An American merchant sailor remembers the Arctic convoys during World War II

SS 'Cornelius Harnett,' Newport News, Va., June 1945

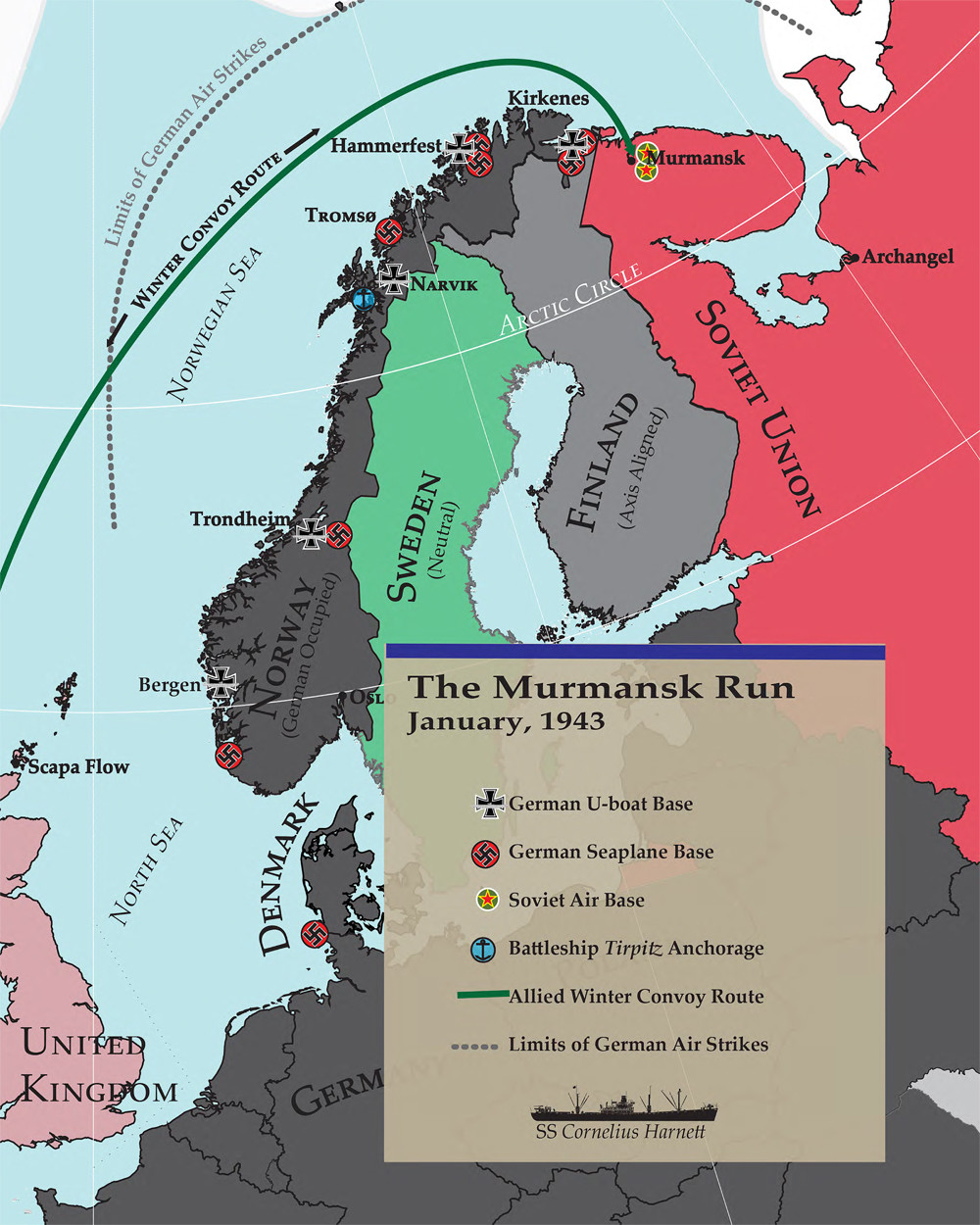

Library of VirginiaBritish Prime Minister Winston Churchill called it “the worst journey in the world.” Sailors on nearly 80 convoys from August 1941 to May 1945 risked their lives to help the Soviet people. Herman E. Melton, an American participant in these events that took many lives in the frozen Arctic, published his recollections of that harrowing time in the book, Liberty's War: An Engineer's Memoir of the Merchant Marine, 1942-1945.

Melton recalls how he was sent as a cadet from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy to serve on the Liberty ship, Cornelius Harnett. He describes the crew’s everyday life, the days spent in the port city of Murmansk and reveals some lesser-known facts about the convoys.

Herman Melton, July 1943.

H. Edgar Melton, Jr.***

Anderson [chief engineer] also helped me to understand the stakes of our voyage. At this point in the war, the USSR had its back to the wall. Both Leningrad and Stalingrad were under siege by the advancing German army. The supply route to Murmansk was absolutely vital to Russian survival. Without Allied ships laden with products from the American industrial arsenal, the USSR might not succeed in beating back the German invasion of Russia. Josef Stalin was demanding help, and Roosevelt pressed Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill to protect the American merchant ships and keep the Soviet Union in the war. So desperate was the situation that, in the summer of 1942 Churchill wrote to the Admiralty that the next convoy “is justified if half [the ships] gets through. Failure on our part to make the attempt would weaken our influence with both our major allies.”

Convoy RA-53 departs Kola Inlet, March 1, 1943

Imperial War Museum, LondonDuring the course of the war, merchant ships carrying everything from shoes to fighter aircraft sailed on this most hazardous of all voyages for merchant seamen in World War II. Of the 800 ships that made the Murmansk Run, 97 failed to reach their destination and return. Storms, ice, mines, collisions, fires, U-boats, and the Luftwaffe took their toll. Some 3,000 Allied seamen lost their lives in the north Russian convoys.

There are excellent records from the war that show the enormity of our support of the USSR via the Murmansk Run. Ships of the north Russian convoys carried more than 3.9 million tons of material from Allied nations to the Soviet Union. Of all American aid to the Soviets, nearly one-quarter was funneled through the narrow lanes of the Arctic convoys. Before the war was over, American shipments to the Soviet Union would total 14,795 aircraft; 7,537 tanks; 471,257 trucks, jeeps, tractors, and motorcycles; 11,155 rail cars; and 1,981 locomotives. The [SS Cornelius] Harnett carried a steam locomotive in its cargo, for use in transferring the war materiel carried by the convoys from Murmansk to the front. The need for a steam locomotive was so critical that two other ships in the convoy (one being the Nicholas Gilman) also carried locomotives, in the hope that at least one of them would arrive safely.

Convoys to north Russia also carried more than 345,000 tons of ammunition and TNT, and on the

As the dangers loomed ever larger and more real, my studies became a refuge from fear, helping, for a few moments, to rid my mind of the risks I faced. There were quiet moments, too. Despite the bone-chilling wintry cold, my watch duty on deck was often a time of spectacular light shows by the aurora borealis, the northern lights that flashed every color of the spectrum. Other fireworks were not long in coming for the Harnett.

<…>

On my last visit ashore in Murmansk on 27 February, I witnessed a [German dive bomber] Stuka’s deadly attack on [merchant ship] El Oriente. I was alone and had to pass through numerous gates to leave the docks. At each stood a woman sentry with a rifle and its needle-pointed bayonet, and the only English each seemed to know was the stern demand “Your pass, comrade!” After clearing the last gate and entering the town’s streets, I reached a hill high above the harbor. Looking down on the docks below, I heard the frightening whine of a Stuka dive bomber screaming down toward the pier to my left. The Stuka pulled out of its dive just as its bomb struck the stern deckhouse of the El Oriente, putting it out of commission and killing four men of the armed guard crew. I shivered because El Oriente was standing at the same dock as the Harnett. Somehow, the El Oriente was patched up in time to join our convoy, which departed three days later.

German Stukas attack convoy at Murmansk docks

Painting by Jim RaeJames Harcus of the [British merchant ship] Ocean Faith also mentioned the dive bombing of the El Oriente in his diary, referring to the ship as “the Lorentis.”

Sat 27th

We have had a lovely clear day today & were settling down for a quiet afternoon when we heard a plane diving. He dropped a bomb not far from us on the starboard side & another on a ship at the wharf we left on Thursday. Some of the lads told us it was the ship that took our place, a Panamanian the Lorentis & she was lying the opposite way round from us & was hit on the stern right in the gun pit, a few number not known were killed.

Later, as the Ocean Faith moved to another wharf, Harcus noted that another ship, the Empire Portia, was being towed up the river with its No. 2 hold on fire, another Stuka victim. He also described how four German aircraft attacked Murmansk, dropping mines in the river and closing the port for shipping until minesweepers could clear the channel.

Ruins of Murmansk after the Second World War

Yevgeny Khaldey/TASSFemale laborers were everywhere in Murmansk and they made up most of the stevedore crews unloading the supply ships. Their shifts were twenty-four hours on and twenty-four hours off. There was no fraternizing whatsoever, and the women responded not at all to friendly overtures. Neither did the few Russian men we encountered. Any men we saw would have been classified 4-F by an American draft board. All able-bodied men were at the battlefront.

I believe that many of the Russian workers were political prisoners, forced into slave labor and starving. One story I later heard about the unloading of the Harnett’s cargo involved a stevedore caught eating from a tin of canned meat that had broken open when a cargo sling failed. As the hungry worker helped himself to the spilled contents, a guard took him behind a stack of cargo and shot him on the spot. Such stories contributed immensely to the depressing atmosphere that enveloped Murmansk.

Medal ceremony, Embassy of the Russian Federation, Washington, D.C., Dec. 8, 1992

Author's CollectionText copyright © 2017 Will Melton

Read more about the Arctic Convoys: Through ice and fear for Russia.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox