Little-known quirks of some great Russian authors

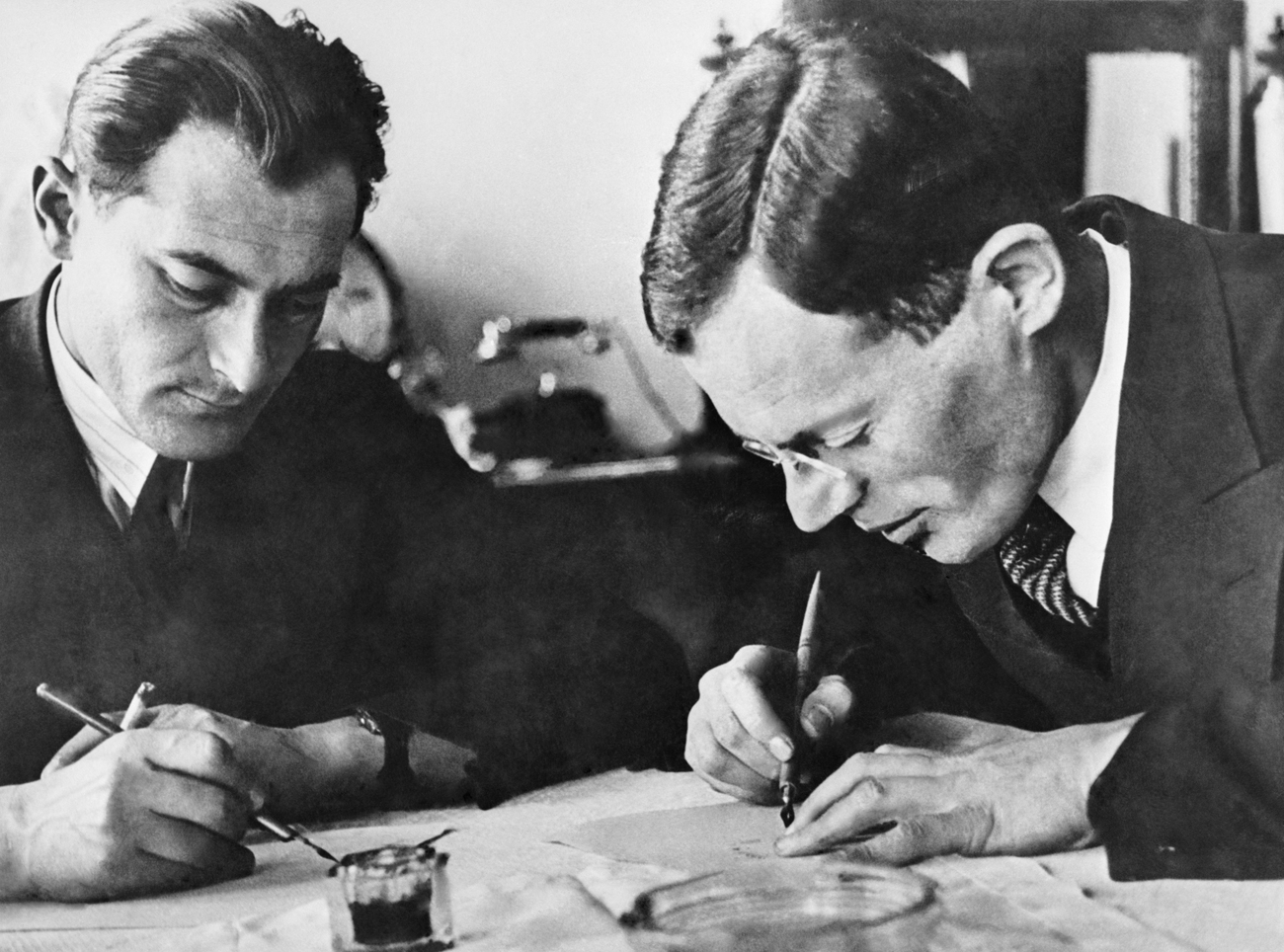

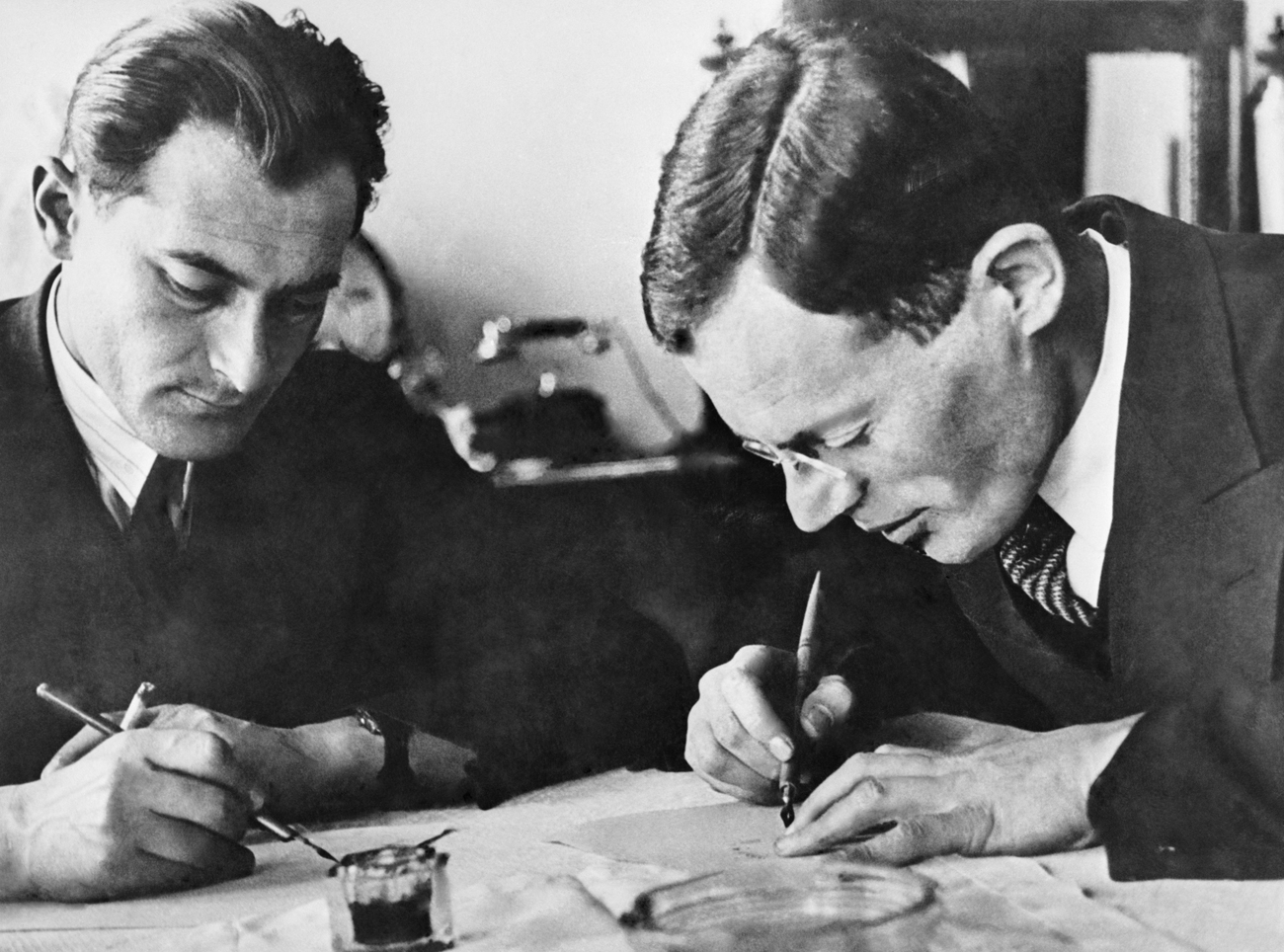

Ilya Ilf (R) and Yevgeny Petrov at work.

TASSAlexander Pushkin

Alexander Pushkin was well-known for being extremely superstitious, sometimes verging on paranoia. On several famous occasions, however, his apparently random premonitions did come true. Pushkin decided in December 1825 to make an escape from his mother's rural estate of Mikhailovskoe (Pskov Region, 350 miles north-west of Moscow), where he was in exile.

As he was making his way to St. Petersburg, a hare crossed in front of his carriage. Pushkin considered this to be a bad omen so he immediately returned to the estate. The twist in the tale was that this took place on the eve of the December Uprising, when a group of noblemen demanded restrictions on the Tsar's powers and a Constitution.

The fact that Pushkin did not continue to St. Petersburg meant he did not join the revolutionaries on Senate Square – an act for which most of them were handed lifelong imprisonment in Siberia. This was among Pushkin's favourite stories, which he would often retell.

Twenty years before his tragic death in a duel, Pushkin was told a prophecy that he would be killed by a "white man" with a "white head". Pushkin was mortally wounded in a duel in 1837 by Georges d’Anthes, who was wearing white coat and had blond hair.

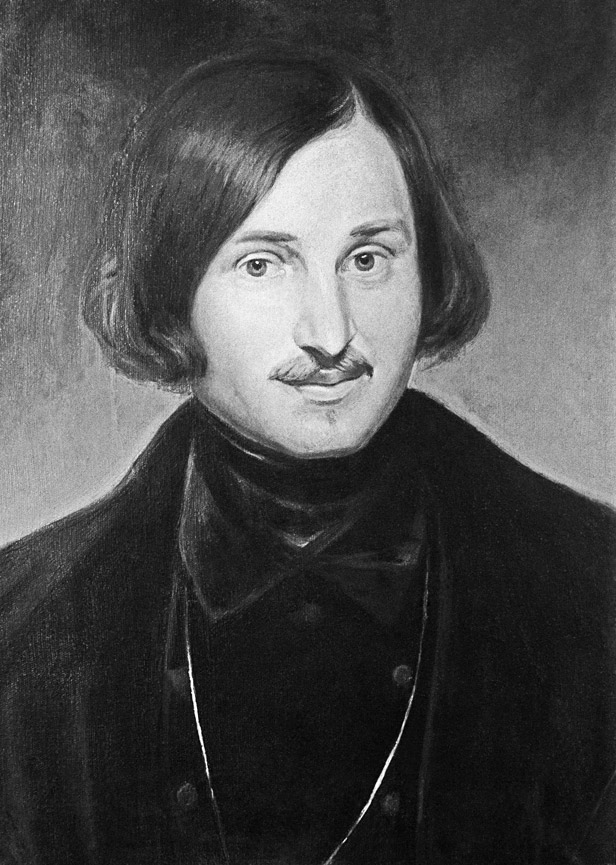

Nikolai Gogol

F.A.Moller. Portrait of Nikolai Gogol. Source: Press photo

F.A.Moller. Portrait of Nikolai Gogol. Source: Press photo

Nikolai Gogol had numerous eccentricities and worries, but the one that haunted him the most was taphophobia: a fear of being buried alive. To prevent this awful fate, he would sleep sitting upright and included a special clause in his will requesting that he be buried only when his body was clearly decomposing.

Gogol died in 1852 and was reburied in 1931. Some witnesses to the exhumation reported that the writer's body was in an unnatural pose. Was that pure coincidence, or the last movements of a man whose worst fear had come true?

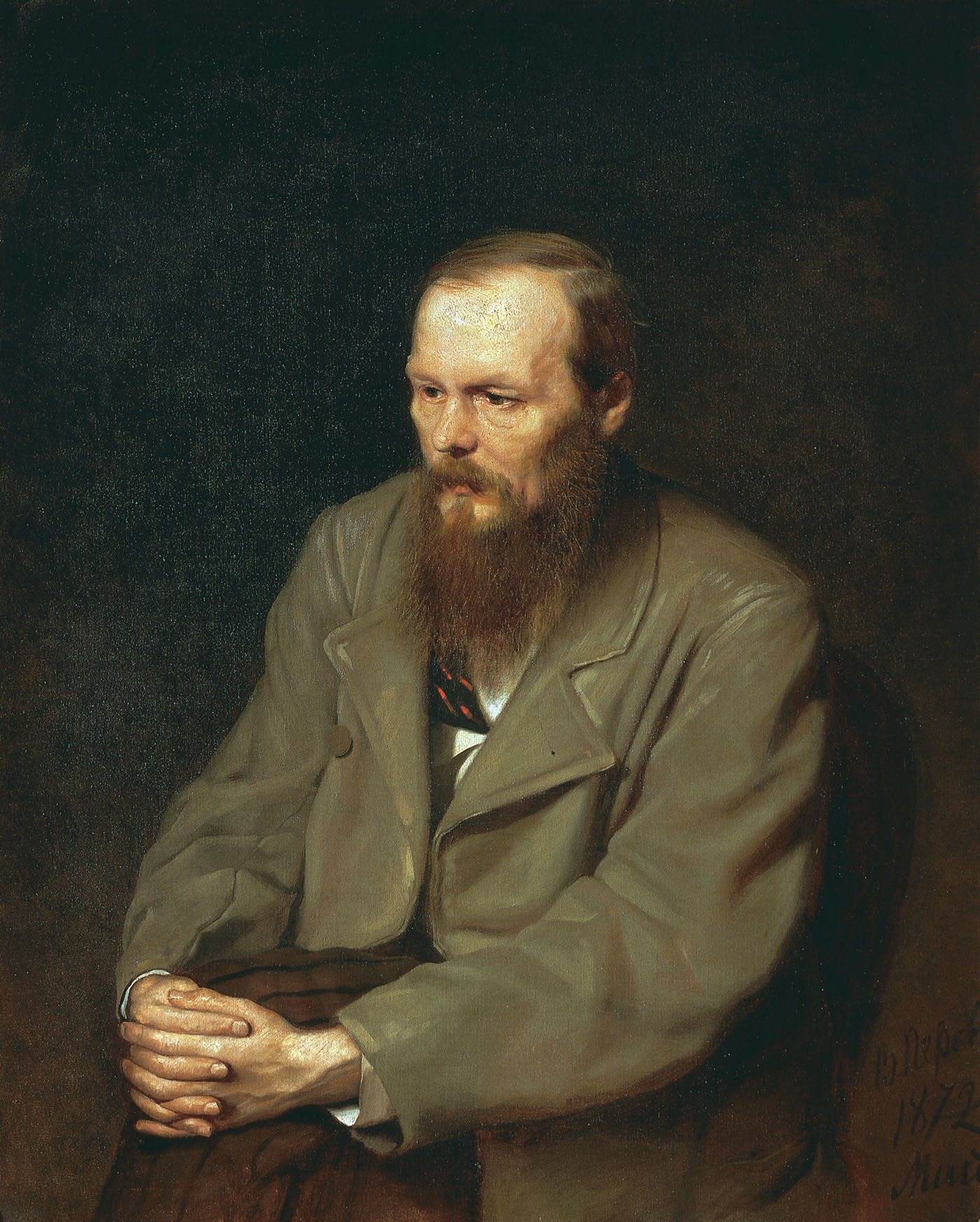

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Vasily Perov. Portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky. 1872. Source: State Tretyakov Gallery

Vasily Perov. Portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky. 1872. Source: State Tretyakov Gallery

The rock of Russian literature, as Fyodor Dostoyevsky is known, is renowned for his vibrant, energetic prose. He, however, also had a strong propensity to fall into a deep, catatonic sleep – a side effect of his epilepsy.

"Every time he went to bed, he would ask me not to bury him for at least three days if he succumbed to catatonia," recalls Konstantin Trutovsky in ‘Memoirs About Dostoevsky’, the first book about the writer. "He had a perpetual fear of it."

Dostoevsky was widely known for his unstable physical and mental health, even raising the interest of Sigmund Freud, who wrote several articles about the writer.

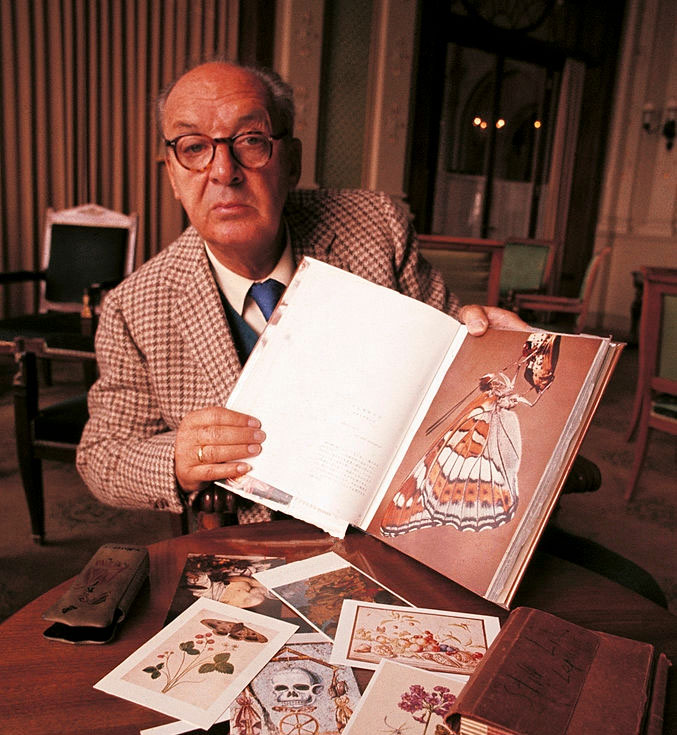

Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Nabokov. Source: wikipedia.org

Vladimir Nabokov. Source: wikipedia.org

Many writers have a special ritual that helps their creative juices flow. Vladimir Nabokov, however, took it to entirely another level. He wrote his novels on small rectangular index cards that held around 150 words each. He would work in a non-linear way, writing down random ideas as they came to him, only numbering and combining the cards into a single text right at the end of the process.

This atypical way of working gave his publishers a real headache when it came to his final, unfinished novel, The Original of Laura. He had not numbered the 138 cards before he died and it took almost 30 years of debate for a version to be released. Whether it is the version Nabokov planned is a matter for another few decades of discussion.

5. Yevgeny Petrov

Yevgeny Petrov (L) and Ilya Ilf at work. Source: TASS

Yevgeny Petrov (L) and Ilya Ilf at work. Source: TASS

One of the co-authors of Little Golden America and The Twelve Chairs was nothing if not a wistful character. One of Yevgeny Petrov’s favourite pastimes was writing letters to people who did not exist. He would come up with fictional names and addresses and send the letters to different parts of the globe. When these letters were inevitably returned to sender, Petrov would take delight in receiving the envelopes covered in numerous foreign stamps and postmarks.

It was a foolproof system – seemingly. Legend has it that Petrov sent a letter to New Zealand in April 1939, using his tried-and-tested method of inventing a destination and recipient, in this case a Merill Eugene Wellesley. When the undelivered letter did not return to him in a few months, he decided that it had simply got lost in the system. However, in August that year, he received a letter from New Zealand in the mail. It was a clear and direct reply to Petrov's own message to Wellesley. It even included a picture of the writer hugging a man he had never seen. In an attempt to work out just exactly what was going on, Petrov wrote a second letter to the mysterious Wellesley, but he died before he could receive the reply.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox