When literature is in exile: Russian Émigré Short Stories

Dmitry Belyukin. White Russia. The Exodus.

Open sources Dmitry Belyukin. White Russia. The Exodus. Source: Open sources

Dmitry Belyukin. White Russia. The Exodus. Source: Open sources

One hundred years ago the Russian Revolution forced many writers into exile, primarily settling in Paris or Berlin, where they wrote some of the 20th-century’s finest literary works. Censored by Soviet Russia, and sometimes not well-known abroad, they are now published in English to the delight of book lovers around the world. Bryan Karetnyk has edited (and translated much of) this fine selection titled, Russian Émigré Short Storiesfrom Bunin to Yanovsky.

Russia lives on here

Evacuated from Crimea with the defeated White Army in 1920, Lukash evokes not only the landscapes of sun-drenched Gallipoli but also the hopes of thousands of young Russians living there: “men radiant in spirit, having condemned themselves to blood and heroic deeds.” Lukash sees them as archetypal soldiers, comparing them to the “powdered guardsmen of Empress Elizabeth,” as they sit around campfires talking softly “throughout the blue evening.”

“Russia lives on here,” a moist-eyed general tells the narrator. Lukash packs a world of passionate, sighing patriotism into this brief evocation of the starry mists of Gallipoli, under the gaze of “mournful angels with wings as dark as sorrow.” He even manages to transform the aging general’s despairing alcoholism into something tenderly poetic: “he’ll never refuse another glass of rough red wine or cinnamon-perfumed amber cognac.”

Visiting the museum

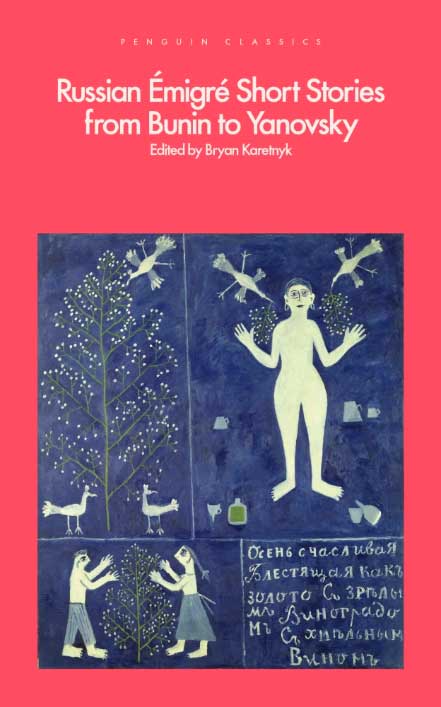

Russian Émigré Short Stories from Bunin to Yanovsky. Source: Penguin Classics

Russian Émigré Short Stories from Bunin to Yanovsky. Source: Penguin Classics

Vladimir Nabokov mocks the émigré tendency towards nostalgia with his perplexing 1938 story, “The Visit to the Museum.” The misanthropic narrator is trying to buy a portrait of his friend’s Russian grandfather from a provincial French museum. The dusty collections are brilliantly evoked: stuffed owls and porous fossils, “a pale worm in clouded alcohol” and a large sarcophagus “like a dirty bathtub.”

No sooner does the narrator get close to completing his mission than the museum corridors, which have become mysteriously crowded and labyrinthine, morph into St. Petersburg’s snowy streets: “not the Russia I remembered, but today’s actual Russia… hopelessly, my own native land.”

When Esquire magazine first published Dmitri Nabokov’s translation of this short story in 1963, they added a clarifying subtitle: “The exile's lament confuses Time (the beloved past) with Space (the forbidden homeland).” The museum is an image of the expat ability to preserve de-contextualized, out-dated memories like treasured artifacts.

Comedy and Elegy

Several writers fight tragedy with humor, turning horrifying absurdities into fertile satire. With her characteristic ear for cadence and comedy, Teffi couches her rules for new refugees in faux-Biblical language: “Thou shalt not covet they neighbor’s visa, nor his cabin, nor his currency.”

Less well known, Sasha Chorny’s amusing, “Spindelshanks,” translated by Maria Bloshteyn, depicts an émigré husband upset by his curvy wife’s new fashionable slimness. He remembers: “what my Natasha used to look like back in Narva,” and compares the convivial, symbolically ample delights of home with the colder, “sparrow-sized” portions of his new life.

Ivan Shmelyov captures the painful ambivalence of émigré life in his bittersweet story, “Russie.” The narrator is lying in a French wood, dreaming of sunny Russian birch forests, when he overhears a group of vapid English tourists and a venal local businessman talking about his native land: “Drunkards, savage peasants, Cossacks…” He says nothing. What can he say, who himself “had fled from there”? But the contrast is clear – between the cultured idyll of his memories and the Russia these foreigners think they know, “this country of eternal winter and darkness.”

Accepting permanent, often impoverished, exile is an erratic process. Behind each of Gazdanov’s wanderers in “Requiem” are difficult lives and “huge distances … traversed on foot.” The title refers to the funeral service that an elderly priest and makeshift choir sing for a dead compatriot, but also hints at an elegy for their homeland.

Afterwards, they go out into the icy darkness of Paris, “uttering foreign words in a foreign tongue, not knowing where we were headed, having forgotten whence we had come.”

Read more: Who were the Soviet dissidents?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox