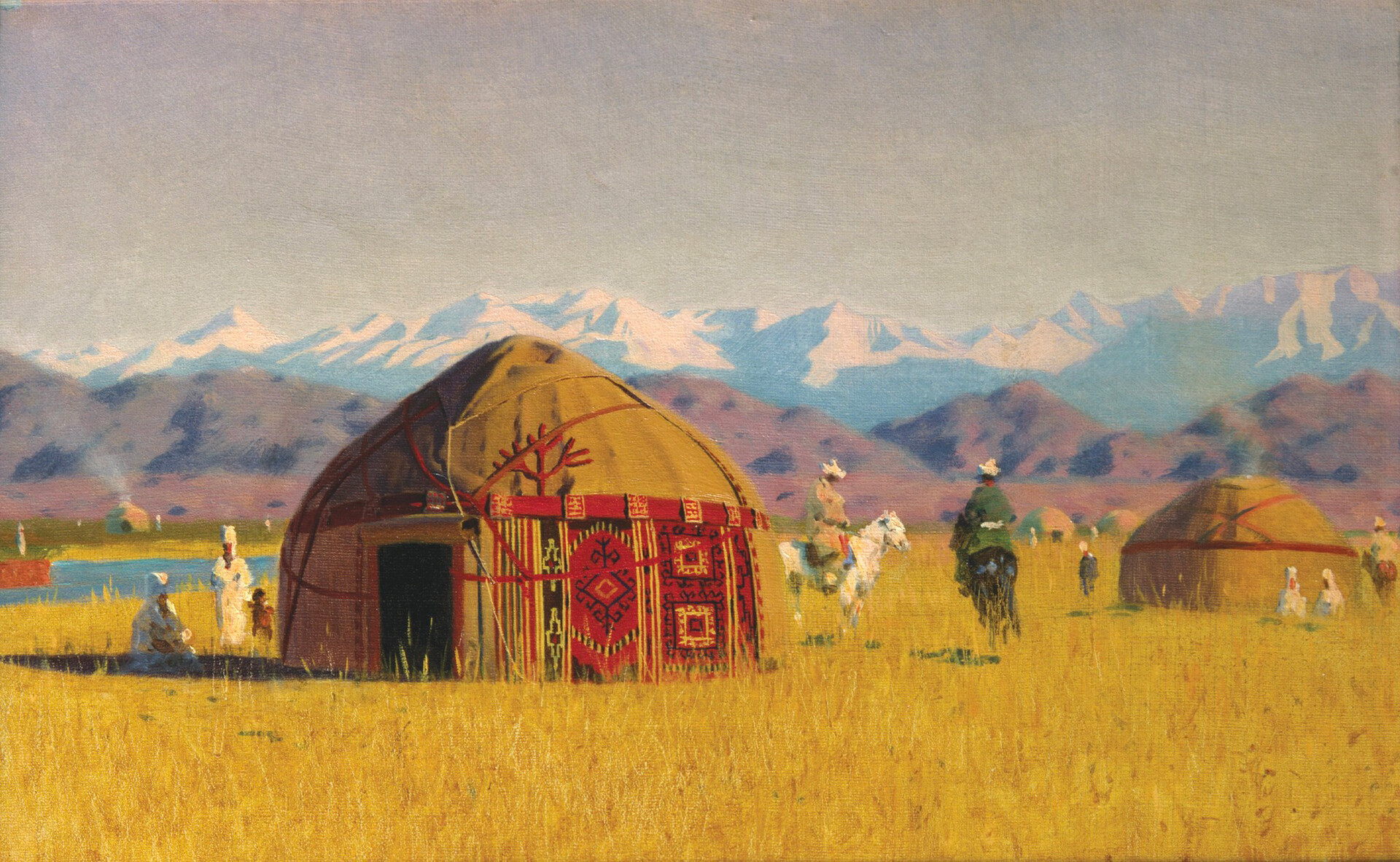

Vereshchagin is known for his battle scene paintings and for his 'Turkestan cycle', where he reflected with documentary accuracy the typical life of the peoples of Central Asia. However, modern experts claim that the artist made a mistake in this picture. In the yurt, traditionally the right half of the door belonged to the male; however, Vereshchagin depicted a woman with a child there, instead.

Nomads with herds of camels, sheep and horses would travel north in spring and summer and return south in fall. During these journeys, they would make long stops by bodies of water, where they would put up their yurts. Setting up these temporary homes was usually a women's job (which, with all its complexity, took only about 4 hours). First, a door was put up, a frame of wooden lattices was installed around it and the structure was covered with felt and woolen fabrics on top.

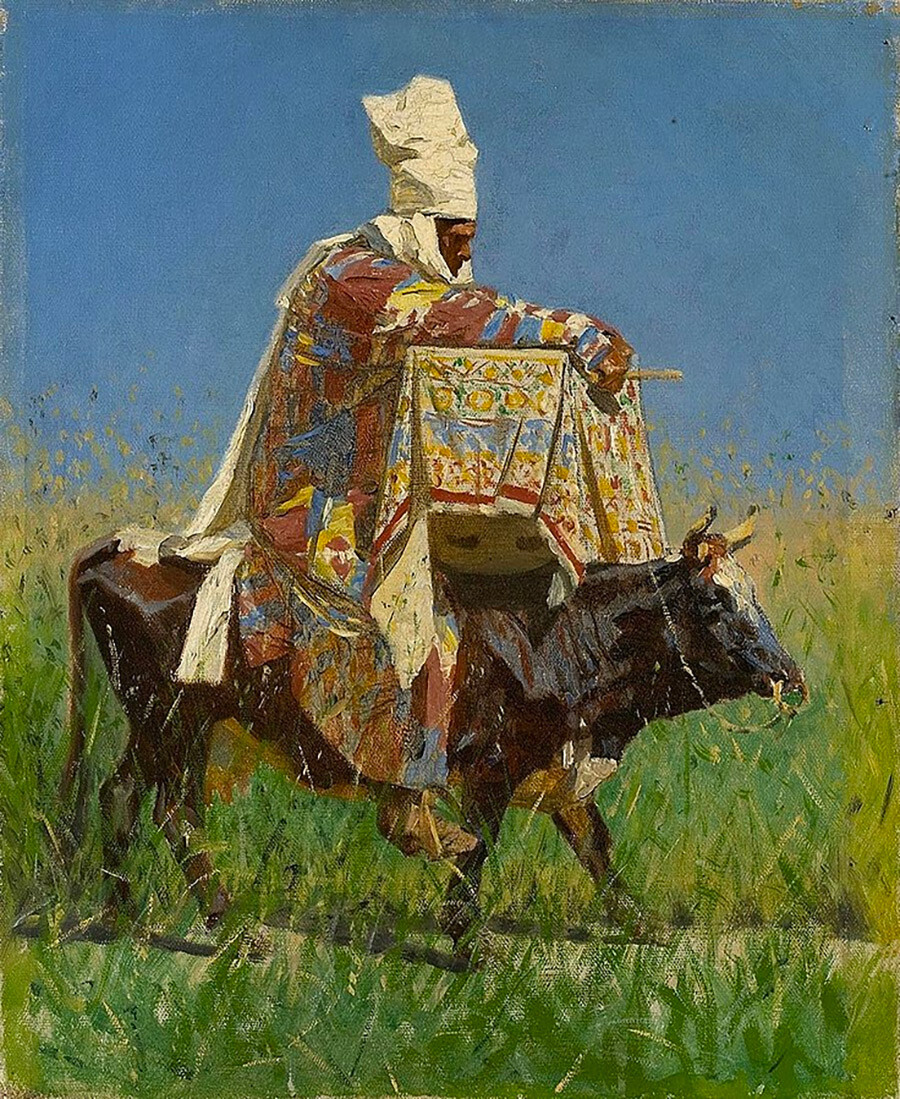

According to one version, in this sketch, a woman is holding a cradle with a child. Vereshchagin accurately depicted the complex pattern of her robe. By the way, the nomads' cows were primarily transportation and were used as draught cattle. For some reason, they preferred to drink sheep's milk.

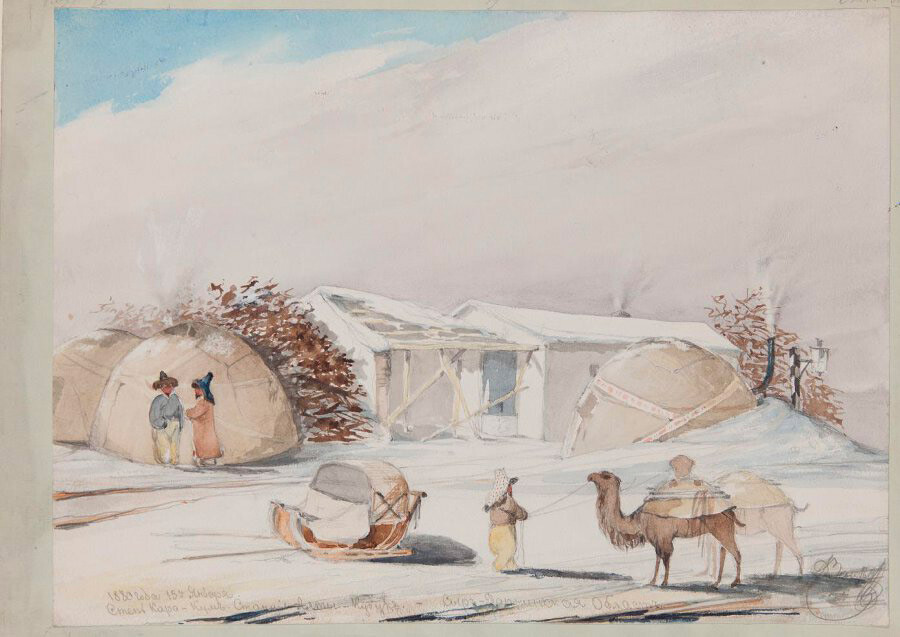

This engraver with German origins participated in several expeditions to southern Russia as an artist and left several ethnographic albums. This drawing shows a Kalmyk village with yurts, cabins, camels and carts. Geisler sketched the process of yurt construction in detail. It is believed that the Kalmyks, Buddhists living in the south of the European part of Russia, are descendants of tribes that migrated to the mouth of the Volga River from China and Mongolia.

These artworks and real artifacts from the life of nomads can be seen at the ‘Wild Field. In Perpetual Motion’ exhibition at the State Historical Museum from April 9 to September 9, 2024.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox