Crossing Siberia by horseback: The story of an intrepid 19th-century couple

Nick Fielding in Kazakhstan. Source: Personal archive

Nick Fielding in Kazakhstan. Source: Personal archive

Thomas Atkinson was an architect and accomplished artist who traveled to Russia in the late 1840s during a lull in his professional career. He fell in love with a young English woman called Lucy who was working as a governess in the influential family of General Mikhail Muravyev. This connection allowed Atkinson the opportunity to show his paintings to Tsar Nicholas I, who gave him permission to travel to Siberia to draw the landscape. In their ensuing seven-year journey, Lucy and Thomas traveled around 40,000 miles across rugged terrain on boats, horseback and in carriages.

RBTH met Fielding at the Krasnoyarsk Book Fair to talk about this epic journey and his mission to repeat it.

RBTH: Why did Atkinson travel to Siberia?

Nick Fielding: At first he wanted to paint it, but as the journey progressed and time passed – we’re talking about seven years in Siberia and more than a decade in Russia – it grew to be about more than this. He became fascinated with Siberian culture and the people of Central Asia in particular.

The only modern image of Thomas Atkinson. Source: courtesy of Paul Dahlquist

He was very interested in the Decembrists - aristocratic revolutionaries who led a failed uprising in 1825 - and the milieu of the time, which definitely marked him out to the Tsarist police. I’m sure there’s a huge archive of reports on Lucy and Thomas’s movements somewhere in Russia, but I haven’t located it yet.

In her book Lucy says that it wouldn’t have been a punishment for her to be arrested and sent to Siberia: they were not afraid of the climate, the harshness and the isolation. They had a very positive view of Siberia’s people and its culture.

Irkutsk and Barnaul were two intellectual cities that were quite radical at the time because of their high number of exiled anti-tsarist political figures. Barnaul was noted for its beautiful museums and very free conversations in salon meetings. This was in stark contrast to St. Petersburg, for example, where the tsar’s spy network was very active and people were continually looking over their shoulder.

RBTH: Did Lucy describe this in her book?

N.F.: They both discuss it, but Lucy in particular. Thomas was setting out his travels, but Lucy was more open to talking about what happened when they traveled. I should point out that a lot of Lucy’s book was based on Thomas’s diaries, which I’ve also read. I can tell you that he was thinking about these issues too, but he didn’t write about them.

RBTH: What were your reasons for traveling to Siberia?

N.F.: I first came to Central Asia more than 20 years ago, and since then I’ve been back many times to Siberia, Tyva, Kamchatka, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Mongolia. I’ve always enjoyed traveling in the region and have hiked thousands of miles there. I was also interested Central Asian textiles, and I was curious where the designs came from: they were being made by Muslims but without Islamic designs. The answer was that they came from Siberia.

"It wouldn’t have been a punishment for her to be arrested and sent to Siberia." Source: Nick Fielding

I discovered that Siberia itself is a wonderful place, and I began researching who else had been here and what they’d written about it. I read everything I could – I’ve got an enormous collection of books about Siberia going back hundreds of years to the earliest travelers. I came across the Atkinsons and wondered why they have been largely forgotten by history. They’re an extraordinary couple – two of the greatest travelers of all time.

RBTH:How important was Lucy’s presence to the success of the trip?

N.F.: Very important. I think Thomas wanted to travel with Lucy partly because she spoke Russian and he didn’t. She had already been living in St. Petersburg for eight years and was a governess in a Russian family, so she also knew how Russian society worked. 19th-century Russia was very stratified: everybody had their place, and you had to know who you could speak to and how you could speak to them. Lucy knew that very well.

She was a woman of action who wasn’t frightened – or perhaps she was frightened but was still brave – and she actually saved his life on one occasion. She would carry guns, and when two men grabbed him from behind she pulled a weapon, pointed it at them and demanded they let him go. He picked a very good traveling companion, in my view. Particularly when you consider the general difficulties of the trip.

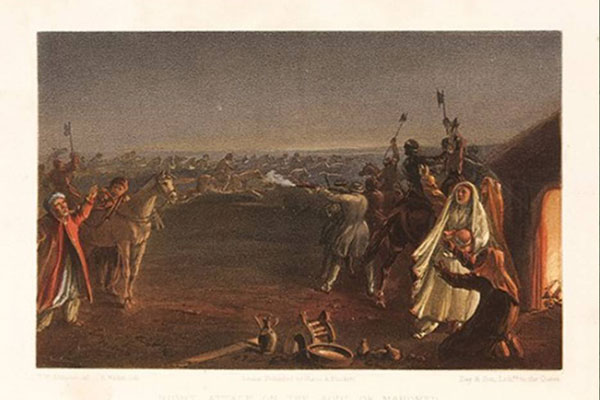

Presumably on this painting Thomas is shooting in local gunmen. Source: courtesy of Nick Fielding

RBTH: What were some of these difficulties? For you as well as them.

N.F.: Their trip was made incredibly complicated by the fact that she became pregnant almost immediately. She was crossing really fast-flowing rivers on horseback up to her knees. When the baby was delivered two months prematurely in Qapal [Alma-Ata Region, modern-day Kazakhstan], the Cossack doctor, who was only 23, told her that this had been caused by riding horses.

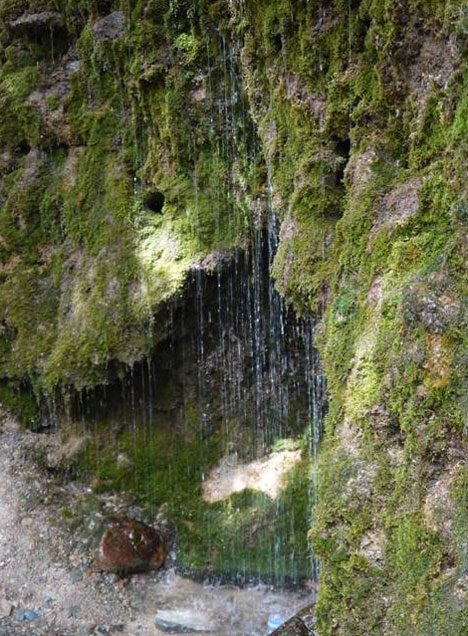

Fortunately, the baby survived, and the couple named him Alatau Tamchibulak Atkinson in honor of the Alatau mountains and the beautiful "diamond" spring in what is now Kazakhstan.

Tamchibulak, the 'diamond' spring. Source: Nick Fielding

Lucy could well have demanded to turn around and go home right out in the middle of the steppe, but she didn’t, and that is to her great credit.

As for me, when you are hundreds of miles from anywhere, the smallest thing can be dangerous. But still I got enormous pleasure and excitement from those trips. I met people in Tyva that had never met Europeans before. So I’ll continue traveling in Siberia – I want to go to Altai, the northern Sayans, near Irkutsk, and to Lake Baikal.

On a practical level, one of my biggest problems was looking for documents in the Russian archives. I don’t speak Russian, so I can only talk to Russians via Google Translate. I also paid people to look through documents and send me anything interesting they found.

RBTH: Did you contact any of Atkinsons’ descendants?

N.F.: I am in touch with them. Some of the family lives in England, and there are others in Hawaii, where their son emigrated – I’ve visited them over there.

The family has preserved some wonderful items: they still have the samovar that Thomas and Lucy took with them all around Siberia, and Lucy’s little penknife. When Belinda Brown, a direct descendant, handed me the knife, I was trembling, because it contained so much travel. I am emotional even now, talking about it.

They also have a couple of earrings that Lucy got in Altai and a gold nugget that a man from Krasnoyarsk called Vasilevsky gave them. In exchange Thomas gave him a painting, which is now in the museum here in Krasnoyarsk.

Nick Fielding’s book South to the Great Steppe is published later this month. It chronicles the Atkinsons’ first journey south to Semirechye [Zhetysu Territory in Central Asia, modern-day Kazakhstan], the region near Lake Balkash and Lake Ala-Kul.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox