Mercenaries in Russia: How Westerners shaped the army

The first Russian fleet. Miniature from the Russian manuscript of the XVI century. The Illuminated Chronicles of Ivan the Terrible (Litsevoi svod). State Historical Museum, Moscow.

Global Look PressMercenaries had long had a place in the Russian army, but beginning in the late 15th century, they started to play an even more significant role. The style of warfare had become much more sophisticated over the years, and Russia needed skillful military specialists from countries that already adopted advanced military techniques. As a result, the Russians began to recruit these types of fighters from the West.

The inflow of Westerners into the Russian military service began at a time when the Moscow principality was evolving into a centralized Russian state (in the second half of the 15th century during the reign of

“Aristotele ” and the production of cannons in Russia

The man sometimes referred to as the first Western mercenary in Russia was the Italian engineer and architect Ridolfo “

"Cannons' court on the Neglinka River" by Apollinary Vasnetsov.

A. Sverdlov./RIA NovostiFioravanti took part in a number of Ivan III’s military campaigns as the head of the artillery. Some people think that it was due to the role of “Aristotele,” and other Italian military engineers, that artillery in the Moscow state was the best in Eastern Europe at the time.

When Ivan III’s grandson, Ivan IV (or Ivan the Terrible) took the throne in the middle of the 16th century, Russia experienced a strong influx of foreign military experts. The tsar not only brutally suppressed any real, or even potential, opposition to his rule, but he also pursued active foreign campaigns both eastward and westward. In order to do it, he introduced the first regular units in the army: Streltsy regiments. During the constant wars of his reign, Ivan IV relied heavily on Western military specialists. By the end of his rule, in 1584, European mercenaries accounted for around 4,000 to 5,000 soldiers out of the 100,000 men serving in the Russian army.

"Blessed Be the Host of the Heavenly Tsar". Russian icon, ca. 1550 - 1560. The icon is traditionally perceived as an allegorical representation of the siege of Kazan by the troops of Ivan IV.

The State Tretyakov Gallery.The first Russian fleet

Ivan the Terrible was the first Russian monarch who, as a result of his battles with Poland and Sweden, attempted to shift the fighting into open water and founded the first Russian fleet in the Baltic Sea. He put this fleet under the command of a foreigner, a Danish admiral, and headquartered it at the newly captured port of Narva. In 1570, Ivan the Terrible’s fleet consisted of six ships manned by crews of primarily Danish and German mercenaries.

Ivan IV's fleet was quite successful in battling Polish and Swedish ships.

Global Look PressThe fleet was quite successful as it battled Polish and Swedish ships. However, Denmark soon seized the fleet, possibly because of their fear of Russia’s strengthening position in the Baltics.

Outlandish styles of war

The reign of Ivan IV was only the beginning of the increase in the number of foreign mercenaries fighting for Russia. The first two czars of the new Romanov dynasty, who ruled in the 17th century, continued the policy of inviting Western military pros, which was complemented with deep reforms of the Russian army. The first Romanovs, Mikhail I, and his son Alexis I closely watched the events of the Thirty Years’ War in Europe and decided to try importing whole structures from contemporary Western military organizations. In Russia, Regiments of the New (Outlandish) Style came into being.

The army of Mikhail I. "Entry of Tsar Mikhail Feodorovich in Moscow on May 2, 1614" from the reserves of the State Historical Museum in Moscow.

RIA NovostiThese included permanent, established army units, as opposed to the prior practice of assembling the nobility’s voluntary army, only in the case of war, and relying upon not that numerous Streltsy regiments. Outlandish Regiments were created in both the infantry and cavalry. In most instances, these units were led by foreigners with many other non-Russians among their ranks.

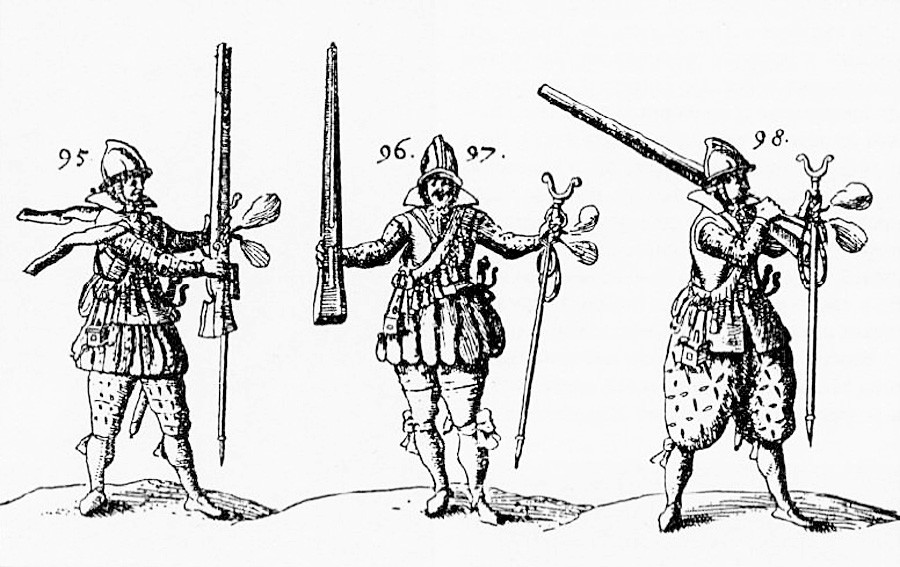

The fighters of the Regiments of the New Style.

Public Domain.By the middle of the 17th century, half of the cavalry regiments had foreign-born mercenaries as commanders. In the infantry, the presence of mercenaries was even more obvious—they headed all eight regiments. These units proved to be efficient and, slowly, the bulk of the army followed suit.

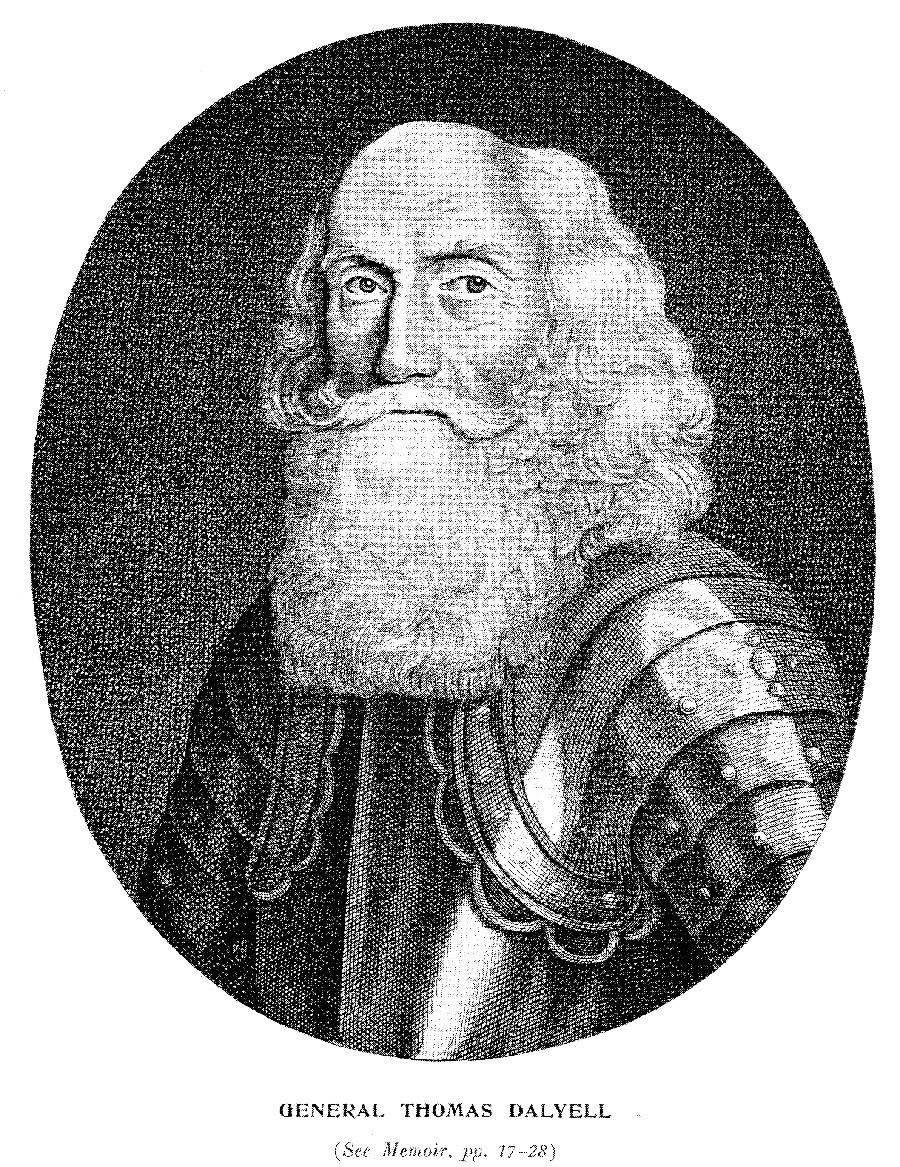

The Scots in the Russian army

Among the mercenaries of the time was George Learmonth from Scotland. He was a cavalry officer and after coming to Russia he adopted the name Yury Andreevich Lermontov. He would go on to found the family whose most famous member is the 19th-century poet Mikhail Lermontov. The person who was in charge of training the Russian soldiers for new regiments in the 1650s was another Scot, the general Thomas Dalyell who had been an active participant in the British Civil Wars.

Engraving of General Thomas Dalyell from "The Scots Army 1661-1688", by Charles Dalton. Published in Edinburgh by William Brown, 1909.

Public DomainMany of these mercenaries remained in Russia even after their services ended. In fact, 2 of the 7 “foreign” generals serving at the beginning of Peter the Great’s military campaigns (in the early 18th century) were descendants of mercenaries that had emigrated to Russia. As historian Vyacheslav Tikhonov pointed out, from the early 17th century, whole dynasties of foreign members of the military made their homes in Russia. For generations, they served in the Russian army, and, eventually, they would be considered “local” foreigners.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox