Raising homeless kids in the Soviet Union

Republic of ShKID. "The Republic SHKID". Gennady Poloka, director. A still from the film. Sergei Yursky, center

RIA NovostiThe acronym ShKID, which stands for the Dostoevsky School of Social-Labor Education, was well known to generations of Soviet children. A real orphanage that opened in September 1920, it was the setting for Grigory Belykh and Leonid Panteleev’s famous cult novel describing young homeless children who had no choice but to turn to petty crime in the turbulence of the Civil War years. Indeed, if they fail the selection process for the orphanage they have only one other fate in store: prison. What marks out the book is the fact that it was based on true events, and the authors described themselves in the work.

Real citizens

The book revolves around the state’s attempt to reeducate the young “hooligans”, and their attempts to resist this. Focusing on the efforts by Viktor Sorokin, called Vikniksor by the “Shkids”, the book explores notions of belonging and identity, as Vikniksor attempts various novel ways of creating a sense of cohesion amongst his charges.

All of the book’s protagonists are based on real people, including the book’s future authors Grigory Belykh (Grishka) and Leonid Panteleev (Lyonka). As teenagers, creative pursuits could not have been further from their minds, however. Lyonka eked out a living stealing and trading, and even participated in suppressing the Kulak (wealthy peasant) uprising, while Grishka was a general con artist who also worked as a “horse”, waiting for passengers at train stations and riding their heavy luggage across town on a sled in exchange for a loaf of bread.

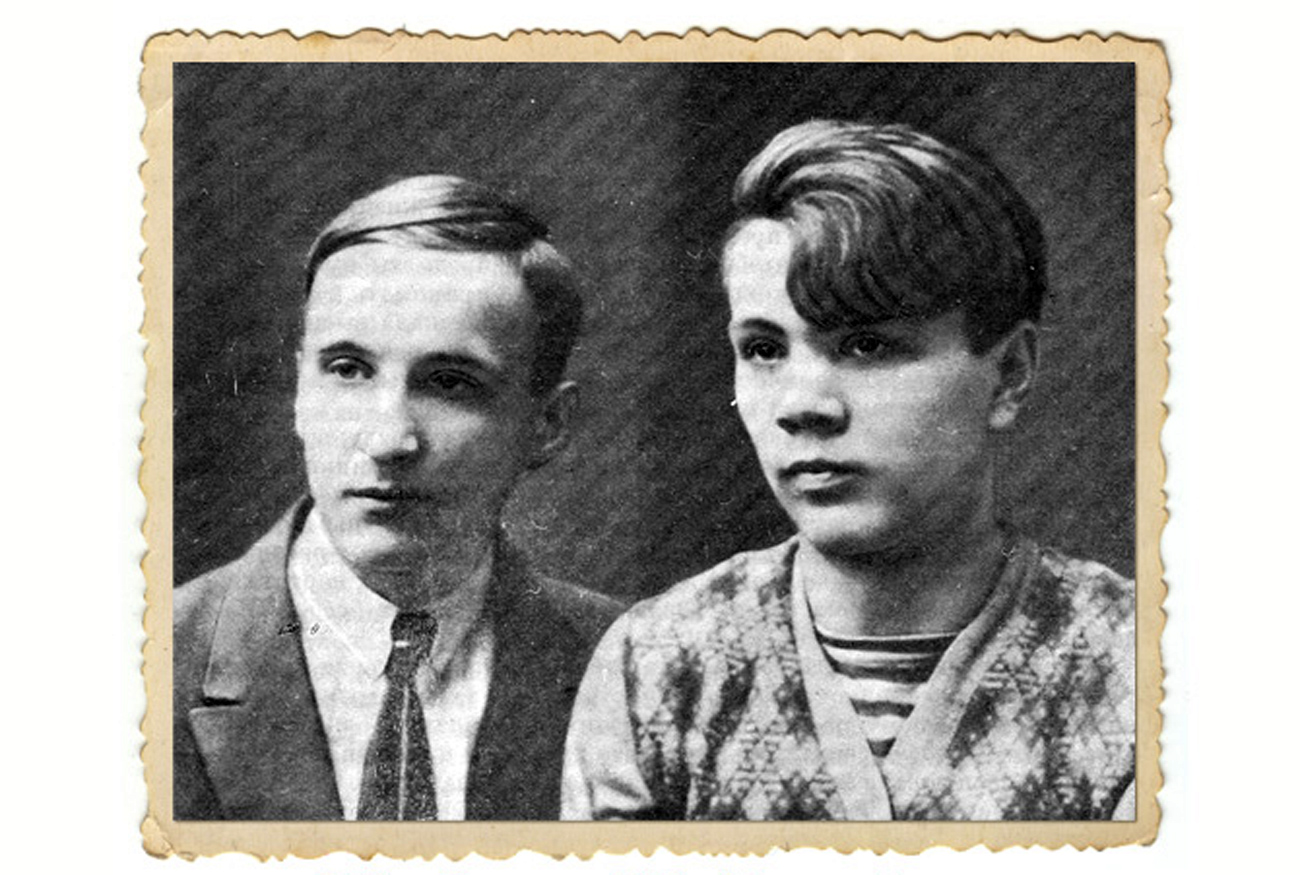

Grigory Belykh (Grishka) and Leonid Panteleev (Lyonka), 1928. / Archive photo

Grigory Belykh (Grishka) and Leonid Panteleev (Lyonka), 1928. / Archive photo

Vikniksor attempts to establish a “republic” in the school that mimics the Bolshevik ideal of society. All property and class distinctions are abolished and equality is declared. However, as the civil war rages outside, the world of the orphanage soon resembles starving Petrograd too. One teenager becomes an entrepreneur by borrowing and trading bread. He soon ingratiates himself with the older boys by giving them some of his bread reserves in exchange for protection and muscle. This continues until the other “citizens” themselves rise up against him.

The element of truth behind these teenage power games is what makes the book so fascinating. As Leonid Panteleev would later recall: “We wrote TheRepublic of ShKID in good spirits, without thinking much, just whatever came to mind… We didn’t have to create anything. We just remembered and wrote down whatever was still fresh in our boyish memory.”

Ostracism against anarchy

The school teeters on the brink of anarchy for the majority of its existence. The orphans resist the rules Vikniksor tries to impose on them and willfully steal food and anything else of value. At one point Vikniksor decides to apply a method of punishing criminals favored in Ancient Greece: ostracism. During elections, the Greeks would write the name of any citizen who threatened the state’s democracy on clay skulls. This person would then be subject to exile.

This is an important test for the Shkids, as they are all, in theory, united by the street rule of not betraying their own. However, when, fearing retribution, only a few refuse to name their fellow transgressors, it is clear that the state – as embodied by Vikniksor – is gaining the upper hand. Within the school, as in wider society, the old outlook is gradually being replaced by the new system.

A scene from 'Respublika SHKID' film. Producer by G. Poloka. Lenfilm Studios. / Photo: RIA Novosti

A scene from 'Respublika SHKID' film. Producer by G. Poloka. Lenfilm Studios. / Photo: RIA Novosti

TheRepublic of ShKID has been translated into many languages, and in 1966 a film of the same name was released, receiving many awards at Soviet festivals. The book also received the attention of the Soviet proletarian writer Maxim Gorky, who wrote about it to pupils at the Gorky colony in Kuryazh.

Mentioning his admiration for people who are dealt a difficult hand by fate and prevail, he writes: “Just recently two such individuals wrote and published an amazingly interesting book… The authors are young guys; one is 17, the other is 19, I think. They write with talent, much better than many mature authors. For me this book is a feast. It supports my idea that human beings are the most amazing, greatest phenomenon on Earth.”

Read more: The untold story: Why Stalin created a cult of Alexander Pushkin

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox