Can you speak any of the Russian language’s hybrid 'children'?

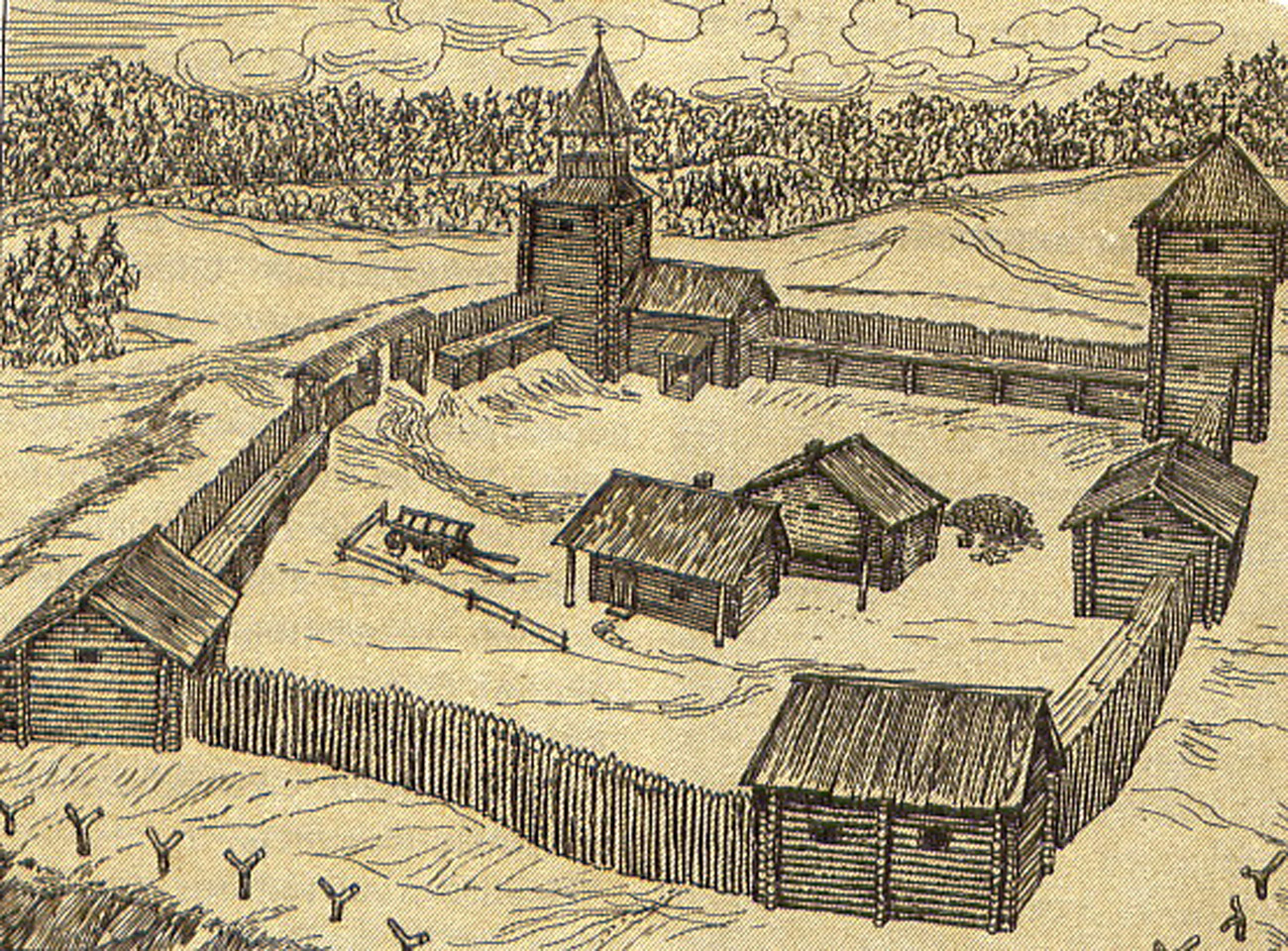

Drawing by Varvara Grankova

Many young people today know of the existence of popular hybrid languages, for instance, the African American Vernacular, thanks to popular culture.

"Take Black people from Africa, who were brought to America. They gradually learned a language mixed with their native one. This is how a pidgin language is born – a language of the marketplace," explained Alexander Volkov, professor at Moscow State Lomonosov University.

As a rule, the native speaker of a standard language finds such a mixture to sound funny. Russian also has its humorous versions, for example, hybrids with Chinese, Ukrainian, Belarusian and even Norwegian.

Kyakhta: Russian plus Chinese

Kyakhta is a pidgin language based on Russian and Chinese that existed at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries in the Amur, Manchuria and Trans-Baikal regions bordering China. The name derives from the town of Kyakhta in Buryatia.Today, linguists classify Kyakhta as "possibly extinct" – it ceased to be widely used in the first half of the 20th century. But even in the 1990s one could meet elderly Chinese traders at markets near Ulan Bator who communicated in this language. In China, Kyakhta was taught for for the benefit of officials trading with Russia.

Surzhyk: Russian + Ukrainian

The name surzhyk originates from bread made from mixed-grain flour. The status of this language is difficult to define: it’s a blend of Russian and Ukrainian that is different from both pure Ukrainian and the colloquial Ukrainian Russian. Surzhyk cannot be described as pidgin either because harmonious contact between two closely-related languages cannot give rise to a pidgin language.

Most of Surzhyk’s vocabulary comes from Russian, while most of its grammar and pronunciation comes from Ukrainian. Surzhyk appeared among the rural population, and its written form was recorded by the first author who wrote in colloquial Ukrainian, Ivan Kotliarevsky, in his classic work of Ukrainian literature, Natalka Poltavka (1819).

Nowadays, Surzhyk is common in Ukraine, especially in areas adjoining Russia and Moldova. According to the Kiev International Institute of Sociology, as of 2003 between 11 and 18 percent of Ukraine’s population communicated in Surzhyk.

Trasianka: Russian plus Belarusian

Like Surzhyk, the name Trasianka reflects the very essence of this hybrid language - in this case, a mixture of Russian and Belarusian. Translated from Belarusian, the word trasianka literally means "low quality hay" – what you get when peasants mix straw with hay. Like Surzhyk, Trasianka cannot be described as a pidgin language.

Nowadays, linguists classify it as a chaotic and spontaneous form of mixing languages. In the vocabulary and morphosyntax of Trasianka, Russian elements and features unequivocally predominate. Trasianka has its origins in the changes that took place in Soviet Belarus after World War II, (in some areas before the War). The industrialization of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR) led to a massive labor migration from villages to cities and towns.At the same time, ethnic Russians from other parts of the USSR migrated to the BSSR where they took senior positions in the Communist Party and at industrial enterprises. Former villagers, native speakers of the Belarusian language, were forced to adapt to the Russian-speaking environment, something in which they did not always fully succeed.

According to 2009 data, 16.1 percent of the Belarusian population speaks Trasianka, and it is common among Belarusians of different ages and levels of education.

Russenorsk: Russian plus Norwegian

Russenorsk, which existed in the 18th-20th centuries, was a pidgin language. Today, it’s still spoken on the Spitsbergen (Svalbard) archipelago. It arose to help Russian and Norwegian traders communicate when they traded grain and fish on the north coast of Norway.

Russenorsk contained about 400 words, and has one interesting feature that demonstrates the equality of Russians and Norwegians as trading partners. In most hybrid languages one of the languages has a dominant role, but in the case of Russenorsk, the number of Russian and Norwegian words is about the same.

Russenorsk took a long time to develop into the form that survives today. Examples of some words go back to the end of the 18th century. As trade grew, merchants started learning Russian and by the mid-19th century Russenorsk was regarded as "bad Russian" rather than a separate language. The language disappeared with the end of free movement between the two countries following the 1917 Revolution.

Read more: 7 aphorisms that are essential to understanding Russian civilization

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox