The Entry of Russian troops in Samarkand, June 8, 1868.

Nikolai KarazinThe British Empire always took great care to guard India, one of the main sources of its wealth and might. London reacted immediately to any encroachment on this "jewel in the crown" by any of the European powers.

Thus, the attempt by Russian Emperor Paul I, together with Napoleon, to undertake a joint campaign in India in 1801 was nipped in the bud by the British. Paul was murdered as a result of a conspiracy which Britain played no small part in organizing.

Emperor Paul I with his entourage.

Konstantin Osokin/State Historical MuseumIn the Russo-Persian conflicts of the first half of the 19th century, Britain was invariably on the side of Tehran: It provided it with financial support, sent military advisers to the Shah's army and was involved in upgrading and training the latter. Nevertheless, Russia emerged victorious from the wars of 1804-1813 and 1826-1828, which allowed it to acquire considerable territories in the Caucasus.

In the 1830s, the Russians began to actively establish themselves on the eastern shores of the Caspian Sea and attempted to advance deep into Central Asia by undertaking an unsuccessful campaign against the Khanate of Khiva in 1839-1840. All these activities didn't go unnoticed by London.

Cossacks on the march.

Konstantin Filippov"It seems pretty clear that, sooner or later, the Cossack and the Sepoy, the man from the Baltic and he from the British Islands will meet in the center of Asia," British Foreign Secretary Henry John Temple Palmerston asserted in 1840. "It should be our business to make sure that the meeting should take place as far off from our Indian possessions as may be convenient and advantageous to us."

The British, at that time, were already waging an arduous war against Afghanistan, which eventually ended in failure for them. One of the principal reasons for their invasion was Emir Dost Mohammad Khan's initiative to establish long-term cooperation with St. Petersburg.

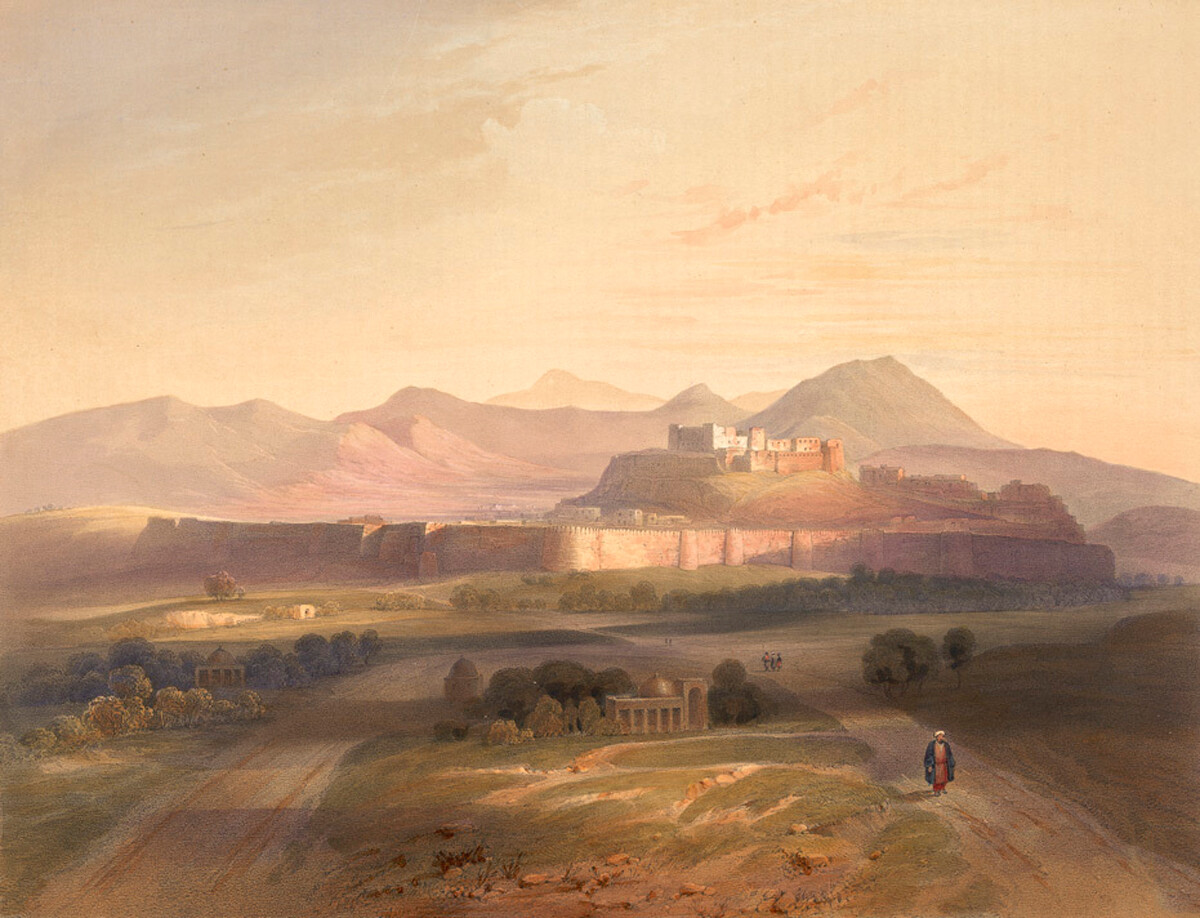

The city of Ghazni.

Lieutenant James Rattray / The British LibraryAnd so it was that the two empires were drawn into a large-scale geopolitical rivalry for Central Asia. They attempted to drive each other out of the region without, at the same time, embarking on open armed conflict. All available methods were deployed: diplomatic intrigues, espionage, bribery of local rulers, attempts to set the latter at odds with their rival and so on.

The term that came into widespread use to describe this confrontation was the ‘Great Game’ – it was coined by Arthur Conolly, captain of the 6th Bengal Light Cavalry Regiment of the East India Company. It is noteworthy that Conolly himself fell victim to the "game" – on June 17, 1842, he was accused of espionage in the Emirate of Bukhara and beheaded.

Last stand of the 44th Regiment at the Battle of Gandamak.

William Barnes WollenIn Russia, plans were drawn up to invade British India along different routes, although there was a fair amount of skepticism overall about the idea of acquiring colonies there. At the same time, St. Petersburg believed that the mere existence of such a threat would force London into a permanent state of nervousness.

"To be in peace with Britain and compel her to respect Russia's voice, while averting a break with us, it is necessary to rouse British statesmen from their pleasant delusion that their Indian possessions are secure, that Russia is incapable of resorting to offensive actions against Britain and that we lack initiative and adequate access to routes across Central Asia," Gen Nikolai Ignatyev wrote in 1863.

The Entry of Russian troops into Samarkand on June 8, 1868.

Nikolay KarazinIn 1868, the Russian Empire significantly strengthened its hold over the Central Asia region, establishing protectorates over the Khanate of Kokand and the Emirate of Bukhara. It effectively reached the border with Afghanistan, which the British had no intention of allowing the Russians to cross.

London clamped down on any attempts to establish any kind of alliance between Russia and the Emirate of Afghanistan. Thus, soon after a visit to Kabul by a diplomatic mission led by Gen Nikolai Stoletov in 1877, the Second Anglo-Afghan War broke out, resulting in the Afghans losing a number of territories and some of their sovereignty.

Gandamak, May 1879. From left to right: British officer Jenkins, British diplomat Cavagnari, Afghan Emir Yakub Khan, Afghan Commander-in-Chief Daud Shah, Afghan Prime Minister Habibullah Khan.

John Burke / The British LibraryIn 1885, the Anglo-Russian cold war almost turned into a hot one. The conflict arose over competing claims to the Panjdeh oasis (today, the town of Serhetabat in Turkmenistan) by Russia and Afghanistan, now under British protectorate.

A ferocious battle took place on the border river Kushka between Russian and Afghan troops, which ended in a crushing defeat for the latter. Calls for war began to ring out in London, but eventually the conflict was defused – Panjdeh stayed with Russia, while Tsar Alexander III provided guarantees that he would not threaten the territorial integrity of Afghanistan in future.

The Battle of Kushka.

Franz RoubaudIn the 1890s, the two empires embarked on dividing up the Pamir mountain chain. Both sides sent military contingents to the region, but, ultimately, an armed clash was avoided. Afghanistan, Russia and the Emirate of Bukhara, which Russia controlled, divided up the Pamirs among themselves.

In the early 20th century, Tibet became a new arena of great power rivalry. The confrontation led to a military incursion by British troops into the region in 1903-1904 and the signing of the Convention of Lhasa. Under one of its clauses, Tibet would henceforth be unable to permit the activities of representatives of any other power on its territory without British agreement.

The Flight of Thubten Gyatso, 13th Dalai Lama from the British invasion.

Public DomainWhile Russia and Britain were pursuing the ‘Great Game’ with one another in Asia, in Europe, the power of the German Empire was rapidly growing. Eventually, the potential danger from that quarter became obvious to both London and St. Petersburg.

In 1907, the sides signed a convention that was designed to resolve all the points of dispute in relations between the two powers. They recognized the sovereign authority of the imperial Qing Dynasty over Tibet and agreed not to interfere in its internal affairs.

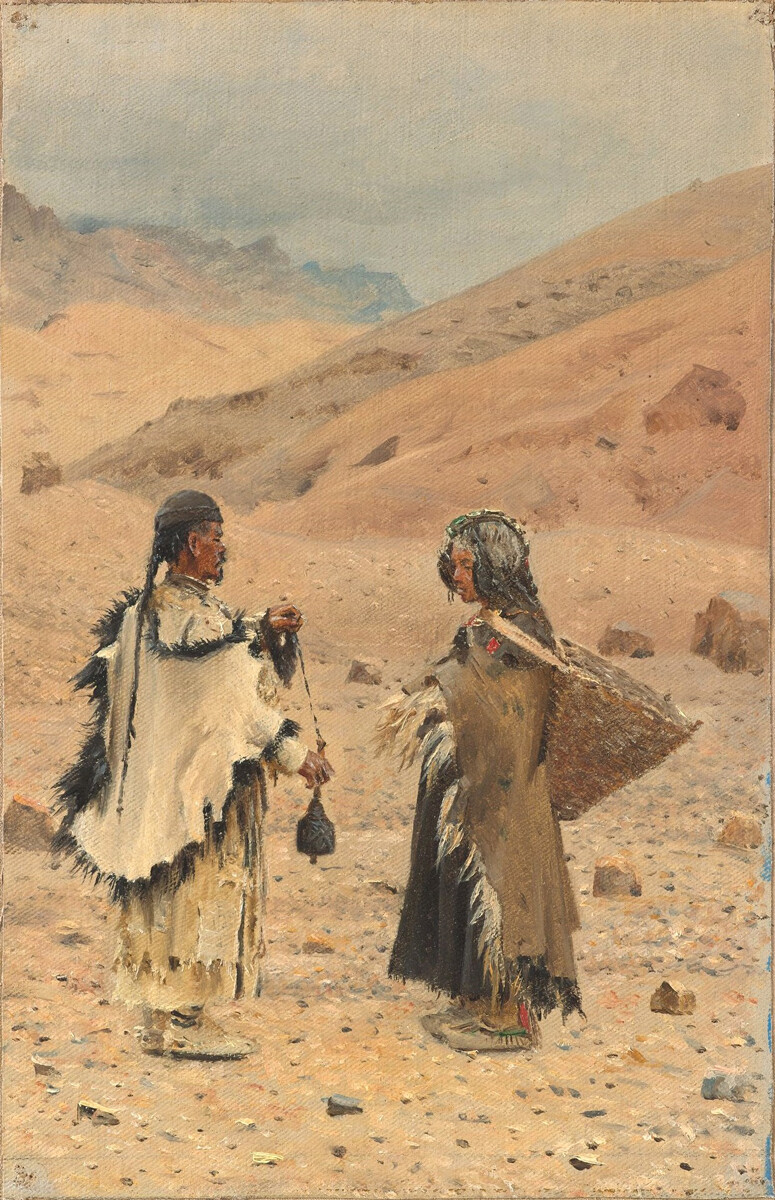

Residents Of Western Tibet.

Vasily VereshchaginPersia, meanwhile, was divided up into zones of influence. Britain pledged to respect Russian interests in the north of the country, while Russia recognized London's dominance in the southeast. A neutral zone was also set up in which both sides acquired equal trade and economic rights.

Russia recognized Afghanistan as a British protectorate and acquired the right to develop economic and cultural (but not political) ties with the Emirate. Overall, the sides tacitly agreed to regard the Asian country as a buffer between British India and Russia's Central Asian possessions.

And with that, the ‘Great Game’ was over. The former adversaries became allies and concentrated on strengthening the military-political bloc that was to become widely known as the ‘Entente’.

Triple Entente.

Public DomainIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox