Why were Soviet adults eager to read children’s stories and poetry?

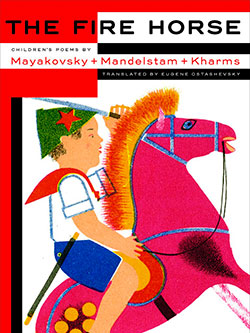

The Fire Horse: Children's Poems by Vladimir Mayakovsky, Osip Mandelstam and Daniil Kharms.

The New York Review Children’s Collection Translated by Eugene Ostashevsky. March 2017, New York Review Children’s Collection

Translated by Eugene Ostashevsky. March 2017, New York Review Children’s Collection

The Fire Horse, a newly translated collection of Soviet children’s stories, including a whimsical tale of two trams by Osip Mandelstam, bears witness to an extraordinary flowering of illustrated kids’ books in the 1920s. Mandelstam’s wife, Nadezhda, wrote in her autobiography, Hope Against Hope: “In the mid ‘twenties, the pressure got worse; … Only children went on babbling their completely human nonsense...”

Children’s rhymes with a twist

Poets like Vladimir Mayakovsky and Daniil Kharms wrote rhyming stories, in which boys pretend to be planes and toy horses are built to “help out the red cavalry”. The elegant, modern illustrations by Lidia Popova, Boris Ender and Vladimir Konasevich make these verses especially memorable.

Eugene Ostashevsky’s translations capture a similar minimalist power. As in his own poetry, Ostashevsky’s uncompromising, deceptive simplicity is stronger than a softer, more contrived and melodic version might be. “They take a walk with dignity / To the paper factory,” runs Ostashevsky’s translation of Mayakovsky’s poem about a collectively constructed rocking horse. The comfort of the child-like rhythm is deliberately undermined by the awkward half rhyme.

In Mandelstam’s 1925 story about two Leningrad trams there are moments when the translated rhythm jolts over an extra syllable like a streetcar on a misaligned track: “Winking merrily along with electricity.” The futuristic imagery may have seemed as avant-garde at the time as TS Eliot’s “patient etherized upon a table” was 10 years earlier. Boris Ender’s brilliantly spare illustrations are equally radical.

Last flowering of experimentalism

Vladimir Konasevich’s pictures from a book by Kharms called Igra are more detailed, but they also have a bold and unmistakable style. The pages are bright with symbols of an industrialized Soviet utopia: cranes and silos, steamships and streetlamps. Ostashevsky has translated the Russian title, which could also mean game or performance, as “Play”, which fits the dynamic nature of the poem. The onomatopoeic shouts of kids at play are recreated: “Roo-roo-roo” from Peter’s car, “Zoo-zoo-zoo,” from Mikey’s plane, alongside “Moo-moo-moo” from a passing cow.

Repetition, that key device in children’s literature, here serves – as often – to enhance the fun, but also to reinforce the message about powering onwards into a technological future. The three boys in Play jump, skip, hop and spring joyfully into the distance at the poem’s end, “ran so hard their heels were flashing”, loudly shouting “Roo-roo-roo.”Some of the pictures, like Lidia Popova’s 1928 illustrations for Mayakovsky’s “The Fire Horse”, are familiar from Inside the Rainbow, an earlier collection of works from this “golden age” of children’s books, published by Redstone Press. The earlier book included extracts from Lenin’s speeches, or from Soviet posters on childrearing, reinforcing – as the writer Philip Pullman observed in an introduction to Inside the Rainbow that “nothing comes without a context.”

In Russia radical constructivist experiments surrounded and followed the revolution, 100 years ago. When these books were created, innovation had not yet given way to the soullessly over-ornate neoclassicism that characterized the later Stalin era. The Fire Horse is pure kids’ poetry, with no introduction and only short biographical notes at the end. It would make a lovely gift and captures, in these colorful, relatively-context-free pages, some of the creativity of the Russian avant-garde.

VIDEO: Live Classics: Foreign kids quoting Russian literature

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox