Did Russia’s last Tsar fall prey to a conspiracy hatched by the Masons?

Alexander Feodorovich Kerensky (1881-1970) Russian revolutionary leader. Minister for war in 1917.

Mary Evans/Global Look PressAlexander Kerensky was best known in Russia as a deputy of the State Duma, the lower house of Parliament. He made his most famous statement just days before the February Revolution in 1917:

“The historical task of the Russian people now is the immediate destruction of the medieval regime…There is only one way of fighting those who break the law, and that’s their physical destruction.”

He uttered these words less than two weeks before the uprising. Empress Alexandra Feodorovna was appalled by what he said and wanted him hung. However - in a twist of fate - her life and and lives of her closest relatives would soon depend on Kerensky.

He entered the Duma in 1912 as a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. After becoming a deputy Kerensky joined a Masonry society - as was the fashion of many parliamentarians. He became the general secretary of the Supreme Council of Grand Orient of Russia's People, an influential Masonic lodge uniting many famous political figures, most of whom worked in the Duma. On account of this - and his ill words aimed at the Tsar and the Imperial establishment - Kerensky was suspected of being involved in a Masonic conspiracy to topple and kill Russia’s monarchy.

Kerensky and the uprising against the Tsar

A possible conspiracy hatched by the Masons, as a main driving force behind the events in February 1917, has been a popular theory used to explain the blistering collapse of the Imperial order. There is a long tradition of scholarly research discussing the possible impact the Masons had on the Revolution. According to historian Piotr Multatuli, Kerensky played a prominent role in the events of 1917 due to his Masonic ties in Russia and abroad.

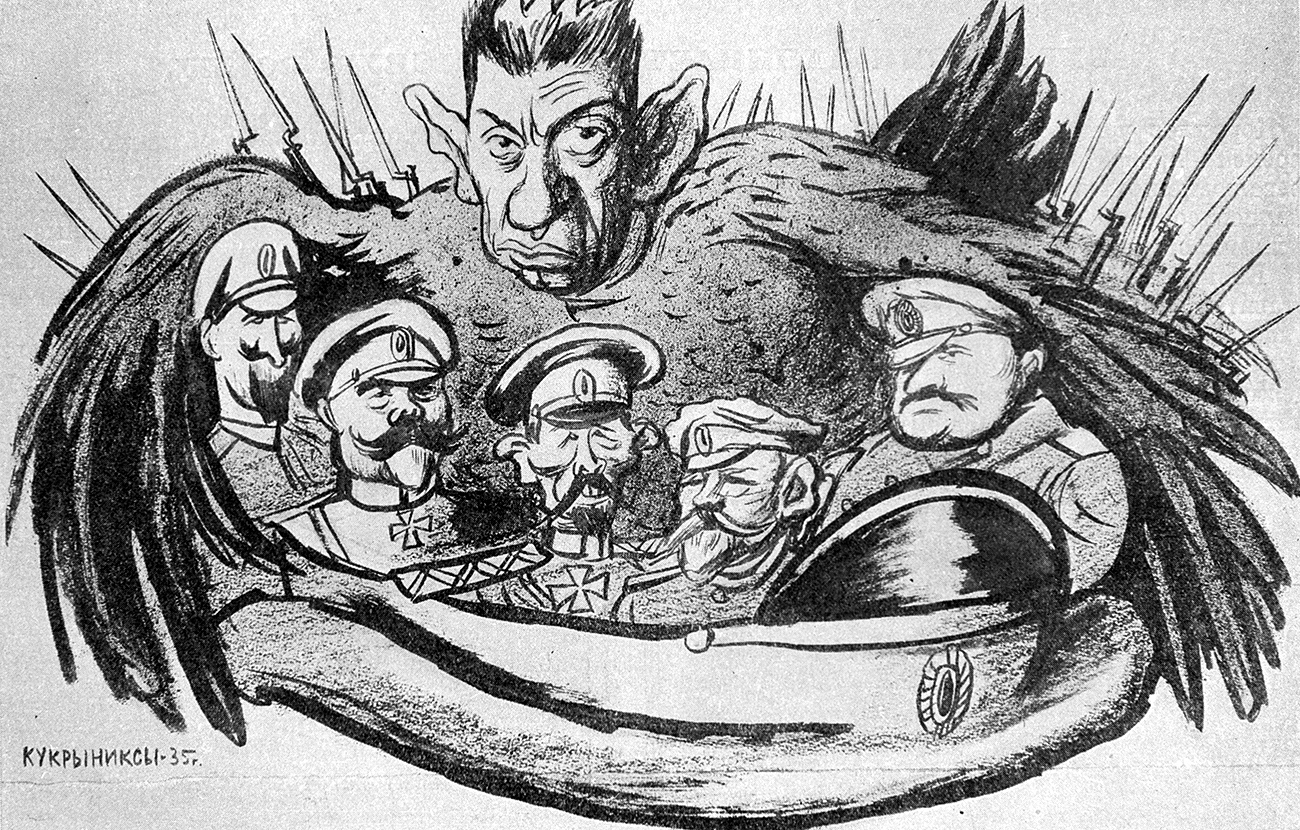

Freemason Kerensky is alleged to have been involved in yet another conspiracy – the revolt of General Kornilov. / RIA Novosti

Freemason Kerensky is alleged to have been involved in yet another conspiracy – the revolt of General Kornilov. / RIA Novosti

During that famous February, Kerensky played a big hand in snatching power from royal hands and passing it to the Duma. He also welcomed troops that swore their allegiance to the government. He was against the idea of giving the Russian throne to Nicholas’ brother, Mikhail.

Kerensky was also the only person who had one foot in each of the camps that shared power in post-tsarist Russia: The Provisional Committee of the State Duma (that would turn itself into a government) and the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. Multatuli argues that Kerensky’s activities at the time were heavily influenced by the Masons, and believes that when he became minister of justice in the provisional government (and prime minister in July), the fraternal group maintained its standing.

Kerensky and the arrest of Nicholas II

As Multatuli asserts, Kerensky was one of the key political leaders behind the decision to arrest the Tsar and his wife after the success of the uprising in Petrograd, before preventing them from leaving Russia. However, the move was made under the influence of both the French and British ambassadors.

“The decision to arrest the royal family was taken under pressure or by a direct order from abroad,” the historian wrote, quoting another prominent politician - Pavel Milyukov - who argued that back then, British ambassador George Buchanan had tremendous influence over Kerensky.

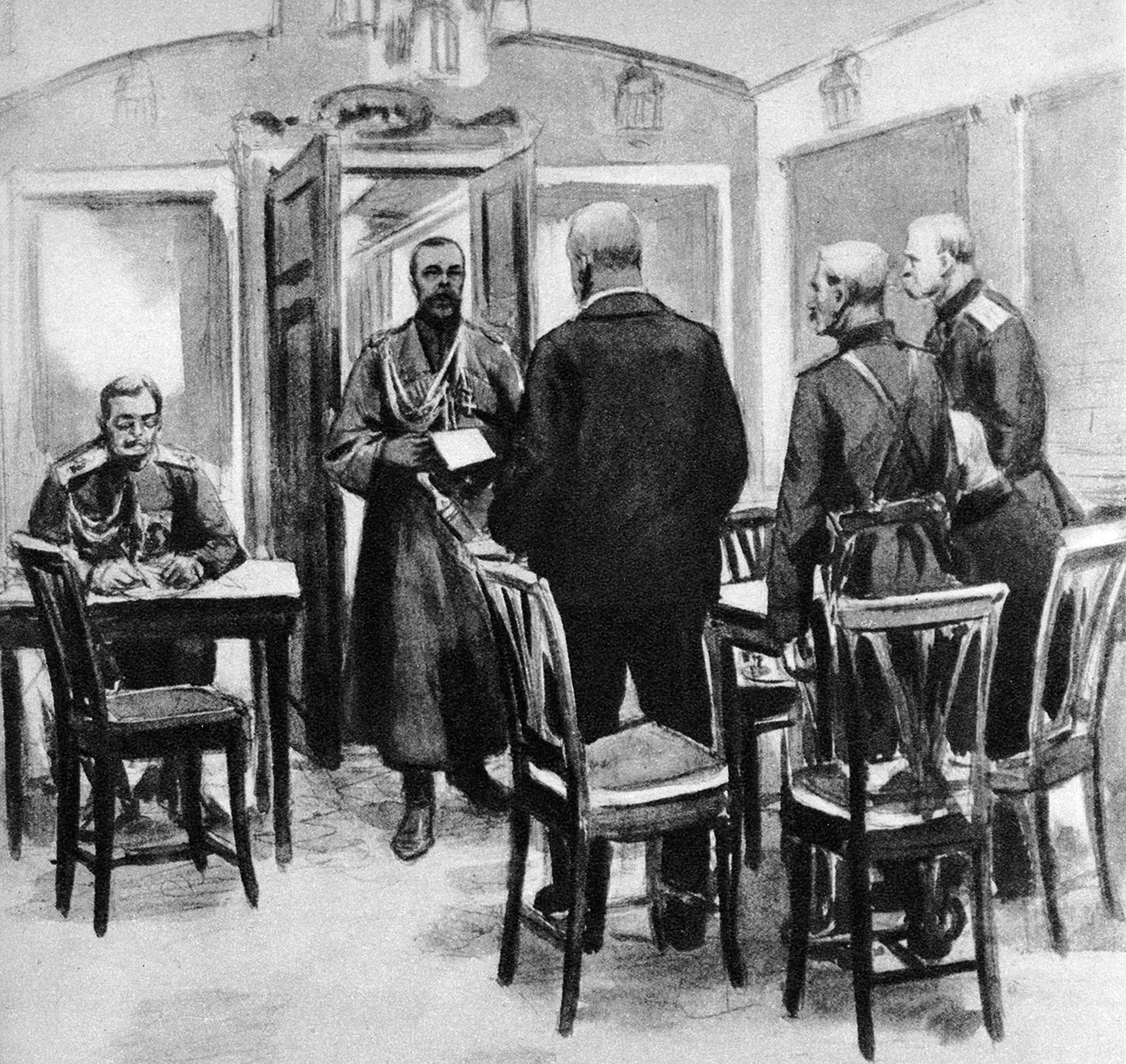

Russian Revolution, Tsar Nicholas II, the last emperor of Russia, reads the act of abdication to the messengers of Kerensky the Duma in its direct private wagon at Tsarskoye Selo. Illustration of the scene which occurred March 15, 1917. / Getty Images

Russian Revolution, Tsar Nicholas II, the last emperor of Russia, reads the act of abdication to the messengers of Kerensky the Duma in its direct private wagon at Tsarskoye Selo. Illustration of the scene which occurred March 15, 1917. / Getty Images

There is a view that Britain did not want to accept the Tsar due to his alleged sympathies toward the Germans amidst WWI. That is why the diplomat allegedly pressed hard on the new Russian authorities to deal with the Tsar. Kerensky himself said that Nicholas II was kept in the country because Britain did not want to take him. Minister of Justice Kerensky supervised the royal family’s situation in Tsarskoe Selo from March to July.

Moving the Tsar to Siberia

If Kerensky’s role in overthrowing the monarchy is not clear, the same cannot be said for the fate that awaited the Tsar and his family. In July, when Kerensky was appointed prime minister, the royal family was turfed out of Tsarskoe Selo and sent to the Siberian town of Tobolsk. He said it was no longer safe for them to stay so close to Moscow.

Tsar Nicholas II just before he was shot, Ekaterinburg, July 1918. / Global Look Press

Tsar Nicholas II just before he was shot, Ekaterinburg, July 1918. / Global Look Press

In early July Petrograd was rocked by sailors and soldiers revolting under the Bolshevik banner. The government managed to suppress the movement, but Kerensky was apparently sure that had the Tsar not been in Siberia, he would have been killed in 1917 - instead of the following year.

Kerensky asserts in his memoirs that although the decision to transfer the royals was taken by the cabinet, Tobolsk was chosen by him. Its remoteness “did not allow to think about any spontaneous incidents.” In early August, the royal family was moved to Tobolsk and put up in the ex-governor’s house. There they stayed until 1918 when they were transferred to Yekaterinburg, where the Romanovs were ruthlessly murdered in a basement on July 17.

Read more: 10 important facts about the murder of Russia’s royal family

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox