IRA Triangle: India-Russia ties and America

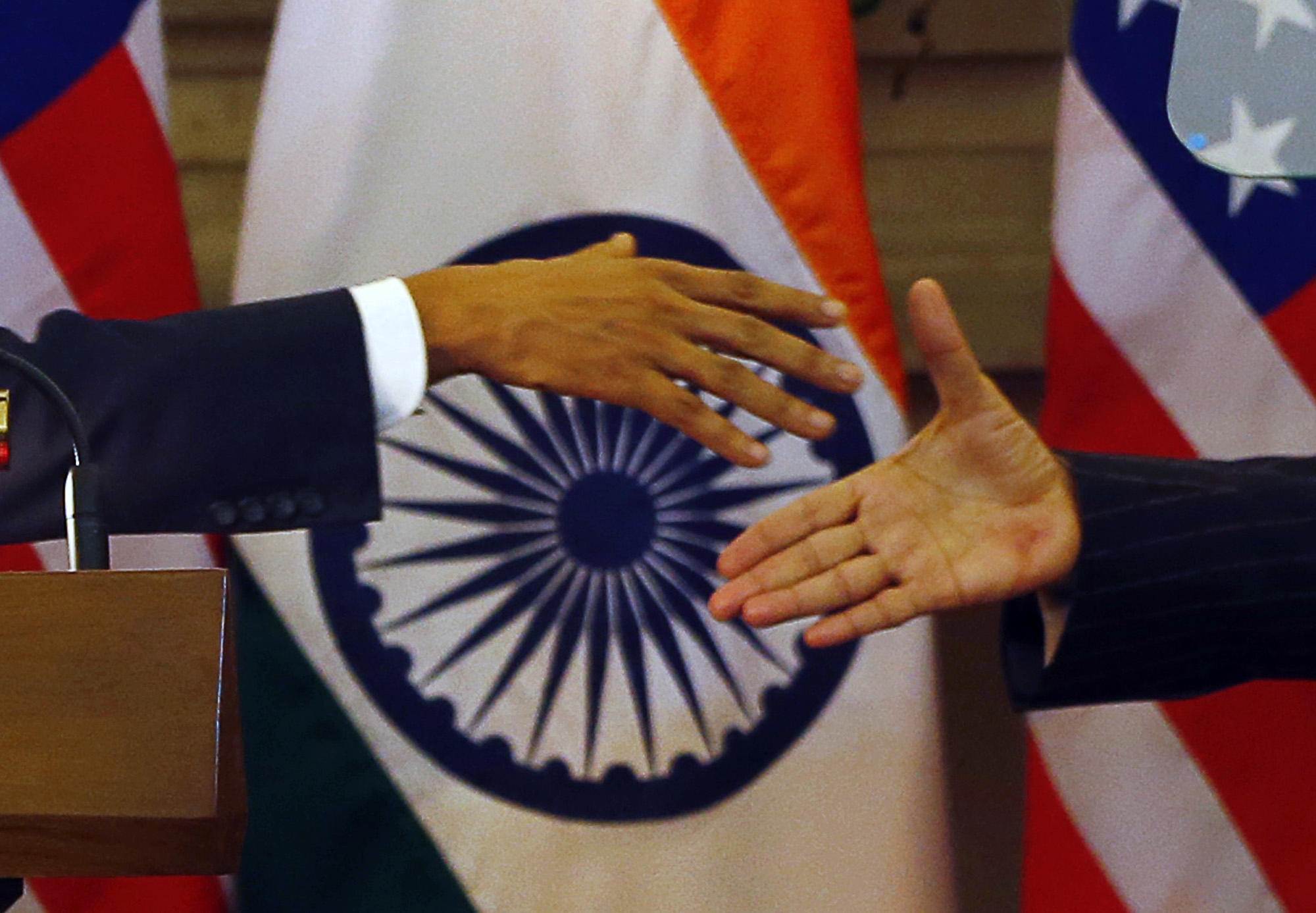

U.S. Defence Secretary Ash Carter (L) and Indian Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar address a joint news conference in New Delhi on April 12, 2016.

APThe impression gaining ground in India is that after the signing of the Logistics Support Agreement (LSA), New Delhi and Washington will soon become close allies. There is also a feeling among a growing section of people that India and Russia are drifting apart. The fact is that these are just rumours without substance, but like in all rumours there is a kernel of truth.

India and the US are coming together, but the glue is not strategic. During the 1991 Gulf War, American C-141 military aircraft were refuelling in Mumbai at the rate of two a day. No strategic realignment of ties came off that.

If there’s any glue, it’s economic. The Narendra Modi government wants to emulate China’s grand opening of 1971 when Beijing declared that it didn’t matter what colour the cat was as long as it caught mice. This policy proved to be a windfall for Beijing as it opened the floodgates to American outsourcing.

However, India must never forget it is the US that needs India more than India needs the US. So India should extract maximum concessions in return for opening up its market to the US. Here’s a short and reasonable wish list.

One, India must acquire high-end US defence technology and not just screwdriver technology.

Two, Washington must open its doors to more Indian engineers, doctors and other skilled category professionals.

Three, the US must downgrade its ties with Pakistan and quicken its disintegration.

Four, the US must not come in India’s way to play a more prominent role in Afghanistan.

Expedite MTCR membership so India can legally acquire Russian technology for missiles with a range over 300 km.

If India can get these boxes ticked, then it’s a win - win for both. If not, then India would be the loser.

Old habits die hard

According to some observers, one of the spinoffs of the LSA is that it will give India leverage in the US. But this is being overly optimistic. Take the India-US nuclear deal of 2005. Has the US built even a single nuclear plant in India? In the meantime, Russia has built two units at Kudankulam and plans to build several more. Clearly, there is more substance in India-Russia relations than in India-US ties.

It seems like a case of the more things change, the more they remain the same. Here’s how US Congressman Peter Olson would like to bring India’s economic policy in line with America’s: “As a nation, we should handle India like my dad did when I was growing up and made his blood boil. He put his arm around me and or pulled me where he would go, to make sure his fingers were resting firmly on my shoulder just to inflict some pain if I diverted from the course we would go down. That’s what we should do with their government."

Congresswoman Marsha Blackburn adds that India’s “abusive practices...are killing jobs of millions of hardworking Americans”.

This anti-Indian rhetoric isn’t new; it’s just old whine in new bottles. India-US ties got off to a bad start in the backdrop of the Cold War when Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru failed to develop a rapport with the Americans.

Former US diplomat Dennis Kux writes about Nehru in India and the United States: Estranged Democracies (1992): “The Indian leader had a considerable bias that seemed to combine the anti-American social prejudices of the British elite and the anti-American policy views of the left-wing of the British Labour Party.”

When Nehru visited the US in 1949, one particular incident caused considerable bitterness. American historian Robert Beisner writes in Dean Acheson: A Life in the Cold War (2006) that a White House secretary pointed towards Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi, mocking “these foreigners who come over here and take our money away from us”.

India was also put off by the importance given in the US to supremacists such as secretary of state John Foster Dulles, who advocated the creation of a purer white race through genetic research.

Annoyed by the warm welcome given in 1950 to Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, Nehru wrote to his sister Vijaylakshmi Pandit who was then Indian ambassador in Washington: “The Americans are either very naive or singularly lacking in intelligence. They go through the same routine whether it is Nehru or Liaquat Ali. It does appear that there is a concerted attempt to build up Pakistan and build down, if I may say, India. It surprises me how immature in their political thinking the Americans are! In their dealings with Asia, they show a lack of understanding, which is surprising.”

The Americans on the other hand thought Nehru was too full of himself. Secretary of state Dean Acheson wrote: “He was so important to India’s survival and India’s survival so important to all of us that if he did not exist — as Voltaire said of God — he would have to be invented. Nevertheless, he was one of the most difficult men I have ever had to deal with.”

Managing China

Since the early 1990s when India opened up to the world, starry-eyed Washington think-tanks have hyped up India’s potential as a force multiplier on the US chessboard. Mostly they prescribe a transactional relationship where the US helps India grow into a global power on the condition New Delhi helps the US to “manage” China’s rise. This is exactly what the warlords in Washington have offered the likes of Ukraine, Poland and the Baltic countries for “countering” Russia. The problem with this view is that it implies the US has very little use for India if not as a bulwark against Beijing.

But since 2012, when India started aiming its Agni-V nuclear missiles at downtown Beijing, the Chinese have started talking about India-China “being the most important partnership of the 21st century”. Once more of India’s ballistic missile submarines and nuclear-armed mountain divisions become operational, Beijing will come to the negotiating table. India doesn’t need the US to “manage” China.

According to Wang Jisi, dean of the School of International Studies, Peking University, after decades of trying to contain India and having failed, China now wants a reset with India. Plus, the rise of Islamic terror in China through Uighurs trained in Pakistan has got the Chinese thinking. The communists have realised belatedly that the Faustian bargain they struck with Islamabad is coming to haunt them.

“We have to fend off extreme Islamic terrorism from getting into China from Pakistan,” says Wang.

Reality check with Russia

Whether India-US ties move up or sideways, it does not mean downgrading of ties with Russia, which remains a strategic partner. India and Russia initially came together because of mutual need; New Delhi wanted quality weapons at a good price and Moscow was seeking a respectable friend in Asia; but the relationship has since grown organically.

When Russia was facing economic collapse in the early 1990s, India settled terms of its rupee debt generously in Russia’s favour. There was criticism in the Indian media as the settlement made no economic sense for India, but it was bailing out a friend who was in dire straits.

Moscow has in turn helped India by offering the crown jewels of its military industrial complex such as the Sukhoi Su-30MKI jet fighter, which raised the bar for all Sukhois globally, and providing help in building nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers. More importantly, the military assistance came without restrictive end-user monitoring agreements.

Moscow is also set to play a key role in India’s energy security. Besides cooperation in the areas of nuclear power, India is buying stakes in key oil and gas fields in Russia. Gas pipelines are in the works.

The bonhomie of the Indo-Soviet days lives on in the hearts and minds of people in both countries. Where ties were once close, and emotional, today they are based on realpolitik: India and Russia do not have divergent geopolitical goals.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox