Retracing the India of the “Soviet Jules Verne”

Alexander Belyaev / RIA Novosti

Alexander Belyaev / RIA Novosti

The much-acclaimed popular science fiction writer Alexander Belyayev died almost 75 years ago (in January 1942), in a suburb of Leningrad besieged by the Nazis. Bedridden with spinal tuberculosis, he had no chance of surviving starvation and bitter cold. His death passed unnoticed at the time. He was to be mourned later, as Russia’s first and extremely popular science fiction writer.

It is difficult to imagine the sheer appeal Belyayev’s books held for an entire generation of Soviet readers. His novels and short stories were devoured by avid readers, young and old, in the USSR. Armed with a formidable knowledge in various branches of science, Belyayev prefigured in his books in the 1920s–30s such latter-day achievements as organ transplantation (“The Head of Professor Dowell”, “The Amphibian Man”), hormone therapy (“The Man Who Found His Face”), space missions and space stations (“The KEZ Star”), underwater TV and ultra-sonography (“Mysterious Eye”).

His books also kindled a genuine interest in science and technology among his readers. Some of Belyayev’s novels were praised by sci-fi stars like Herbert George Wells. The “Soviet Jules Verne”, as Belyayev was popularly addressed, firmly believed, like his revered French predecessor, in science and technology as a benign force promoting human progress. Belyayev was, however, wary of profit-spinning as he believed science must be used for serving people, not making money. In one of his novels, “The Air Seller”, a profit-greedy capitalist ventures to sell off the Earth’s atmosphere to the Martians!

What makes Belyayev especially interesting for Indians is that his last novel, “Ariel” (1941), published shortly before his death, was on India. The writer could not even dream of visiting India. His disease restricted his travel in the USSR and the policies of the British colonial masters who spared no efforts to block any contact between India and the Soviet Russia, made such a trip impossible. Nevertheless he placed his story in India, following the footsteps of Jules Verne who had also never visited India and still wrote on it in some of his novels.

“Ariel” is the story of an English boy, the orphaned son of a rich landlord. After his father’s death, two lawyers yearning to grab the child’s inheritance, bring him to Madras (now Chennai, the capital of Tamil Nadu) and place him in Dandarat, a secret boarding school run by the Theosophical Society. This school is famous for all sorts of “godmen”, “mystics”, and “neo-gurus” to support religion as a foundation of social order and to keep India under colonial dominance. He was subjected to education in religious traditions with no reference to real life, his curriculum comprising brain-washing, hypnoses, spiritism and mystical trances. This mumbo-jumbo was a ploy by avaricious lawyers to make Ariel lose his sanity so that they could claim all his money.

At the beginning of the novel, Ariel, now a youth and school graduate, is selected for an experiment by a scientist with a Stevensonian name, Mr Hyde. After an operation and infusion of some substance into his blood, Ariel is turned into a “flying man” who can fly without any wings or machine. This promised a sensational project of a “living god”. However, the school’s draconian measures failed to ruin Ariel’s mental and physical health. Along with a little Indian boy Sharad, a novice in the school whom Ariel loves like a brother and is determined to save, he flies away towards new adventures: finding shelter with a poor “untouchable” Nizmat, whose grand-daughter, a teenage widow Lolita, Ariel falls in love with; imprisonment in a local Raja’s palace, chases, escapes... The story unfolds against the background of colonial India with all its grandeur and contrasts -- temples and palaces, opulence of the elite and poverty of the masses, prudence of the “white Sahibs”.

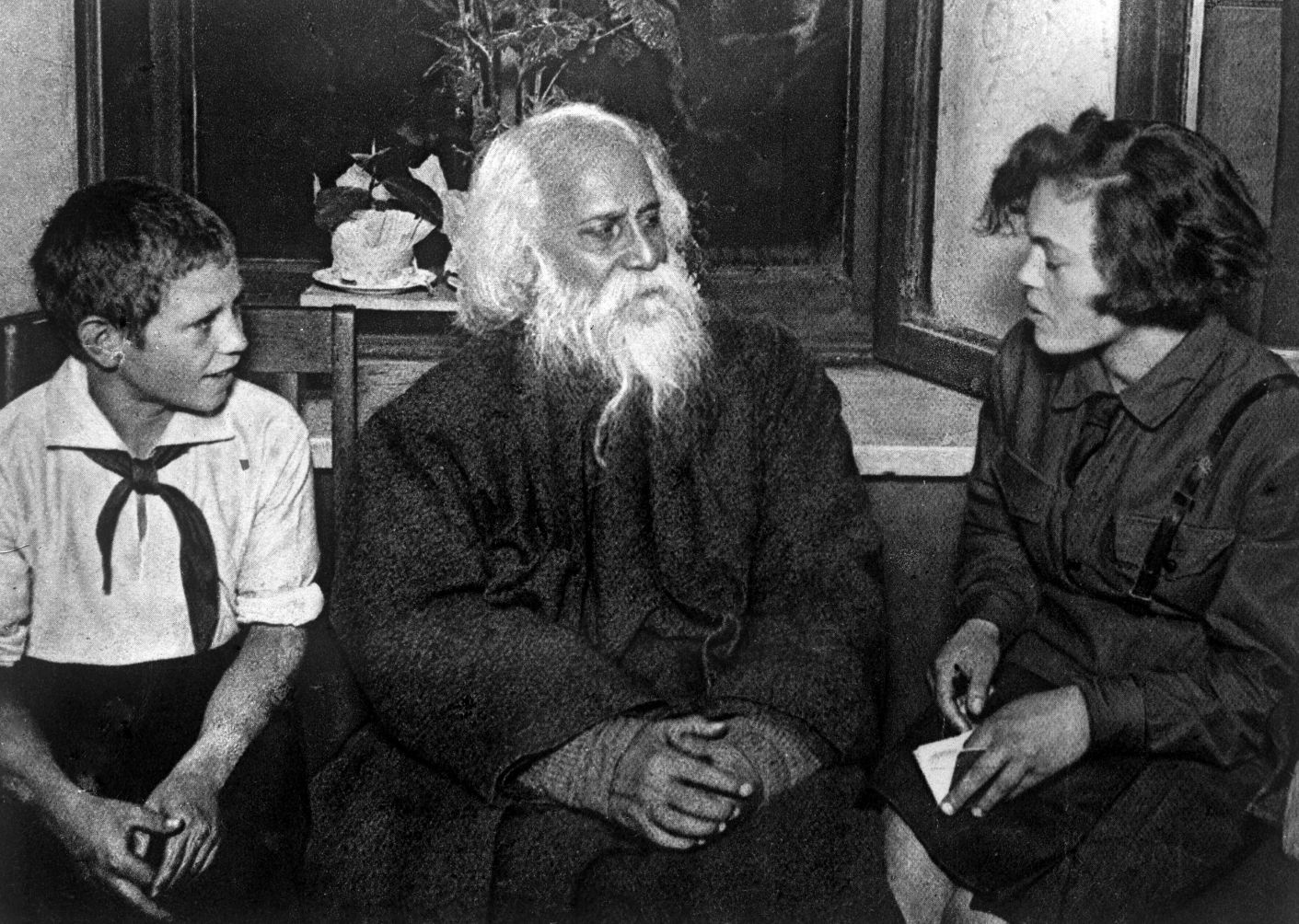

Incredibly, Belyayev’s evocation of India of that time was very true to life with only minor lapses like “Rajina” instead of “Rani”. The bed-ridden writer was fond of reading just about anything he could get on India. One of his sources was undoubtedly the Poet-Laureate Rabindranath Tagore whose lyrics, dramas and stories had been published copiously by then in Russian translations. The heroine’s name, Lolita, was definitely prompted by Tagore, as well as Kabuliwala, an Afghan dry fruit vendor, who offered some grapes to the starving Ariel and Sharad.

At first glance, “Ariel” is a common story of a “white man in India”, the clichéd subject of many a novel written by the British and other foreign authors with all their biases. But Belyayev’s approach was different from that of his predecessors and contemporaries.

For him India was neither an exotic wonderland nor an abode of cruelty and cunning and sinister “natives”. Nor was it a “sleeping beauty,” unchanged or degraded since remote antiquity, as it was for Orientalists. Belyayev’s India was a vibrant society, a battleground between the good and the evil like any other place in the world. It was different, but by no means hostile. Belyayev mentioned not only old traditions like widow self-immolation (sati), asceticism, child marriages, fanaticism and prejudices, but individuals and groups opposed to them, like the Brahmo Samaj.

In a telling episode, Ariel’s sister Jane, before travelling to India in search of her brother, leafs through books and encyclopaedia for information on India. What she finds is an “enormous chaotically swarming anthill” of races, colours, castes, tribes, languages, religions, with the whole array of Orientalist writings on India’s “mysteries” and “horrors”. This is followed by the author’s observation: “On the new India, its new men and new women, Jane’s books were silent”. Indeed, India’s “new men and women”, who struggled for freedom, social uplift and justice, had been well known and admired in the then USSR long before others woke up to them.

As early as the 18th and 19th century, Russian intellectuals doubted and questioned the “right” of the British to govern India and the “benevolence” of colonial rule. Where the West saw the “white man’s burden” of “ameliorating” the “Asiatic savages”, Russia would see oppression, destruction and humiliation of a country of great culture.

This feeling intensified during the early Soviet era. It was not by chance that a semi-literate Cossack from Sholokhov’s famous novel “Virgin Soil Upturned” learned English with a special purpose of bringing British imperialism to account “for sucking the blood of Indians.”

Belyayev was fully supportive of these views. His Ariel fully identifies himself with Indians – not with the despotic Raja, of course, but with the poor low-caste villagers in whose hovel he found hospitality, care and love. He uses mud or some plant juice to brown his skin – not only to disguise himself, but to avoid looking like a Sahib. All “white Sahibs” in the novel are disgusting, not only as oppressors and rogues, but, more importantly, because of their vehement racism and snobbish aversion to Indians -- even Jane, who displays some good qualities, is afflicted by this malady.

It is between his British identity by blood and Indian identity through emotional bonds that Ariel has to choose at the end of the novel, when the course of events reinstates him as a rich heir and member of British elite. He makes this choice unerringly. When, at a lavish reception organised by Jane to celebrate her brother’s ‘homecoming’, a certain Lord Forbes abuses Indians as “crude beasts worshipping cows”, Ariel simply explodes.

“Most of these simple and honest people are much more honourable than those present, who, by the way, live at these Indians’ expense,” Ariel says. After a grand disagreement with Jane Ariel promises to “never trouble her again” and secretly leaves their lavish mansion at night, to board a ship going to India, “in the third class, as the very thought of travelling together with people like Lord Forbes was unbearable”.

At this point Belyayev left his hero on the way to India where love and friendship beckoned him. Sadly, the writer did not live long enough to see India showing the door to the likes of Lord Forbes. He died a few years before India became independent.

Though unable to see India, Belyayev fantasised about it and conjured up the life in India in all its richness and complexity. Paradoxically, his vision, strengthened by knowledge and sympathy, shines through clearer than in some others who were fortunate to see India but, blinded by prejudice, failed to see the real people and the real place.

Eugenia Vanina, D.Sc. (History) is Chief of the History and Culture Section, Indian Studies Centre, RAS Oriental Studies Institute.

The article was first published in 2012.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox