Is all of Russian literature a chamber pot?

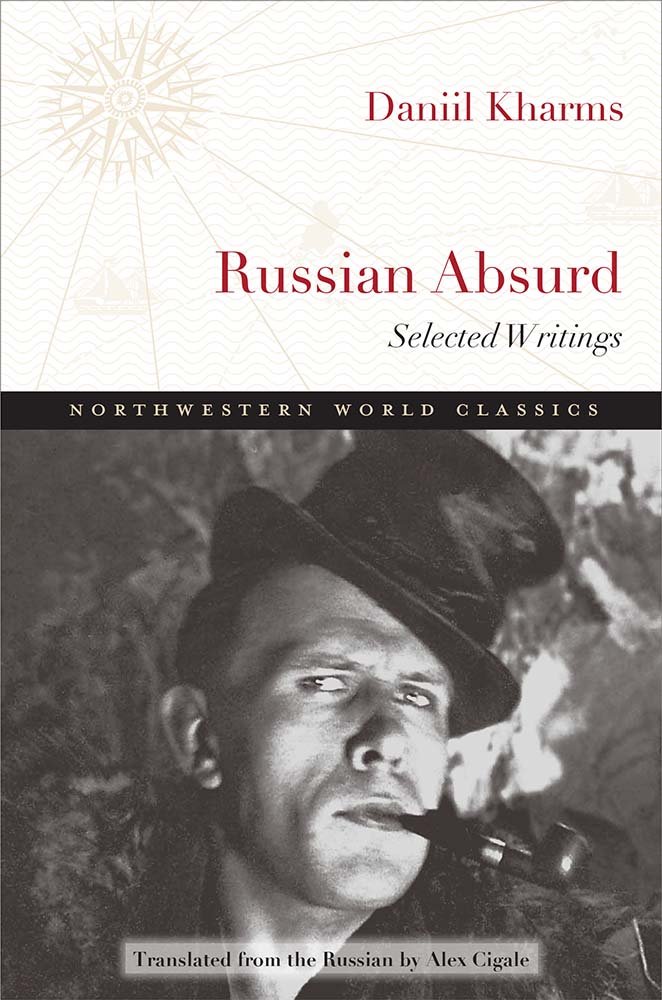

Portrait of Daniil Kharms

Tatyana Druchinina Translated by Alex Cigale; Northwestern World Classics, February 2017. Source: Amazon.com“The power that words are invested with must be liberated,” wrote Daniil Kharms in 1931. His modernist literary experiments continued to influence Soviet counterculture for decades after his untimely death.

Translated by Alex Cigale; Northwestern World Classics, February 2017. Source: Amazon.com“The power that words are invested with must be liberated,” wrote Daniil Kharms in 1931. His modernist literary experiments continued to influence Soviet counterculture for decades after his untimely death.

Kharms, whose original surname was Yuvachev, was born in 1905 and formed the absurdist OBERIU movement, together with Alexander Vvedensky. Censored, arrested and sent to a psychiatric hospital, he starved during the siege of Leningrad in 1942, and his writings survived mostly in secret manuscripts, passed from hand to hand.

Russian soul?

Translator Alex Cigale writes in his cerebral introduction to this new anthology, Russian Absurd, that Kharms’s aesthetic includes: “the ridiculous as a reaction and an alternative to revulsion and resignation before an absurd age.” Cigale sees Kharms as part of a wider generation of 20th-century existentialist writers, and hopes to help enlist him “in the canon of world literature” alongside Sartre, Beckett and Camus. Cigale also claims that: “There is something about Kharms that is emblematic of the condition of the Russian soul…” Kharms wrote in a letter, capturing the dual essence of his own work, that the Russian spirit is “always either divine, or entirely laughable.”

Bathos (a sudden shift of registers from high to low – or divine to laughable) is one of Kharms’ chief satirical tools. A prose piece from 1932 that opens “The infinite: that is the answer to all questions...” ends with the writer staring out at “cocks and hens” in the yard outside. In a poem of 1939, he writes: “I thought a long time about eagles / but confused them, I think, with flies.” The deliberate undermining of heroic images is in stark contrast with the officially sanctioned grandeur of socialist realist art in the Soviet era.

Russian literature is a chamber pot

His surrealism mixes comedy and horror, and many of his stories have a dream-like disregard for logic and causation. In “The Fate of the Professor’s Wife” a professor’s unhappy widow dreams: “Leo Tolstoy is walking towards her with a chamber pot in his hands…” Tolstoy turns into a barn, where she is trying to catch a chicken, which becomes a rabbit. But her real life is even more brutally surreal and the mounting absurdities give a strange and poignant weight to the short story’s abrupt ending.

“All of Russian literature is a chamber pot,” Kharms wrote at the end of a poem in 1936. In overturning conventional literary forms, he makes fun of 19th-century writers living in an era when traditional narratives still made sense. “The time of theatre, of grand epic poems, of beautiful architecture came to an end one hundred years ago,” he wrote in a letter of 1933.

I am the world

In his early “manifestos”, Kharms proclaims: “Our work is about to begin and it consists of registering the world…” Some of his writing evokes everyday trials: waiting for the communal bathroom, running out of cigarettes, being bitten by fleas. At other times, he obsesses over number theory or circular conversations with himself about the nature of existence: “But I am the world / But the world isn’t me”.

The relatively playful 1929 prose “rules” for “sentinels on the roof of the State Publishing House” (the sentinel is not permitted “to ride the roof’s crest as though it were a horse” or to “chase after sparrows”) have become bleak, brutal fragments by the early 1940s. A one-paragraph story called “Mob Justice” describes a pointless murder and ends: “The crowd, its lust for violence appeased, disperses”.

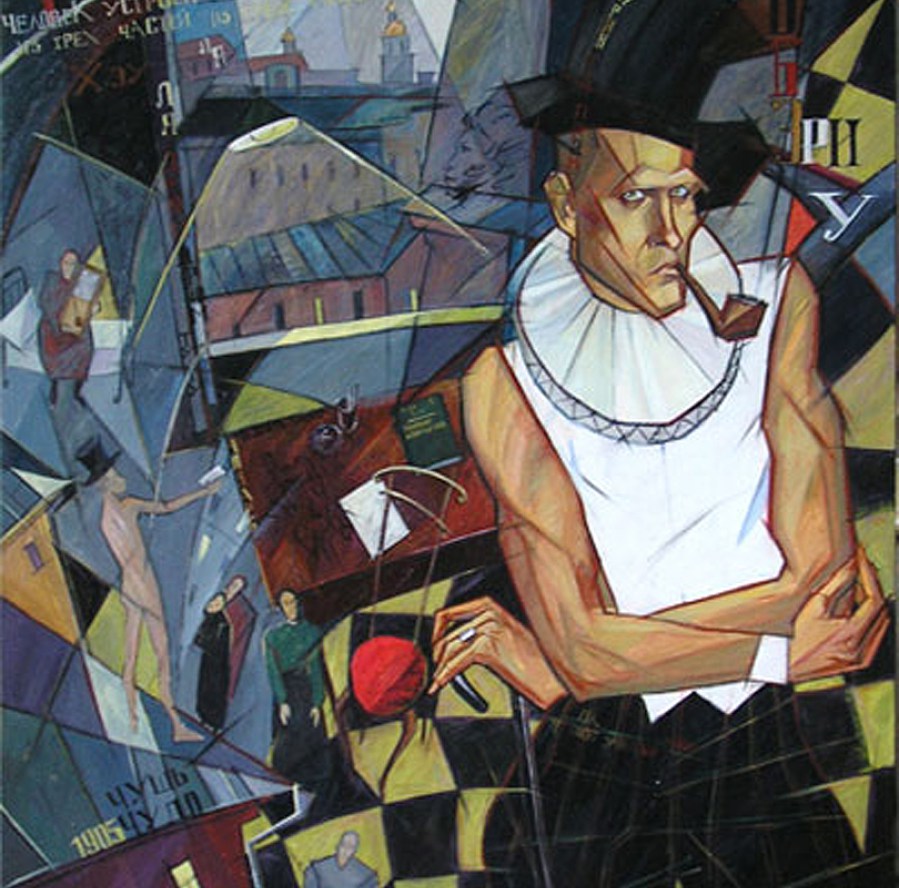

Portrait of Daniil Kharms. Source: Tatyana Druchinina

Portrait of Daniil Kharms. Source: Tatyana Druchinina

Opening his selection of prose from the last years of Kharms’s life, Cigale reproduces the author’s 1931 confession letter, extorted by the murderous Soviet security services or NKVD. This document gives the cruelty of the writing that follows its chilling context, what Cigale calls “the surreal, nightmarish quality of Soviet reality.

Ironically, there are moments of creative truthfulness in this forced fabrication. “Our trans-sense language is antithetical to the materialist purposes of Soviet artistic literature,” Kharms confesses. This anti-sense was deliberate and was indeed intended to undermine the status quo. “I find heroics, pathos, moralizing … abhorrent,” Kharms wrote in 1937. Like Vvedensky, Kharms saw “pure nonsense” as the only sensible reaction to the madness of the world around him.

Cigale has chosen a roughly chronological order for the works he includes in this illuminating selection, reflecting different periods in Kharms’ unhappy life and deteriorating mental state. Poetry is gathered in a final, 40-page coda and ranges from an un-Soviet prayer, reminiscent of Gerard Manly Hopkins, (“Unthrottle, Lord, the brakes of my inspiration”) to an ode to cunnilingus (“I’m in love with your pudenda…”). Moments of despairing lyricism intermingle with characteristic bitter jokes and glimpses of Kharms’s home city, “still unpeopled Leningrad.”

Read more: Book review: The Pirate Who Does Not Know the Value of Pi

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox