Creativity behind bars: 3 great innovations made in Stalin’s prisons

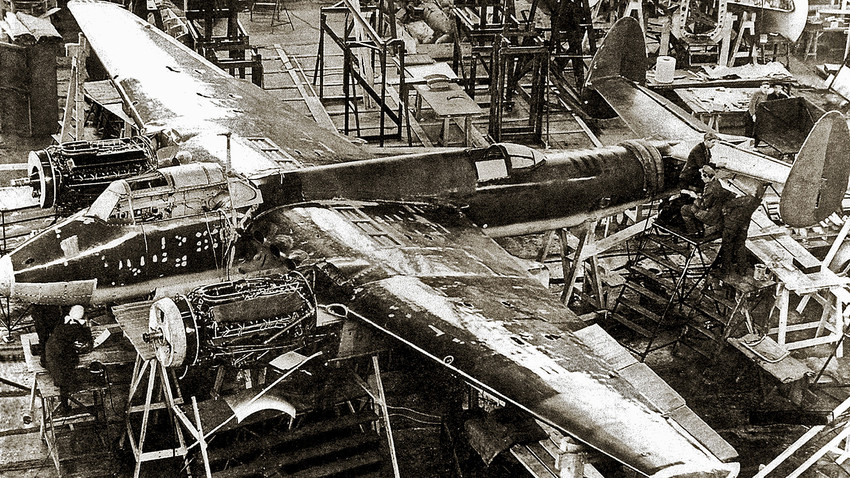

Assembling of a developmental prototype of Tu-2 "Bat" bomber

Wikipedia‘The Thing’

In August 1945, U.S. Ambassador W. Averell Harriman received a present from the USSR’s Young Pioneers organization. The delegation of Soviet children - amid the end of war, celebratory atmosphere and continuing cooperation between the two nations - gave him a carved wooden plaque of the Great Seal of the United States. Harriman put it on his study wall. He and three of his successors were fond of the gift, which adorned the same spot on the wall for seven years. Little did they know it concealed a secret.

A replica of a bugged US Great Seal on display at the National Cryptologic Museum

Austin Mills / Wikipedia

In 1952 it was revealed that the plaque contained “The Thing,” one of the first covert listening devices. It was designed using advanced technology: It had no power supply or active electronic components, and was activated only when it received a radio signal of a certain frequency. It was extremely hard to detect and was discovered only by accident.

The Thing gave the Americans the jitters as Washington didn’t possess such technology. It was designed by famous Soviet inventor Lev Termen (or Leon Theremin as he was called in the U.S.). He is best known for creating the first electronic musical instruments: The theremin (aka. termenvox).

Theremin lived in America in the 1930s, popularizing his termenvox and working on burglar alarm systems. In 1938 he was recalled back to the USSR where he was arrested a year later and accused of planning the murder of high ranking Soviet official Sergei Kirov, who was killed in 1934 when Theremin was in the U.S. The prosecution claimed the conspirators planted a radio-controlled bomb in an observatory in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) and that the inventor was supposed to detonate it from across the Atlantic - however, Kirov was in fact shot dead by the husband of one of his employees.

After his arrest he worked in a “sharashka” prison developing espionage devices, one of which was “The Thing”. He was awarded the State Stalin Prize in 1947 when he was released from prison.

Dive “Bat” bomber

Theremin spent his jail term in the TsKB-29 design center. It was under the auspices of the Internal Affairs Ministry and the most of its staff were prisoners. Among them was pioneering aircraft designer Andrei Tupolev. In fact, the “sharashka” itself was named after him - Tupolevka - as its main objective was to develop new military planes.

Tupolev was thrown into the slammer in 1937 for alleged sabotage and espionage. He later told a friend that he was not beaten but instead deprived of sleep. Hence, he “confessed” that for more than a decade he had been a French spy. In 1940 he was sentenced to 15 years in a prison camp but was released the following year, when the Great Patriotic War started.

During the years in prison he developed the Tupolev Tu-2 bomber (“Bat” as it was later referred to in NATO classification), which became a major bomber of WWII with its excellent overall design. The face it was designed behind bars makes its success especially remarkable. It was one of the main Soviet medium dive bombers in WWII.

The bomber was manufactured for 10 years until 1952. Around 2,500 Tu-2 aircrafts were made. It also took part in the Korean War and the plane was widely used by countries that would later sign the Warsaw Pact. Tupolev received the State Stalin Prize in 1943. Three more Stalin Prizes followed for his other developments.

Anti-pellagra medicine

It wasn’t only espionage pros and aircraft designers who were locked up in special prisons during the purges. Famous Soviet virologist Lev Zilber spent four years in a “sharashka”. He was arrested on the basis of a colleague’s denunciation report and accused of plotting to poison Moscow’s water supply system, landing him a 10-year sentence.

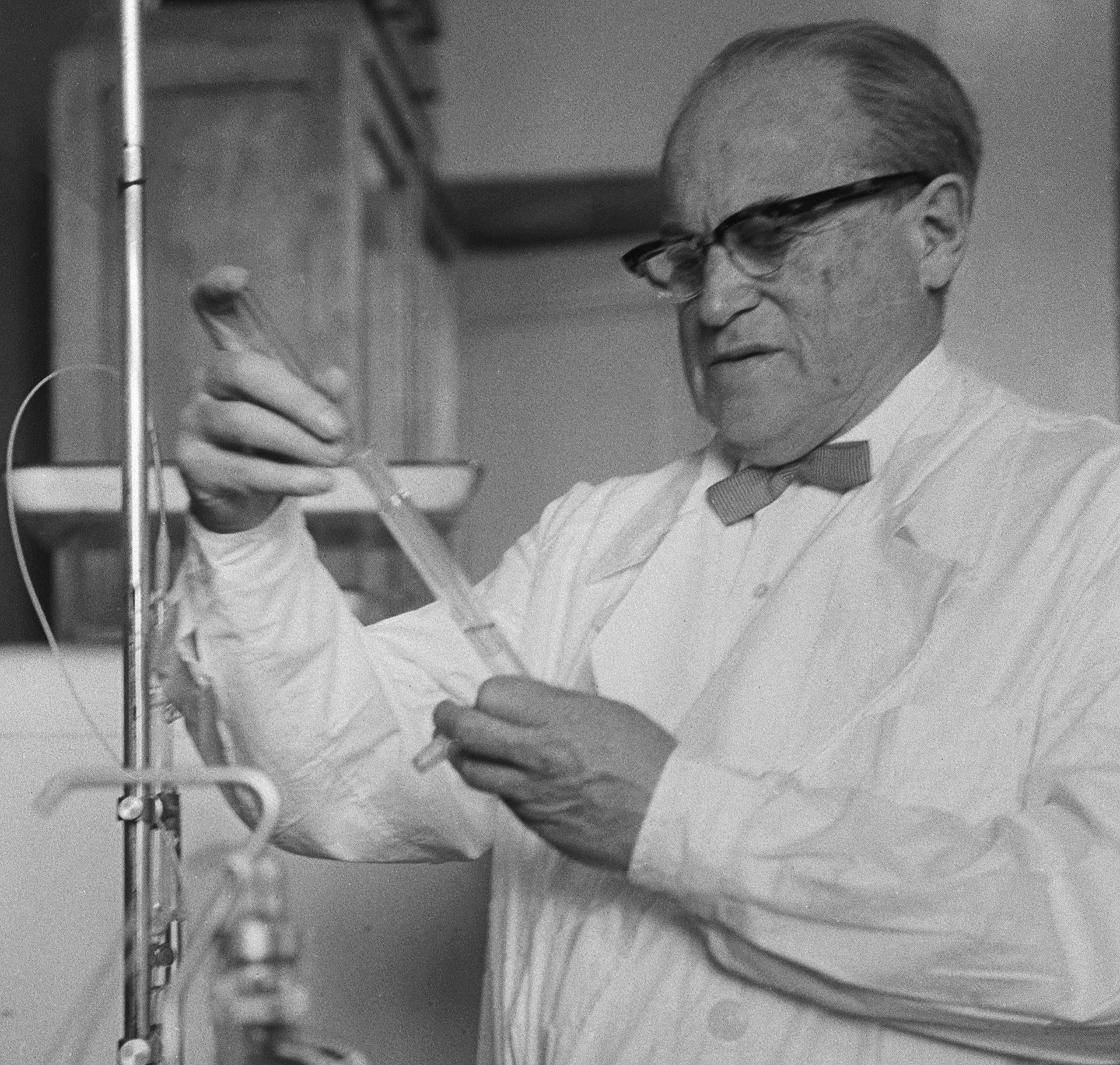

Lev Zilber working in a laboratory of the Scientific Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology

Oleg Kuzmin/TASSFirst, he worked cutting trees before landing a gig as a camp doctor. While in the prison hospital he encountered pellagra, a serious disease caused by a deficiency of vitamin B3 and characterized by dermatitis and dementia. If left untreated treated it usually results in death.

The camp was in Russia’s northern region so the scientist used reindeer lichen to produce yeast that became a source of vitamins, he recalled later. This formed the base of his medicine, Antipellagrin, which proved effective for those suffering from the disease, so he patented it, although instead of his name, the Ministry of Internal Affairs mentioned in the document.

Zilber was eventually moved to a closed laboratory where he worked on his theory about “cancer’s viral nature.” Two years after his release in 1946, he also received the State Stalin Prize for his book about encephalitis.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox