Tales from Earth’s edge: Globetrotting for love on Sakhalin Island

Sakhalin was home to Russia’s largest penal colony, and Chekhov called it "hell." On 19th century Sakhalin, the famous writer encountered lice and bedbugs, starvation, suicide, floggings and forced prostitution, but also found time to describe the velvety grass and salty sea mists.

Sakhalin was home to Russia’s largest penal colony, and Chekhov called it "hell." On 19th century Sakhalin, the famous writer encountered lice and bedbugs, starvation, suicide, floggings and forced prostitution, but also found time to describe the velvety grass and salty sea mists.

More than a century later, RBTH’s Guest Editor for Asia Ajay Kamalakaran repeated Chekhov’s journey and tried to depict the island that balances between negative aspects of modern life (poor roads, bureaucracy, corruption, cold), and the fleeting moments of happiness and beauty.

Millions of barrels of oil

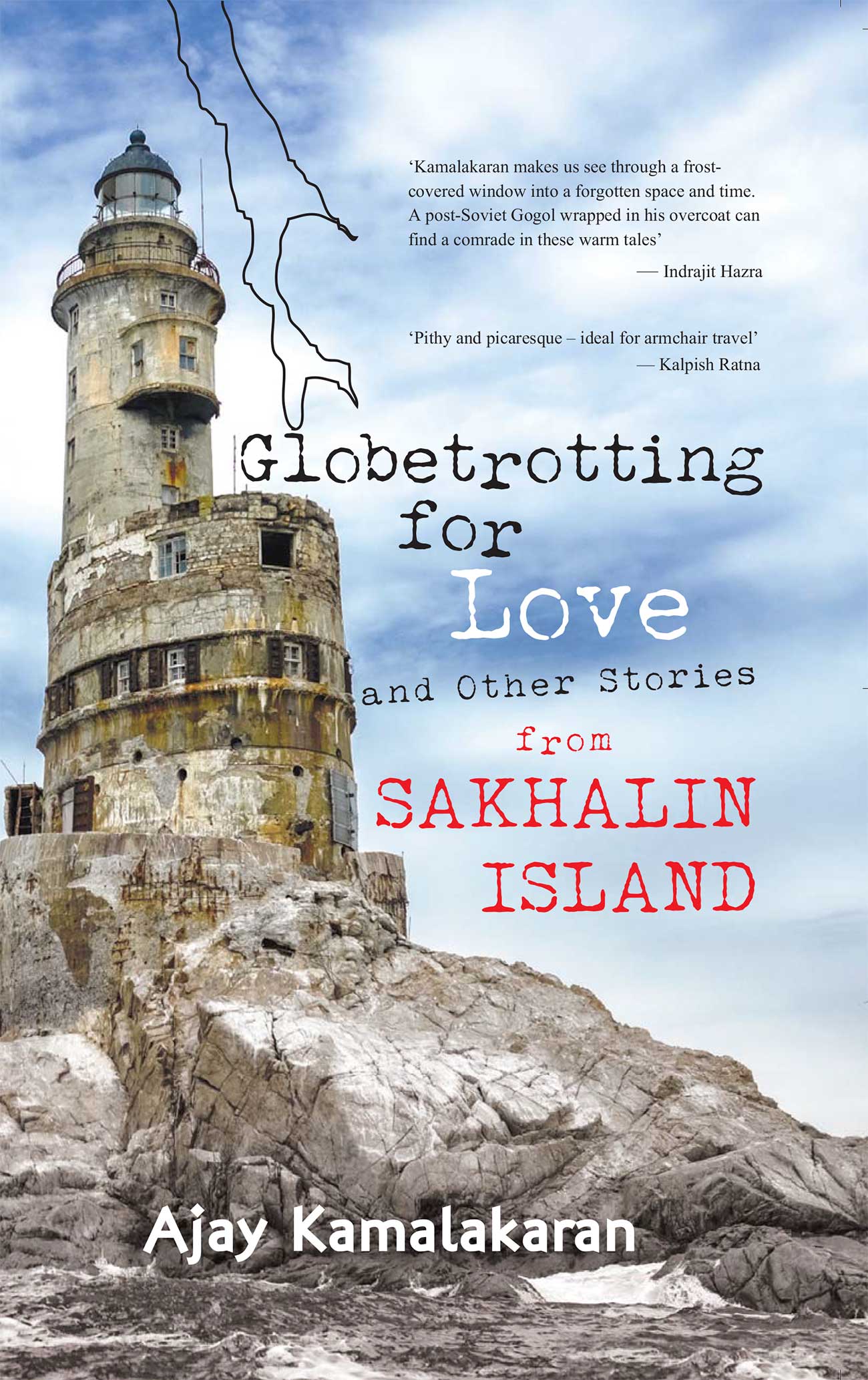

Kamalakaran edited the Sakhalin Times from 2003 to 2007, and has now written Globetrotting for Love (and other tales from Sakhalin Island) – 11 stories, which are mostly set on the island during those heady years.

Since Perestroika, Sakhalin has seen waves of prospectors looking for oil and other resources. No longer a penal colony, but an island “with millions of barrels of crude oil on its shelf,” Sakhalin is now a magnet for all kinds of entrepreneurs.

Ajay Kamalakaran. Source: Personal archive

Ajay Kamalakaran. Source: Personal archive

Like Chekhov, Kamalakaran is a great observer of the island’s personalities, their unpredictable life stories and their sometimes whimsical settings: a young man on a late evening stroll around a lake with the sound of distant church bells; or a disgruntled cleaning lady, regretting the end of the Soviet era and resenting the influx of overpaid foreigners.

One story imagines a stand-off between a ruthless, eccentric Londoner who is planning to use the beautiful locals as advertising models, and a young publisher, Andrei Klimov, who has set up a magazine catering to Sakhalin’s growing expat community.

The Londoner’s slightly implausible dialogue is peppered with “young chap” and “good heavens,” as well as the transatlantic-sounding “mighty kind” and “sure was.”

Diverse worlds

Linda from a Birmingham housing estate is another English character; “most middle-class Britons,” Kamalakaran insists, dreamed of an expat life in the mid-2000s because “waves of immigration caused a fall in living standards and public services in Blighty.”

Stories of muggings told by expat wives living in Sakhalin’s gated communities don’t bother Linda since “she never felt safe after it got dark in Birmingham either.” In Sakhalin, she enjoys the best of the diverse worlds on offer, including heavy-drinking Russian parties.

The story is ironically entitled “Gastarbeiter,” the German word for a foreigner with a temporary work permit. Linda is running a successful business, but overstays her visa. She is horrified when the judge equates her with “the millions of unskilled laborers from the former Soviet republics who live illegally in Russia.”

Magical island

A monolog called “April” starts with a series of rhetorical questions: “Can this really be spring? Where is the green grass?” Kamalakaran mentions traditional festivals: the Maslenitsa ritual that was “supposed to bring in warmth” or International Women’s Day with “gifts and toasts to our beloved women, the most beautiful on earth.”

The author contrasts summertime lake swimming with vivid descriptions of the cold; the “bone-chilling breeze” slaps one narrator “like a scorned ex-girlfriend.” Besides the psychological effects of a lack of sunlight, vitamin D deficiency, and the possibility of being stabbed by falling icicles, his narrator dreams of warmer days: “When it’s spring, I would be one of the first to climb up and scale the Chekhov Peak.”The stories often explore interesting cultural clashes and divisions. One story, tellingly titled “The Motherland,” centers on a basketball-playing office worker called Vladimir Kim. “Like many of his fellow third-generation immigrants,” Kamalakaran writes that Kim has “a Korean physique but a Russian mind.”

He calls Korean students “stupid foreigners,” and when he relocates to Seoul (which “unlike Sakhalin, had its foot firmly in the 21st century”), his Korean colleagues call him a “lazy Russian.”

Kim’s story ends with a vodka toast on the shores of the Pacific Ocean, a toast to Sakhalin, his home: “the magical island that always brings back its children.”

Globetrotting for Love (and other tales from Sakhalin Island) is being published by Times Group Books (India) and can be pre-ordered here.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox