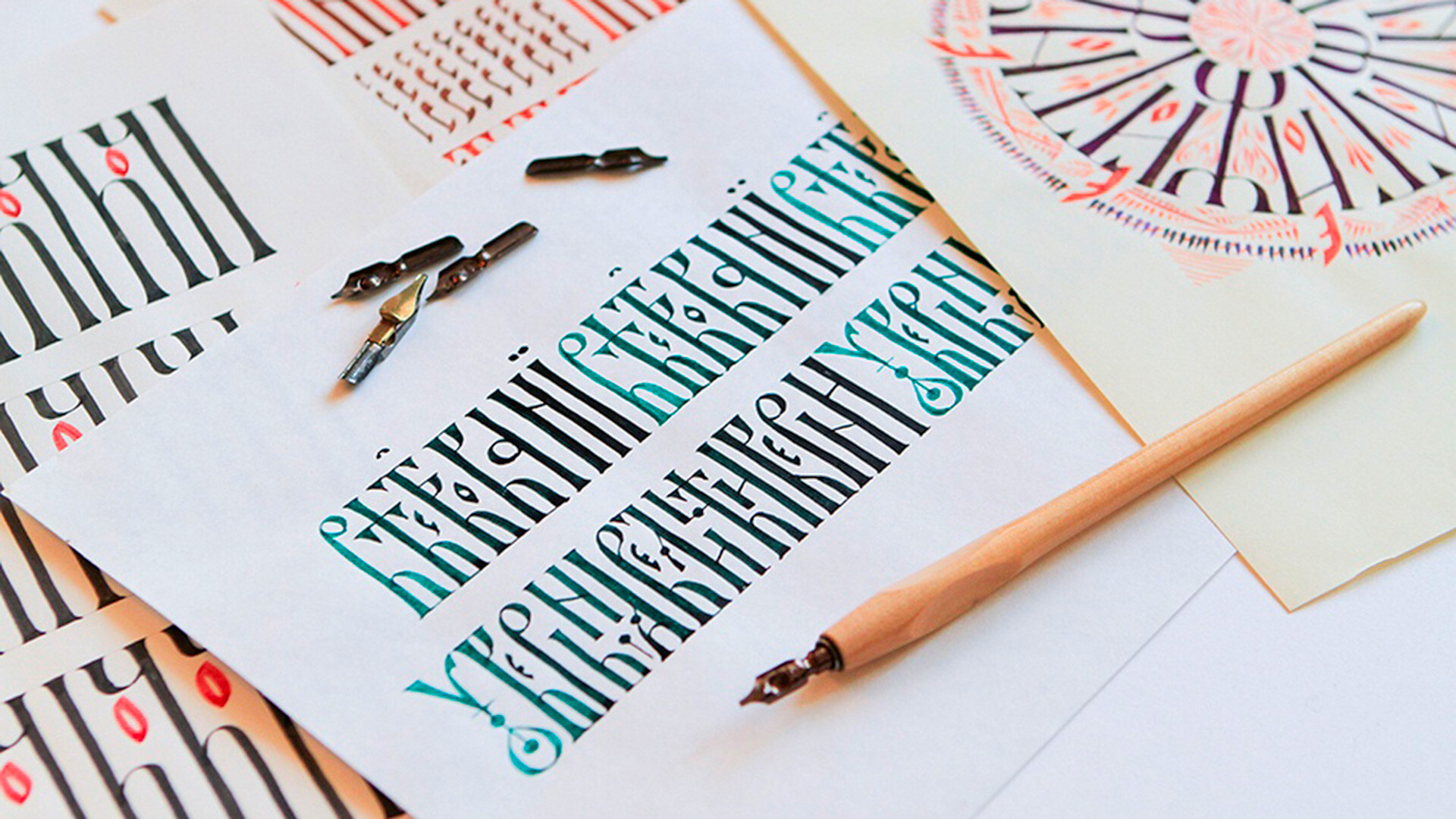

A “calligraphy tunnel” appeared in Yaroslavl in 2019: Artists Alexander Abrosimov and Evgeny Fakhrutdinov painted lines of Joseph Brodsky’s verse on the arch of a residential building using the Russian vyaz lettering. The calligraphy art object, the largest such object in the city, demonstrates that this very Russian lettering can look at home not only in the decoration of Orthodox churches, but also in street art.

Among the advantages of vyaz are simplicity of execution and intelligibility (compared with more complex types of script like cursive), as well as a balance between informative and design functions.

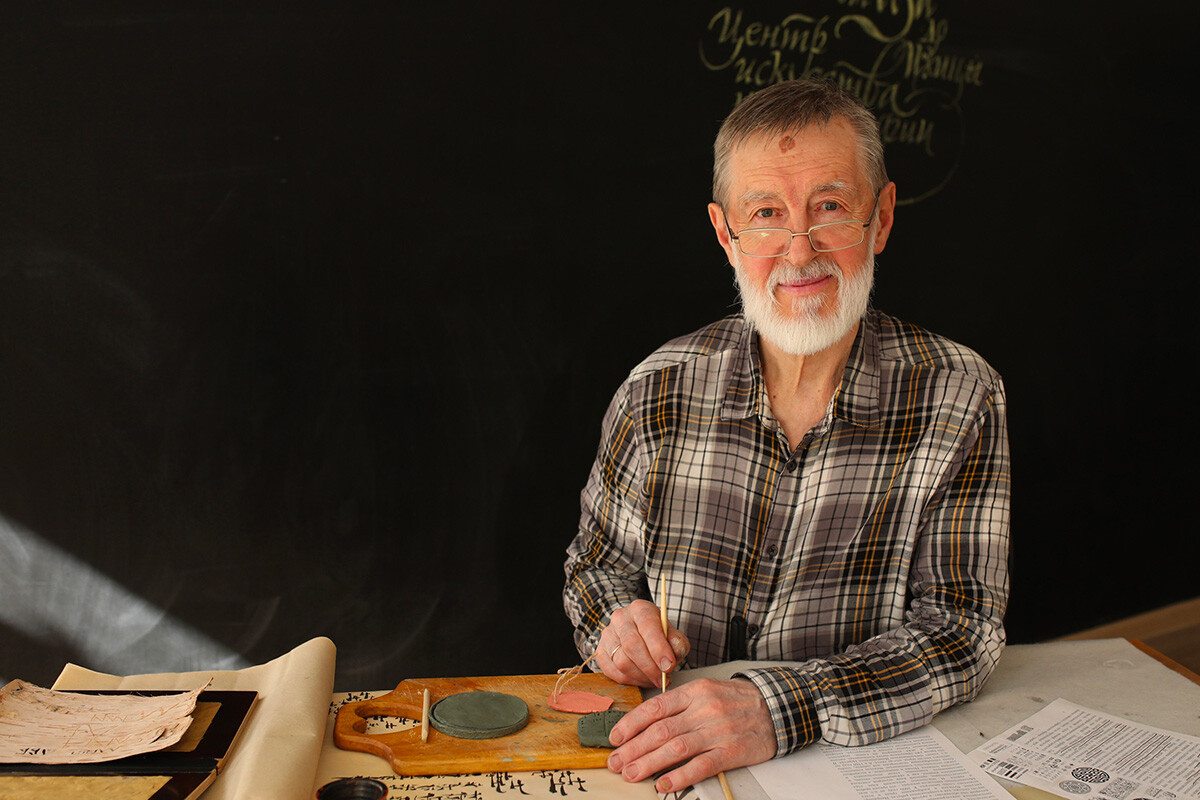

In old Russia, vyaz was used as a method of teaching elementary reading, writing and arithmetic (at that time, numbers were denoted by letters) and as the initial stage of understanding all types of written Russian, according to Pyotr Chobitko, founder and artistic director of the St. Petersburg ‘From Az to Izhitsa’ School of Calligraphy.

Pyotr Chobitko.

‘From Az to Izhitsa’ School of CalligraphyVyaz can also help foreigners in their study of written Russian. Nationals of Canada, Germany, Poland, Cyprus, Finland, Britain, Israel, the United States, Latin America and Australia have been students of the Chobitko school.

“Once a group of Arabs came to see us wanting to do calligraphy. I told them: ‘I’m sorry, but I don’t know Arabic script.” And they said: “We don’t need you to know it, you just teach us your vyaz lettering. Your vyaz is like our Kufic [Kufic lettering is one of the oldest styles of Arabic script; invented at the end of the eighth century, it played a major role in the development of all Arabic calligraphy - Ed.]”. In the East, the clear geometric forms of characters have a structural underpinning similar to our vyaz,” says Pyotr Chobitko. “Also, there have been many Chinese studying Russian calligraphy among my students. They excelled in vyaz and then mastered uncial and half-uncial [other scripts - Ed.]. They say Russian calligraphy has much in common with Chinese calligraphy.”

In his opinion, vyaz is a kind of passport to the art of calligraphy, in general. It is easy to grasp and, hence, attracts children and adults alike.

“When a person begins to understand vyaz, they discover the full beauty of the Russian language,” says Pyotr Chobitko.

Ornamental vyaz emerged in Byzantium in the mid-11th century, but reached its prime in the Slavic states. The fact is that the letters of the Greek alphabet do not allow for the full exploitation of the potential of the key element of vyaz - the mast ligature (whereby vertical lines of adjacent letters are combined into one). Cyrillic in this respect is indescribably richer since it absorbed the entire Greek alphabet and supplemented it with "authentic" letters to denote sounds specific to Old Church Slavonic. So, for a calligrapher, Cyrillic and vyaz are a “forest” of masts and 400-600 ligatures.

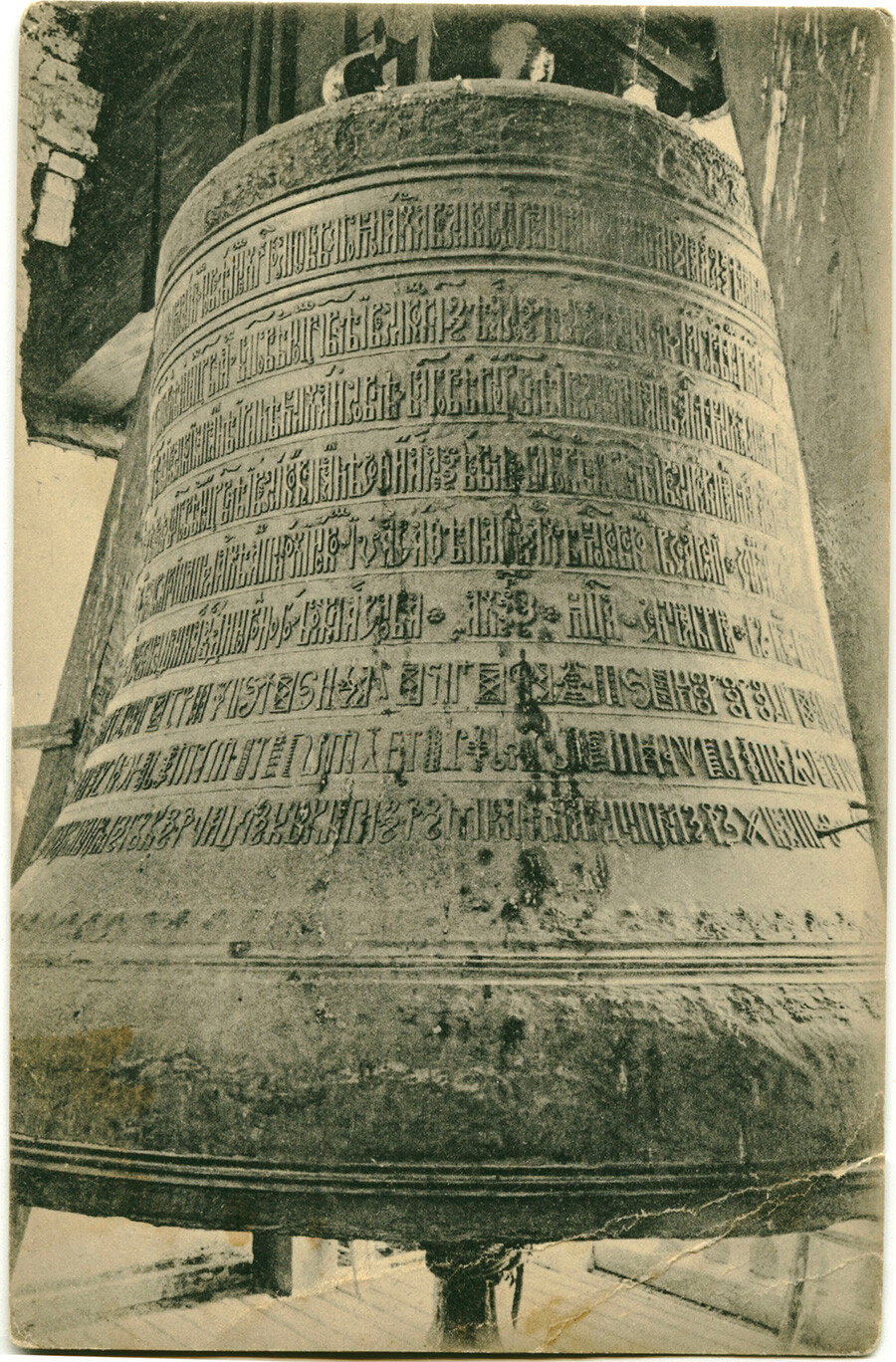

Ivan the Great Bell Tower (Moscow Kremlin).

Alexei Malshev/SputnikAmong the Southern Slavs, the first precisely dated examples of the use of vyaz date from the first half of the 13th century. The oldest is a triumphal inscription of Tsar Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria on a marble column in the Church of the Holy Forty Martyrs in Veliko Tarnovo (Bulgaria, 1230).

A column in Veliko Tarnovo.

Svik (CC BY-SA 3.0)In the 14th century, South Slavic vyaz became richer and more interesting than its Byzantine equivalent. This can first be detected in documents - in the names and titles of Bulgarian tsars and Serbian kings and, later, in all South Slavic manuscripts, notes Russian paleographer Vyacheslav Shchepkin. The fall of these states halted the development of writing techniques, but a Romanian vyaz based on the South Slavic version emerged in the 15th century. This “transfer” of writing style evidently took place via the ‘Holy Mountain’ monastic center on Mount Athos.

Zvenigorod Bell of Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery.

Public DomainIn Rus’, vyaz emerged in the late 14th century and, in the 15th, it became widespread in Novgorod, Pskov, Tver, Moscow and also at the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius, the center of the Russian written language. By the end of the 15th century, it had become the most widely used writing style in Russia.

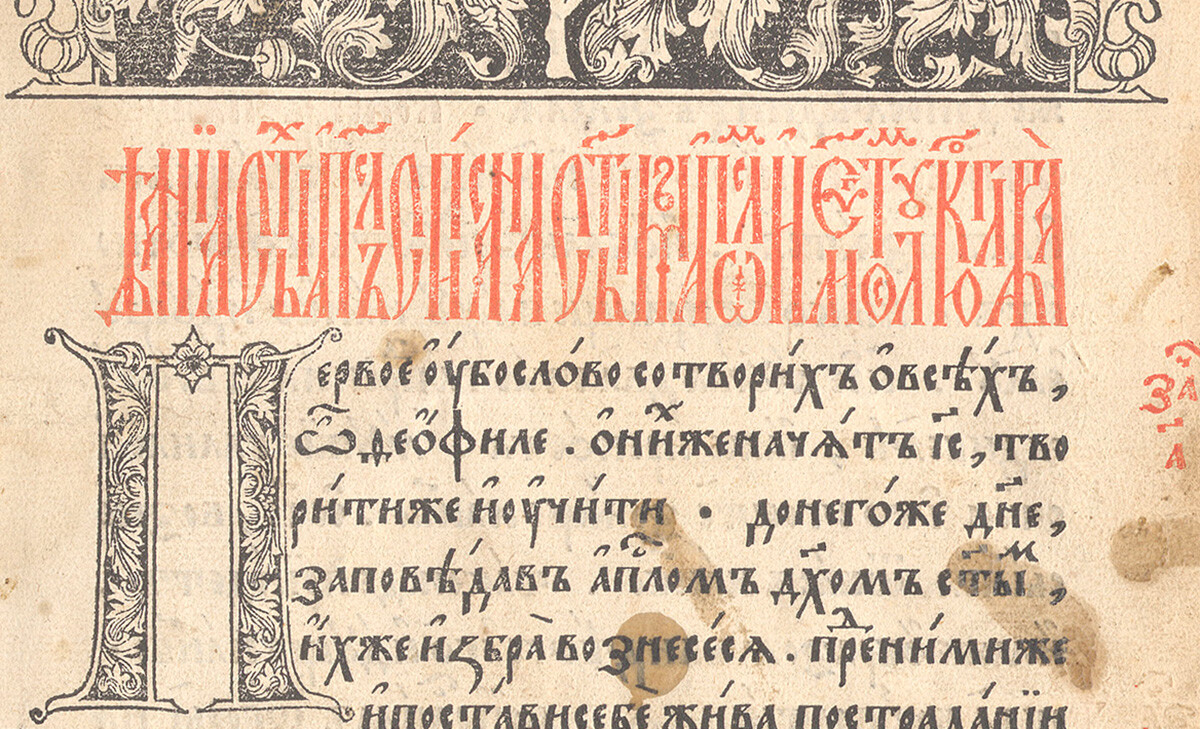

The Apostle is the first dated printed book in Russia.

Public DomainIn the years 1708-11, however, Peter I carried out a reform of the Russian alphabet and introduced a secular script close in appearance to the Western style. So, from that time vyaz survived predominantly among Old Believers opposed to state-imposed innovations.

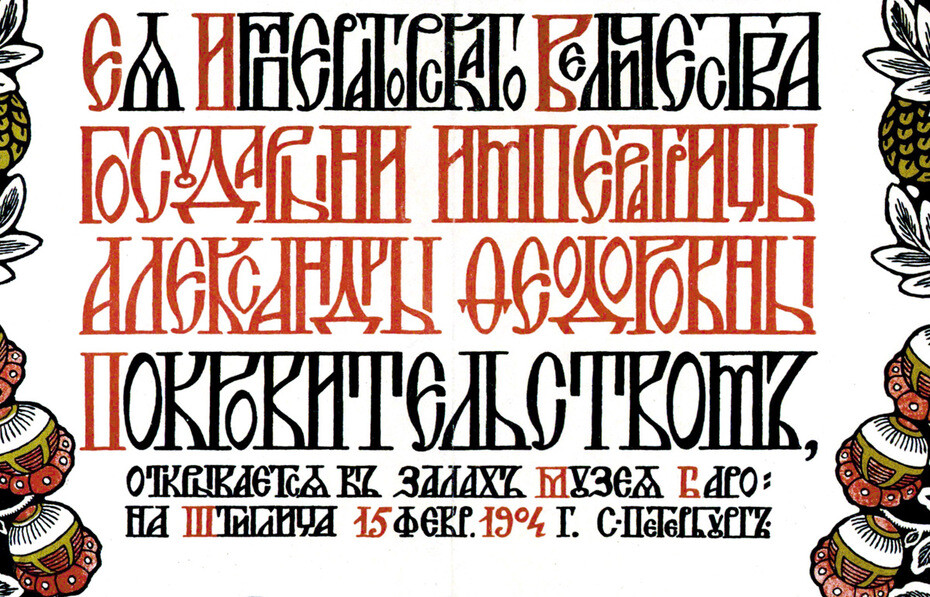

I. Bilibin. Poster "Historical Exhibition of Art Objects for the Wounded and Hungry," 1904 (fragment).

Public DomainRight up to the end of the 19th century, vyaz was used for the design of church books, icons and church interiors. The ‘Mir iskusstva’ (‘World of Art’) movement (1898-1927) brought about a revolution in its use after its artists set out to rediscover the artistic value of ancient lettering.

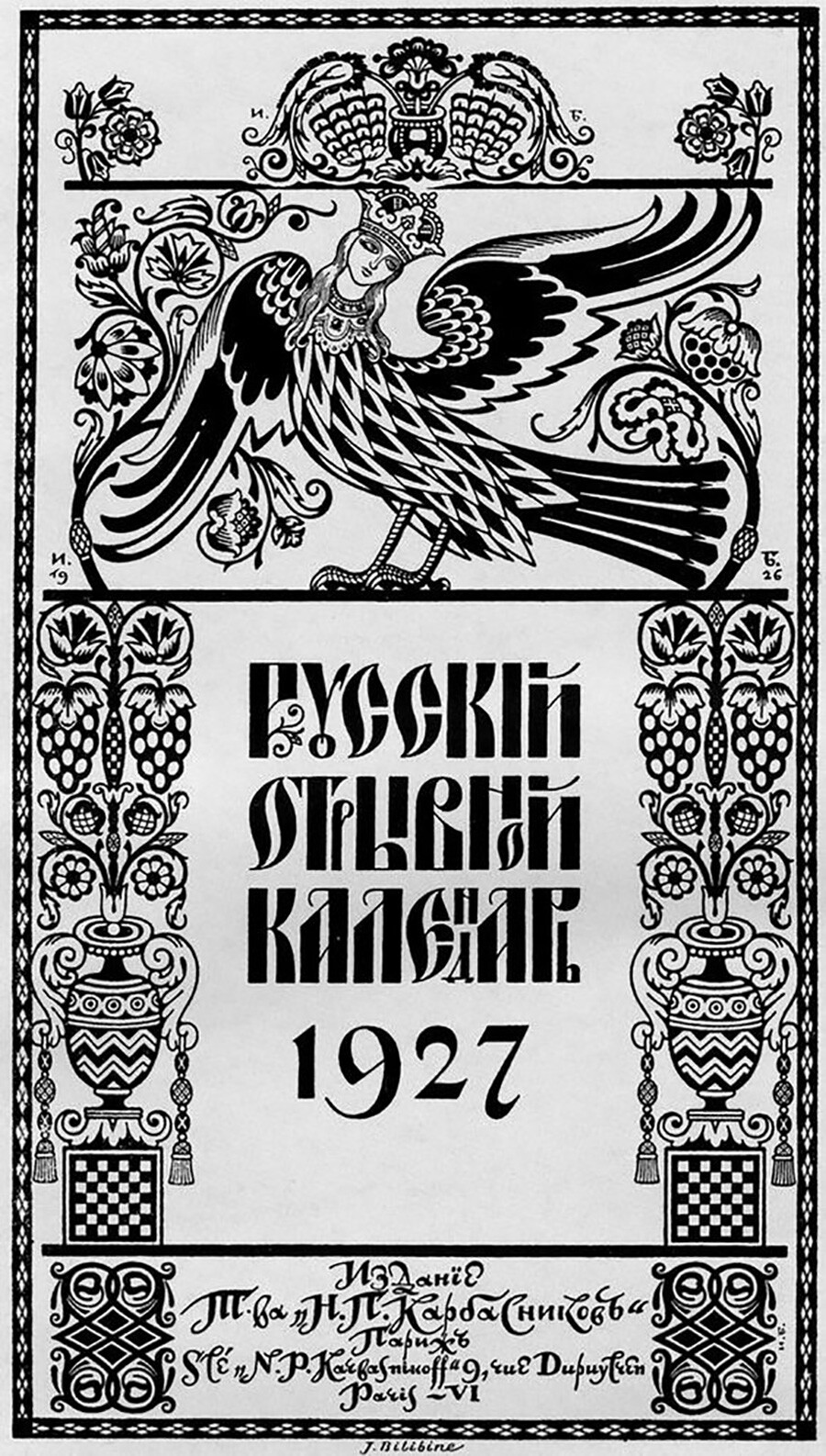

Russian calendar for 1927, I. Bilibin.

Public Domain“[Russian artist and book illustrator] Ivan Bilibin started to use vyaz in the design of books, advertisements and posters. Interesting artistic effects based on combining vyaz with elements of the Art Nouveau style were achieved by the artist Mikhail Vrubel. Simultaneously, the principal artist of Russian folklore, Viktor Vasnetsov, used vyaz in the decoration of cathedrals and even the design of stamps,” writes Pyotr Chobitko.

Stamp of voluntary fundraising for victims of the World War I.

Public DomainHe notes that vyaz finally escaped the narrow confines of church use at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries and acquired wider applications: It found its way into typography and started to be used in book design and in the decorative and applied arts.

Pyotr Chobitko and his pupils have contributed to the revival of calligraphy in Russia in the 21st century. They played a part in organizing the first international calligraphy exhibition in St. Petersburg in 2008. At subsequent exhibitions in Moscow, Novgorod, St. Petersburg and Tallinn particular prominence was given to Russian scripts and, in particular, vyaz and it, thus, gained in popularity again. Its decorative and ornamental qualities, as well as its particular rhythm and structure, have inspired designers and vyaz has started appearing everywhere, from packaging and jewelry to the interior design of private homes and public spaces.

At the same time, street and graffiti artists, having exhausted their stock of Western motifs, have also started using vyaz in their work.

Some of them, such as Pokras Lampas, are trying to combine Western Gothic with Russian vyaz: Both types of lettering involve the use of a broad flat brush. Vyaz today, thus, provides original material for experiments in calligraphy.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox