Private sector participation key to boosting India-Russia trade

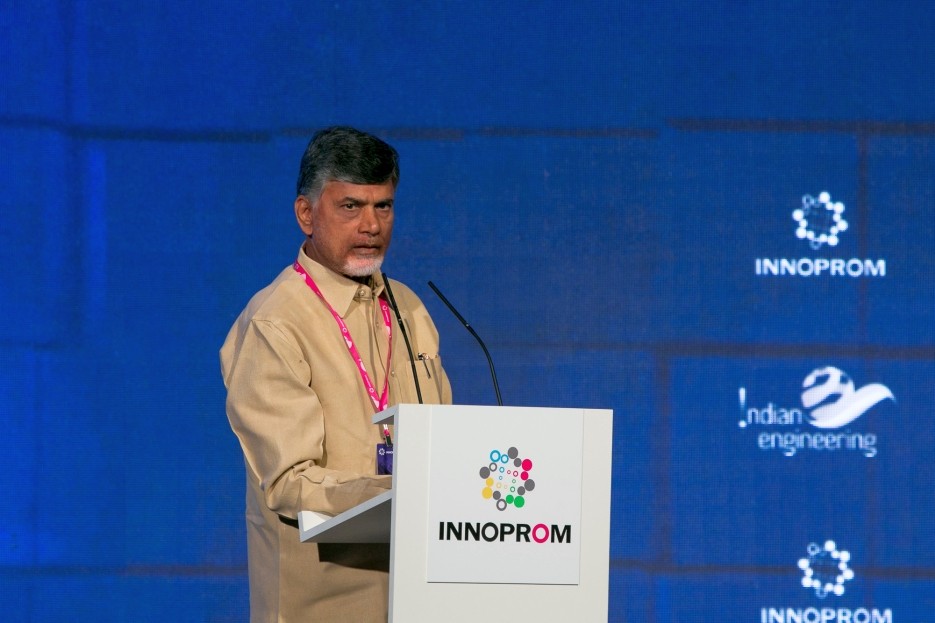

India's Micromax has managed to succeed in the competitive Russian market. Source: Getty Images

Annual bilateral trade turnover between India and Russia hovers around $7 billion. It peaked in 2012 at $11 billion and has fallen over the last few years. This of course, should be seen in the wider context of Russia’s trade turnover with all of its major partners. Moscow’s trade turnover with Beijing has fallen drastically over the same period. In 2014 it neared $100 billion but have since fallen by well over 30 per cent. The same goes for Moscow’s trade with other countries that don’t support the U.S.-imposed sanctions on Russia.

So-called experts and retired diplomats widely blame the respective governments for lack of a proper policy to boost bilateral trade between India and Russia, but such criticism is not entirely fair. Both countries have tried to push across major economic cooperation projects involving either large state-owned entities or major private corporations. This has yielded in mixed results.

On the one hand, there are success stories like the Rosneft-Essar deal, which amounts to the largest ever foreign direct investment ever made in India. But then there are also projects that have not had much luck. Take for instance, the case of Kamaz, Russia’s largest truck producer. It’s partnership with Vectra Motors failed to achieve the desired results, and for the last few months, there were reports of a tie-up with Gujarat-based AMW Motors. Sources close to the company say that the deal has fallen through and that Kamaz is now looking for a tie-up with Mahindra. They say that the company, which has faced all sorts of difficulties in India, including labour problems, is still very eager to make its Indian venture a success.

ONGC has had a few successes in Russia, including the Sakhalin-1 project, but also made some questionable investments such as its $2.9 billion acquisition of Imperial Energy. The company, which operates in western Siberia, produces less than 20,000 barrels of oil per day, compared to a target of 35,000 to 80,000.

Russian private investors have bought into India’s e-commerce boom but few other sectors seem to have grabbed their attention.

Indian companies with a focused Russia strategy have managed to meet with success in the country. Take the case of smartphone vendor Micromax, which is a top-5 brand in Russia. Other companies that have managed to achieve a good degree of success in Russia include Himalaya Herbals, which has given the country a taste of ayurveda.

Shifting the focus away from Delhi

Over the last few years, there have been leaks to the media about the two countries discussing grandiose plans in areas ranging from joint manufacturing of passenger aircraft to Russian participation in concepts such as industrial corridors and smart cities. Precious little has come to fruition from this, the main reason being that projects that involve the bureaucracies of both countries are bound to dragged down by red tape.

The key to boosting bilateral trade between Russia and India is shift the focus as much as possible to the private sector, away from the corridors of power in Delhi.

It’s a matter of great annoyance for businessmen and tourists alike that there are no direct flights between Mumbai and Moscow! Given the rapid increase in visitors from western India to Russia (and vice versa), the Gulf carriers are raking in handsome profits.

Of course, it’s going to take more than better flight connections to improve bilateral trade. Despite pre-election promises of minimum government and maximum governance, India is in 130th place in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Ranking! (The sole bright spot was in getting electricity, where India has moved up to 26th place from 51st)

Russia, on the other hand, has consistently improved and got the 36th overall rank in 2016, although it felt to 40th place this year. This may explain why more Indian private sector operators are able to achieve success in Russia than the other way around.

Private sector entities, which are driven entirely by a profit motive, will only enter foreign markets with reasonably good infrastructure and less bureaucratic hurdles. There is a visible trend of Indian businesses heading to Russia, and India will be the guest country at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in June. But for bilateral trade to meet potential, there should some real incentive for Russian businesses to enter the Indian market.

India still has a lot of use for Russian high technology, security systems and manufactured goods, such as agricultural equipment. If Russian companies can be roped in, especially in the latter segment, under Make in India, this would be a win-win situation.

A boom in private sector cooperation between would undoubtedly lead to unprecedented bilateral trade figures between the countries. In the meantime, we should also see some of the grandiose government-backed projects coming into fruition.

Ajay Kamalakaran is RBTH’s Consulting Editor for Asia. Read more of his articles here. Follow Ajay on Twitter and Quora.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox