The forgotten story of how the Baltic states brought down the Soviet Union

On August 23, 1989, several million residents of the Soviet Baltic republics – Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania – staged the largest peaceful protest ever in the USSR. Joining hands, they formed a human chain that linked the three Baltic capitals – Riga, Tallinn and Vilnius. Stretching over 600 km, the human chain entered the Guinness Book of Records as the longest in history.

The protest was prompted by the disclosure of new details concerning the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a sensitive issue for all of Eastern Europe.

For nearly half a century, the Soviet Union denied the existence of secret protocols that led to the division of Poland and the annexation of the Baltic states. However, with the advent of Perestroika, the taboo on the research and discussion of these topics was lifted. On August 18, 1989, the USSR admitted the existence of a secret protocol to the Soviet-German pact.

The Soviet officials said that the pact had no effect on the three Baltic states joining the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, a chain reaction had already started in those republics. On August 22, the Supreme Soviet of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic accused the USSR of a forcible occupation of the Baltic states, and on the following day, the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, millions of people joined a protest that came to be known as the Baltic Way.

Participants were convinced that since the inclusion of the Baltic states into the Soviet Union in 1940 took place through force, then the current Soviet government, its laws and constitution were unlawful on the territory of the Baltic states. Thus, they believed that Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia should automatically restore their sovereignty within the pre-1940 borders.

In a great hurry, just a couple of days before the demonstration, organizers meticulously planned the route and the approximate number of participants, taking into account the terrain. The biggest problem was transportation: they needed a large number of buses to take protesters to remote and sparsely-populated places on the human chain route, and then to bring them home.

People brought flowers and mourning ribbons to commemorate victims of Soviet repression, and they hung the Baltic states' pre-war national flags, as well as put on folk costumes and sang folk songs.

The Baltic Way demonstration brought together some 2 million people, or about a quarter of the population of the Baltic republics at the time.

The Kremlin didn't approve of the protest, describing it as a manifestation of nationalism, but they did not try to stop it. The event received extensive coverage in local media, and participants were given time off work. Public buses were taken of their regular routes to transport the protesters. The police didn't interfere, and even tried to control traffic and ensure law and order. Nevertheless, the roads were gridlocked with thousands of cars as people wanted to join the human chain.

The Baltic Way culminated at seven in the evening, when people along the human chain joined hands for 15 minutes. Those who did not make it to the main event formed hundreds of small solidarity chains.

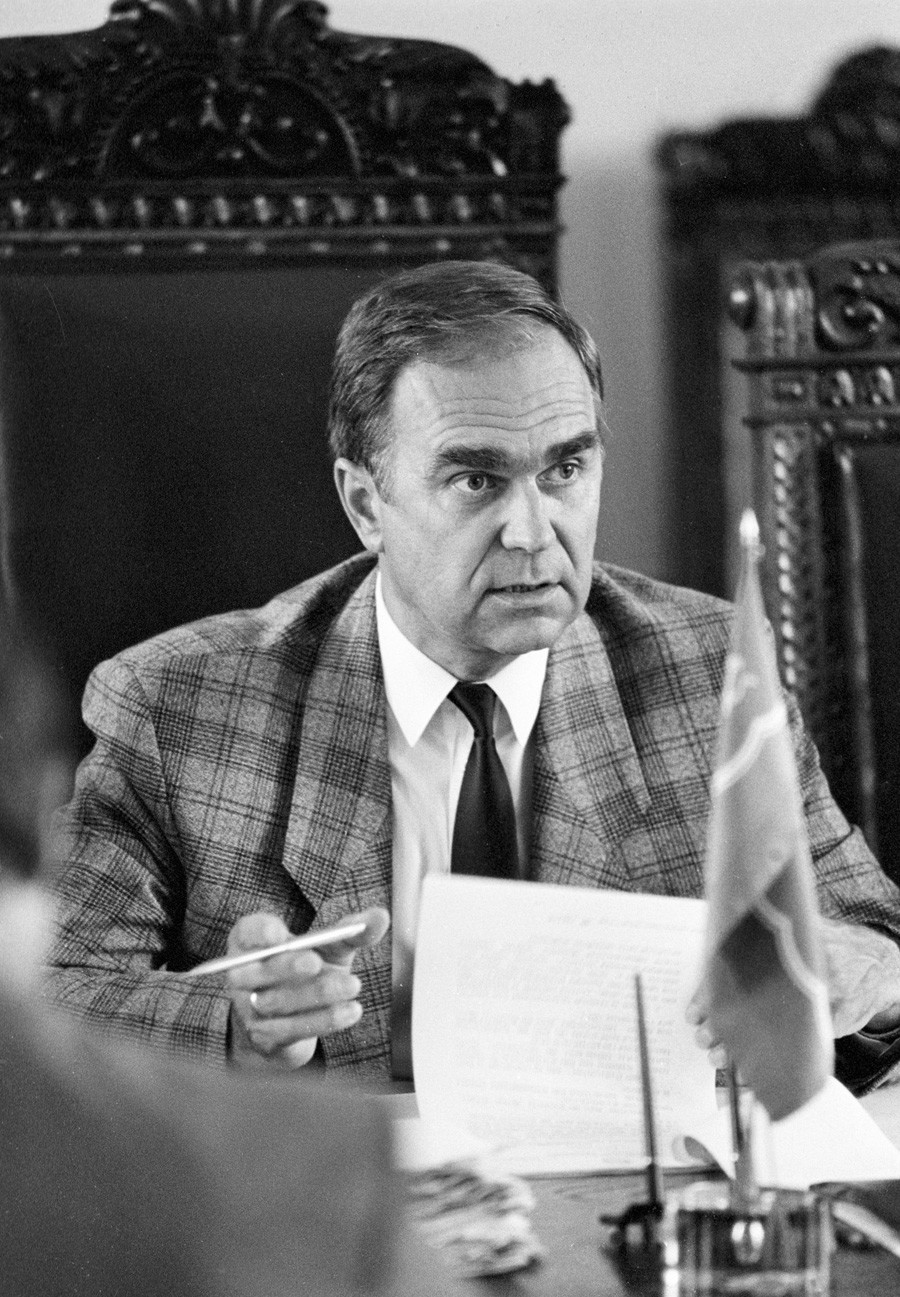

As chairman of the Estonian Council of Ministers, Indrek Toome said on this day: "People present here want to feel that they are united and that they stand for something very big."

"The word ‘independence’ turned everybody's heads. People lived in the USSR and wanted something new; everybody thought that things would be different. Yet few people thought of what independence would lead to in practice," recalls Galina Greydene.

It was not only ethnic Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians who took part in the demonstration. There were also many Russians. "I was little and did not fully understand what was happening; but through my mother and grandfather I felt that it was something important and necessary," says Maxim Kushnarev.

"It was very beautiful, very symbolic and very emotional. It was a big sign both for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the West that people of the Baltic republics were united in their movement, in their desire to restore independence. It was a very beautiful gesture," recalls a participant in those events, former Latvian Foreign Minister Jānis Jurkāns.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox