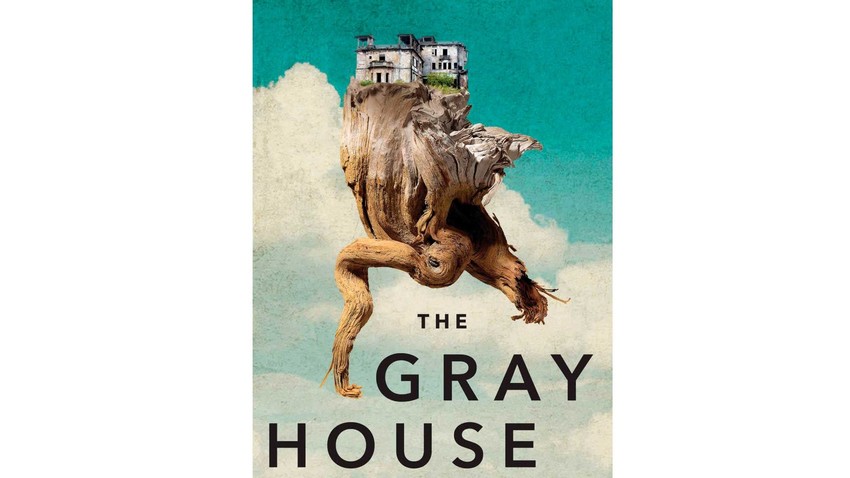

Book review: School for disabled kids becomes the site of a mystery

Mariam Petrosyan’s The Gray House was a sensation on the Russian literary scene when it was published in 2009, and in 2013 the author was included in the documentary “Russia’s Open Book: Writing in the Age of Putin”, hosted by Stephen Fry. Petrosyan was featured along with five other contemporary writers “who came from one of the world great literary traditions. And what they are doing with it is new and their own.”

Vibrant Gray House

In the mid-1990s an Armenian graphic artist called Mariam Petrosyan worked as a painter at the Soyuzmultfilm animation studio and gave friends in Moscow a manuscript of her then-unfinished novel, written in Russian. Passed lovingly from hand to hand, the book finally found its way to a publisher in 2009. The following year the novel, called The Gray House in English, won several awards and began to attract a cult following and has since inspired postgrad dissertations, Instagram pages full of fan-art and long signing queues. This year it has been published in English.

Petrosyan has refused to write a sequel or sell the film rights to this complex and unusual epic, whose 700 pages are full of vibrant characters. The Gray House is a school for students with disabilities. The teenagers use wheelchairs or prosthetics and the leader of the house is blind. There is nothing sentimental or tokenistic about these wisecracking young adults, sporting dreadlocks, tattoos and a murderball-style physicality. Different characters narrate an overlapping series of events, most of them known only by a pseudonym or “nick”.

We first experience the Gray House through the eyes of Smoker, a relative outsider, who moves from the conformist “Pheasants” dormitory to the anarchic “Fourth”. Alternating with this are flashback chapters (helpfully designated by a change of font) in which, confusingly, several people have different, earlier nicknames. Petrosyan excels at the fresh details that make up individual personalities. One inscrutable youngster likes “seltzer, stray dogs, striped awnings, round stones…” and hates “white clothing, lemons, … the scent of chamomile.”

Mariam Petrosyan. Source: Grigory Sysoyev / RIA Novosti

Mariam Petrosyan. Source: Grigory Sysoyev / RIA Novosti

The number of narrators proliferates, including the appealing figure of Tabaqui the Jackal, whose entries provide a kind of authorial manifesto: “I don’t like stories. I like moments. I like night better than

Polyphonic narrative

The novel is full of references, classical (Shakespeare, Dostoevsky) and pop-cultural (Bowie, Bruce Lee). Sometimes the varying characters of the different dormitories and the mentions of dragons and basilisks make it all feel like a Soviet version of JK Rowling’s Hogwarts. Elsewhere, there are echoes of Lord of the Flies in the rival gangs of ungovernable boys, face painting, and fires. Songs and fairy tales are all part of the textual patchwork, along with all kinds of allusions, from Hieronymus Bosch to the Kama Sutra. Repeated epigraphs from Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark confirm the influence of nonsense poetry.

Petrosyan’s stylistic quirks match her flamboyant protagonists; one gothic-sounding sentence, rich in sub-clauses, lasts a page and a half. Yuri Machkasov’s translation is a herculean feat. The slightly colorless Gray House has replaced the book’s intriguing, original title, The House, in which…, but Machkasov has captured the novel’s poetic richness. Petrosyan makes fun of some of her own metaphors – smashed watches, melting snowmen – as she investigates a series of liminal states: twilight, adolescence, the borders of sanity.

Individuality is a central theme, producing a postmodern symphony of narrative voices. "Everyone chooses his own House. It is we who make it interesting or dull…" explains a student called Sphinx. Later Sphinx tells his girlfriend (one of the novel’s relatively rare female characters): "Whoever’s telling the story creates the story. No single story can describe reality exactly the way it was."

Read more: Book Review: Is all of Russian literature a chamber pot?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox