Russian Booker winner: The Berlin Wall was never part of history

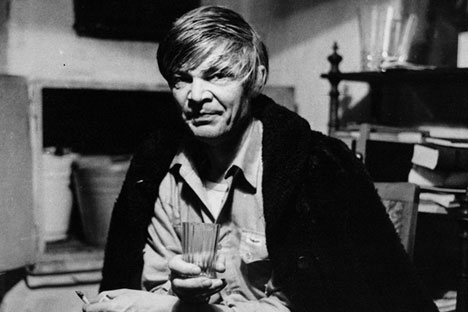

Peter Aleshkovsky, the winner of the 2016 Russian Booker prize, speaks at a press conference in Moscow.

Dmitry Serebryakov/TASSRossiyskaya Gazeta: The main character of The Fortress, archaeologist Ivan Maltsov, is writing a book about the Golden Horde and at night dreams that he is a great Mongolian warrior. Why did you resort to this device, of a novel inside a novel?

Peter Aleshkovsky: "The Mongolian chapters" are there to realize that the Berlin Wall was never part of history, like the Great Wall of China was, but everybody knows that anyway. It was erected at one point, during the Cold War, but it was such a small and insignificant bit of the history of humankind. The problem is that we are still trying – and at the moment increasingly so – to separate ourselves from other states and cultures. Other spaces were never separated from Rus. Ancient Rus, medieval Rus, Peter the Great’s Rus were always a brew of different influences and trends. We know how many foreign officials there were in Peter the Great’s court.

Do you know how many foreigners there were at the Moscow court of Kalita [Ed.: Prince Ivan I (1288-1340) ]? A lot! Apart from Rurikids [Ed.: descendants of the founder of Rus, the Varangian prince Rurik] and descendants of Gediminas [Ed.: the Grand Duke of Lithuania ], who were eliminated by Ivan the Terrible so that appanage princes were no more, so that there was no longer any blood equal to his, there were numerous Tatars who moved here [Ed. during the period in which the Mongols ruled Rus]. All those were migration processes and mixing of bloods that must have been designed by God. Yes, indeed! So that there is no degeneration, so that there is a constant refreshment of blood!RG: Your protagonist is perhaps the only person in the novel who has a conscience, yet at the same time he is the most unhappy character in the book. He makes a discovery – finds an ancient temple – but dies, is buried alive at the site of his discovery. What did he do to deserve it?

P.A.: It is, of course, also a metaphor. He dies and he wins. I would not say it is a defeat. There is a spark, a moment of touching the eternal, the truth. You know, death, a seeming defeat, may in fact be a source of strength. I recently had a meeting with readers in Murmansk [Ed.: 1,150 miles north of Moscow].

There is a dreadful monument there, at a spot where Soviet troops during World War II for two years held off the Germans, not letting them move more than two kilometers into Russian territory. There are only rocks there and thin birch trees – there is nowhere to hide. The trenches were just knee deep because it was impossible to dig deeper into the rocks. I found myself there, among those rocks, under that dark and grim sky, and there is a dark obelisk there, with thousands names written on it. That place used to be called “Valley of Death;” it is now called “Valley of Glory.” Although “Valley of Death” is a far more glorious name, and more appropriate too. Because people do know that it is a place of death. And that death makes those who were killed there into glorious heroes. So when somebody tries to put a coat of cheerful paint on it, the blood still seeps through. And there is a feeling of poignancy in that place, just as there should be in a place like that. How insensitive everything is, what “Valley of Glory”… The word does its deed, the word often breaks through. That’s what all this is about.RG: Can words and books change the world, or at least have a serious impact on it?

P.A.: No, nothing can change the world. Except that perhaps the Bible, the Koran, the Torah have changed the world, but we are speaking not about religion but about the books. A book can change a person’s life; for example, my life was changed by books. Since childhood, my life has been transformed by the word and to this day still I read every day.

R.G.: Back in 1990, Venedikt Yerofeyev, the author of Moscow–Petushki, was asked what ills were the main ones for Russia then. Hereplied…

P.A.: Perhaps you’d better not tell me and we’ll compare?

RG: What an excellent idea, let's compare!

P.A.: I think our whole conversation was about it but I shall say it once again: an incredible loss of culture, a neglect of culture.

RG: A loss in relation to something?

P.A.: Imagine a sieve, which used to be able to hold flour. Then the car set into motion, the sieve began to shake and everything began to fall through it. We keep shaking and shaking it but the end is near. The first is the loss of culture. The second – absolutely related to the first one – is the loss of science. These things are related, it is a continuation of the loss of culture. Everything else can be rectified. When culture and science are at the appropriate level, then there is accord in society, people speak the same language, there is the right understanding of the economy and of one’s position in the global world… There is a well-known maxim: history never teaches anyone anything; although it should.

And what did Yerofeyev replied to that question?

RG: Folly and incredible greediness.

P.A.: These are the same things. Culture implies quixotism, and calmness, and generosity. That is why lack of culture always equals greediness and dishonesty. It’s all about grabbing something at whatever cost. Disgusting.

This is an abridged version of the interview first published in Russian by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox