From Leh to St. Petersburg: How Pashmina shawls reached 19th century Russia

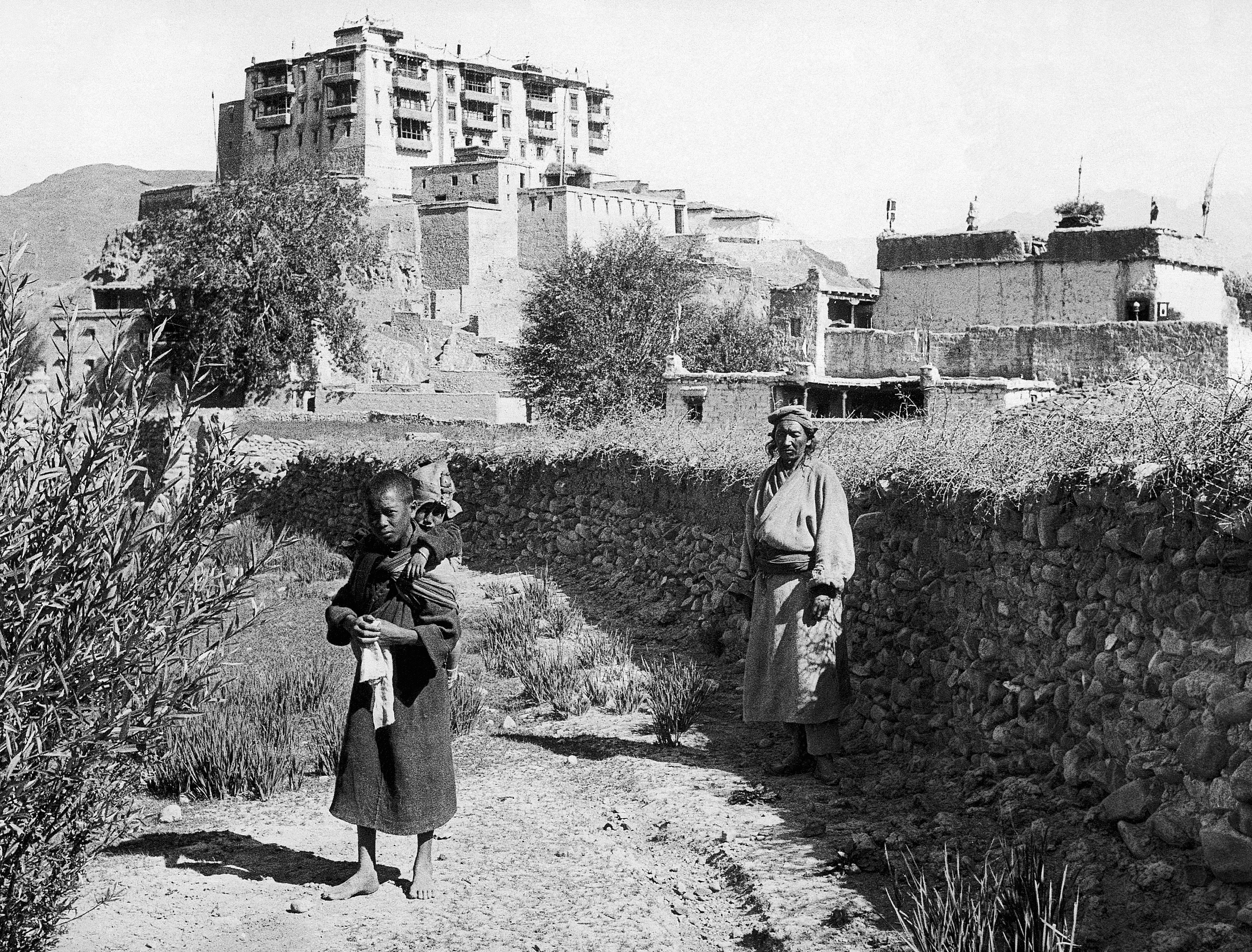

Russia's trade links to Ladakh go back to the early 19th century. Source: AP

Ever since Afanasy Nikitin documented his 15th century voyage to India, Russian Tsars wanted to establish direct trade links with India. Products from India managed to reach Russia via Astrakhan, where an Indian community sprang up, and through the old Silk Route. One exotic accessory from India took early 19th century St. Petersburg by storm - the Pashmina shawl.

Pashmina, which means soft gold in Kashmiri, became a craze in Russia’s imperial capital, after the shawls made their way to the city through Central Asian caravan traders, who bought them from traders in Leh.

“The best known among pioneer Russian and Russia-connected caravan traders was Mehti Rafailov,” historian Alexander Andreyev wrote in a research paper titled ‘Russian Travellers in Tibet.’ “A Jew from Kabul, he first worked as a prikazchik (merchant's clerk) of a thriving merchant Semion Madatov, and it was Rafailov who, as early as 1807, delivered directly to St Petersburg several bales of Kashmir shawls, a commodity then at the height of fashion with the Russian ladies’ beau monde.”

According to Andreyev, the Tsarist authorities took notice of this and Foreign Minister Count Nicholai Rumiantsev summoned Rafailov and encouraged him to develop a two-way trade link between Russia and northern India.

Between 1808 and 1820, Rafailov made several trips to Ladakh and Kashmir. “The route generally favoured by Rafailov and other merchants heading for Ladakh and on to Kashmir from Russian territory, started at the Semipalatinsk Fortress on the Irtysh River (in southwest Siberia, the main military outpost in the Siberian frontier line) and led across the Kirghiz steppes to Kulja, a little town in Chinese Turkestan and the closest one to the Russian border,” Andreyev wrote in his book titled ‘Soviet Russia and Tibet. The debacle of Secret Diplomacy. 1918-1930s.’ “From there caravans travelled south to Yarkand, via Aksu and Kashgar, and from Yarkand into Ladakh after crossing several high mountain ranges.”

Rafailov was welcomed by the ruler of Ladakh in Leh, and allowed to conduct his trade to and from Russia. Such was the popularity of Pashmina shawls in Russia that the Russian authorities even wanted the Afghan trader to bring back goats from Kashmir so that the shawls could be made in Russia. According to Andreyev, the rulers of Ladakh prohibited the export of the sheep and this in addition to the fact that the animals may not have survived the long journey to Russia led the Afghan trader to come up with another idea. Rafailov thought of buying the softest fleece and bringing to St. Petersburg so that the shawls could be made in Russia.

Russian outreach to Indian Kings

Tsar Alexander I took a particular interest in Rafailov’s travels and was keen to build up trade ties with Indian princely states. Just around the time the East India Company was making inroads into India, Russia looked to build trade with Indian kingdoms.

Rafailov met the rulers of Ladakh, Kashmir and Punjab. In 1819, Russia’s new Foreign Minister Konstantin Nesselrode reached out to these rulers via letters that were sent with the Afghan trader.

“In these missives, all written on the same pattern, Nesselrode wrote that the Russian emperor, Alexander I, having learnt through Rafailov of the ‘glory, splendour and power’ of these Indian rulers, as well as the hospitality they showed to visiting Russian merchants, enjoined him (Nesselrode) to ‘enter into friendly intercourse’ with these three sovereigns via his ‘loyal and diligent officials’ so that both Russian and Indian merchants ‘could travel freely to their reciprocal regions,’” Andreyev wrote.

The great Sikh ruler Maharaja Ranjit Singh even sought the aid of the Russian Empire to ward off the British who attempted to make him their vassal.

It is clear from the letters that were written by Nesselrode that Russia wanted friendly ties with Indian rulers unlike the British who aimed to subjugate and colonise India.

During an expedition to India in 1820, Rafailov fell sick and died. Some accounts claim he was murdered. During the 12 years that he operated as a trader and political emissary between Russia and India, Rafailov provided Russia with some of its earliest accounts of Ladakh, Kashmir and other parts of northern India.

“Rafailov’s service to the Russians, which conveniently combined trade and diplomacy, proved fairly successful,” Andreyev wrote. “He showed himself quite a skilful Great Gamer, having succeeded in forging a rather promising Russia-northern India link.”

Four decades after Rafailov’s death, India came under total British rule. India would remain a part of the British Empire until 1947, when the Brits fearing a pro-Russian regime in India divided the country on religious grounds. A few years after the partition of India, Tibet and East Turkestan came under Chinese rule, almost permanently blocking an easy land route between Russia and India via Central Asia.

Ajay Kamalakaran is RBTH’s Consulting Editor for Asia. Read more of his articles here. Follow Ajay on Twitter and Quora.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox