Today considered an expensive delicacy, beluga or sturgeon caviar—freshly salted or pressed, served with champagne or vodka—was quite affordable in Soviet times and even saved a few lives.

1. Caviar was used as a currency

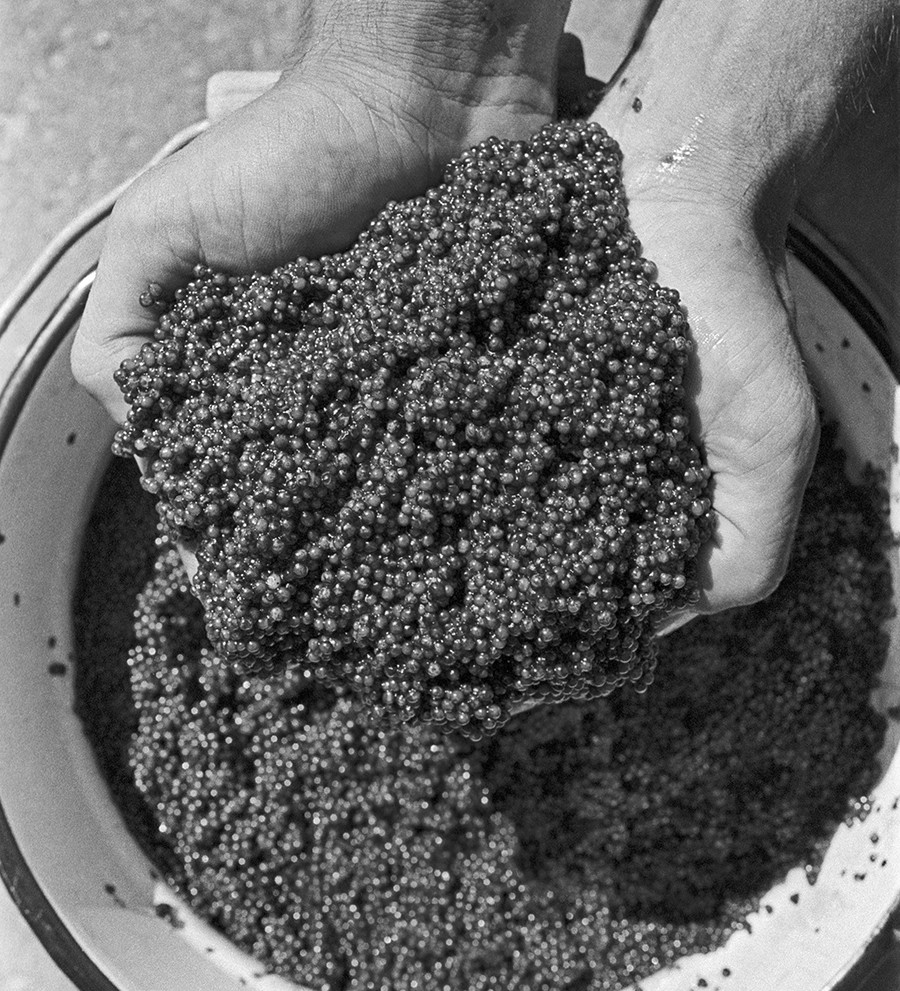

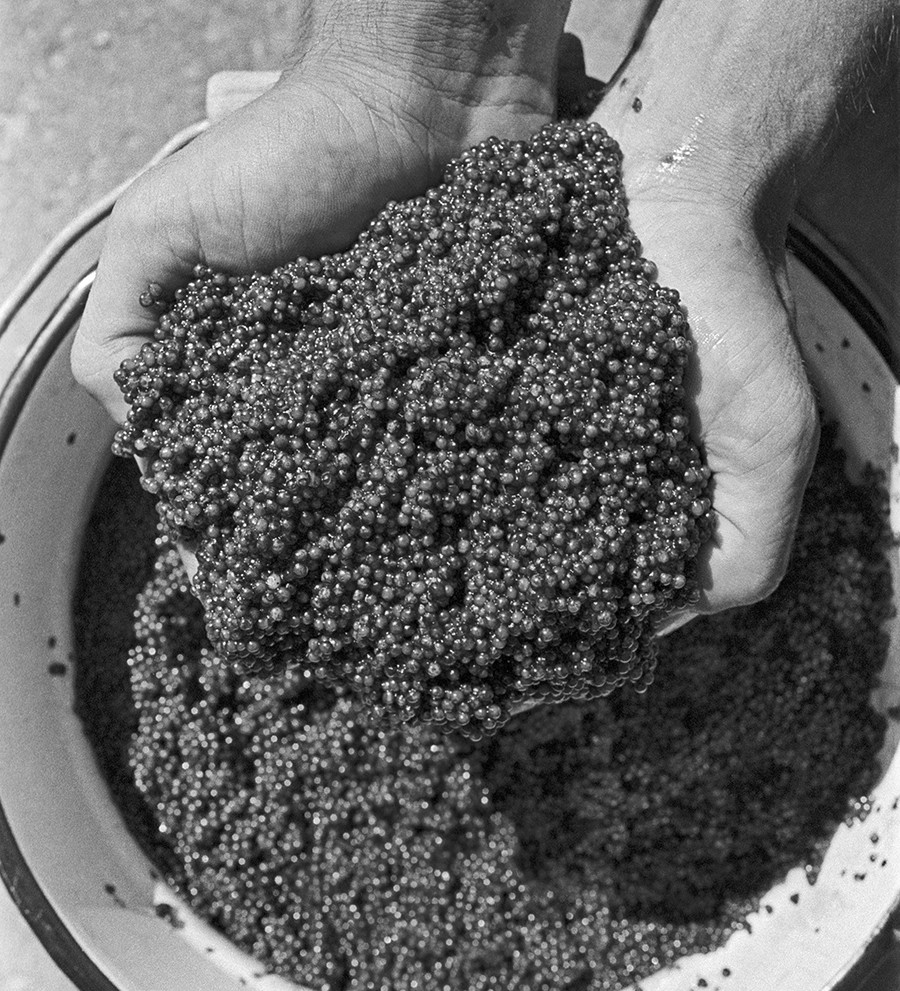

Products of the Caspian caviar- balyk production association

V. Kalinin/Sputnik

During World War I and the Russian Civil War, sturgeon fishing was not a priority industry, causing it to decline sharply and fish numbers to swell. As a consequence, the post-war years saw a boom in the caviar industry—the late 1920s and 1930s were rolling in the stuff and it was pretty inexpensive.

The export of this other "black gold" was one of the factors that enabled the Soviet Union to industrialize at an unprecedented pace.

Black caviar seized from poachers

Eduard Kotlyakov/TASS

Caviar was the country’s tenth most exported product, after timber, oil, fur, etc. According to Pavel Syutkin, author of True Stories of Soviet Cuisine, in 1929 the USSR exported almost 800 tons of black caviar, for which it received $15 million (almost a billion dollars at today’s exchange rate).

2. Caviar was washed down with vodka

Thanks to Dyagilev and his touring Ballets Russes, in Europe all things Russian were in vogue, including black caviar. Refined Europeans sipped champagne with chilled grains of roe. Incidentally, back in Russia, caviar was served more often at room temperature (it was frozen only for export).

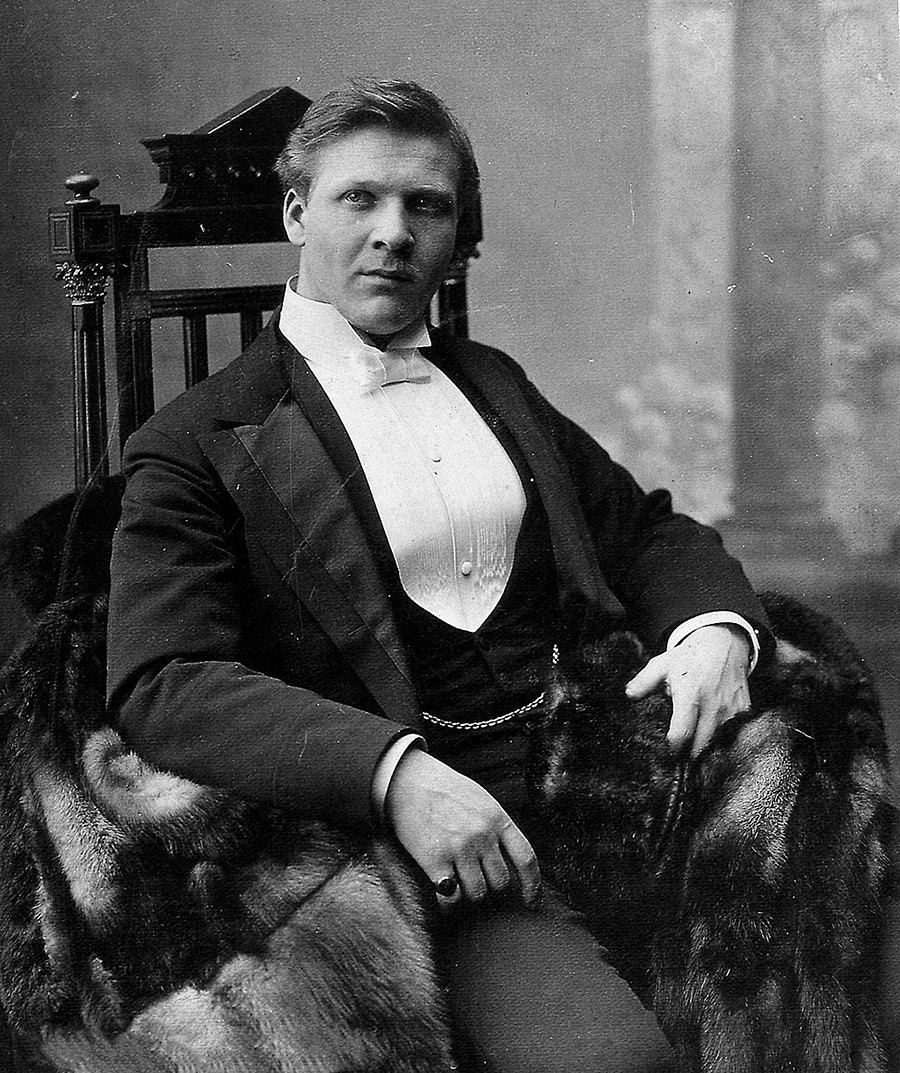

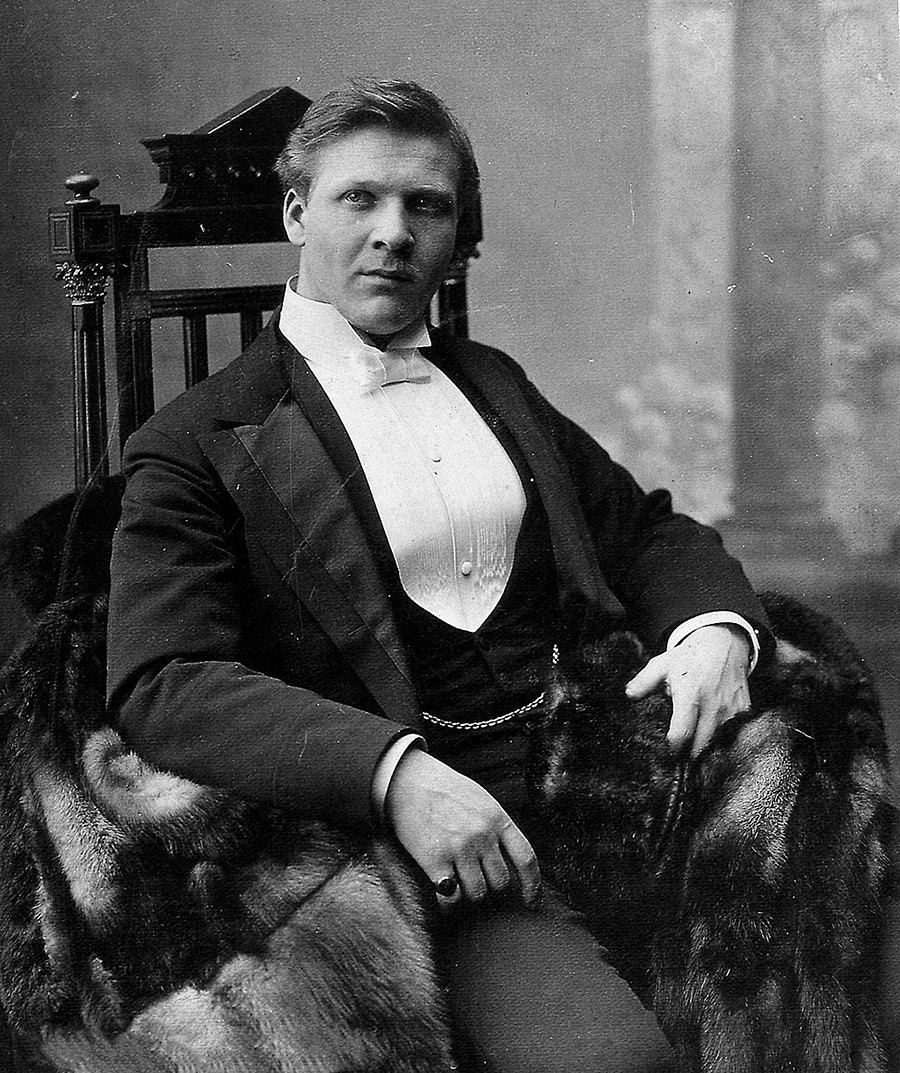

Feodor Chaliapin

Maxim Dmitriev/Wikipedia

Opera singer Feodor Chaliapin is credited with the phrase: “Caviar is not a "zakuska" (snack) after a vodka shot, it is meant to be washed down with vodka.” Besides his sonorous bass voice, the extravagant artiste was renowned for his sumptuous feasts at the finest restaurants. A true gourmet, he was especially fond of black caviar. According to the memoirs of a contemporary, artist Konstantin Korovin, during a tour of the Volga region Chaliapin ate caviar not at restaurants, but at riverside fish stalls, where he asked for the sturgeon to be sliced open in front of his very eyes.

3. Caviar saved lives during the war

Packing black caviar for export

Getty Images

In the early days of the Nazi blockade of Leningrad, frightened residents desperately tried to stock up on foodstuffs, buying anything available (ration cards were soon introduced and the free sale of food ceased). Huge lines of people formed everywhere.

Hermitage Museum employee Tamara Korshunova, who lived through the siege as a little girl, says that before the introduction of cards, the fish shop opposite her home still stocked black caviar. It was not snapped up simply because it was too expensive and ordinary people didn’t know what it was. “We bought a big jar, which basically saved our lives,” she recalls.

Canning black caviar of sturgeon caught in the Volga River

Valeriy Shustov/Sputnik

Being especially rich in vital vitamins and trace elements, black caviar was added to the rations of military pilots and submariners.

4. Caviar cured children

In the 1970s and 80s, pediatricians advised feeding caviar to children suffering from low levels of hemoglobin and iron. Anxious mothers rushed to pour caviar down their children’s throats, often inducing a lifelong aversion to the delicacy, and even allergies. Incidentally, the question “What are the best black caviar substitutes?” sometimes appears on today’s online forums for young mothers. Some old-school doctors still recommend it to help combat anemia.

Caspian caviar-balyk production association. Caviar packing in caviar shop floor

Ivan Zakharchenko/Sputnik

Caviar is not a medicine, of course, but nutritionists believe that the proteins it contains are good for the cardiovascular system, brain activity and vision, and generally raise immunity. Black caviar is more wholesome than red, but eating it every day is not advised due to the risk of developing kidney stones.

5. Caviar has been the subject of satire

In restaurant of Ukraina Hotel

TASS

After the death of Stalin, the price of black caviar shot up and it ceased to be an affordable delicacy. Henceforth, only the elite could enjoy it. The red variety was a bit cheaper, but still off-limits to most. People often saved up and purchased it only at New Year.

Instead of black and red caviar, there appeared various tinned vegetable snacks made from marrow and eggplant, which in the USSR were also branded as caviar. It was cheap and plentiful, but unpopular with shoppers (even during terrible shortages, lonely tins were left sitting on shelves).

The changing face of caviar over the years didn’t escape the attention of satirists. In the popular comedy Ivan Vasilievich: Back to the Future by famous Russian director Leonid Gaidai, there is a scene that shows a royal feast from the time of Ivan the Terrible. Among the cornucopia of dishes on the table are three silver caviar bowls: the first contains a huge amount of black, the second slightly less red, and the third no more than a teaspoon of “foreign eggplant” caviar. But it is this third sort that the 16th-century master of ceremonies salivates over, ignoring the black and red.

A screenshot from 'White Sun of the Desert'

Vladimir Motyl/Lenfilm, 1970

Another cult Soviet film, White Sun of the Desert by Vladimir Motyl (watched by all Russian cosmonauts before every flight), also jokes about the long-lost days of black caviar’s abundance. The hero of the film spoons it out of a huge bowl into his mouth, almost crying because he is so sick of the stuff (the movie is set on the Caspian Sea, where 90 percent of all black caviar in the USSR was produced).

Yet the Russian tradition of decorating the festive table with real caviar is still with us, and today red caviar is a must-have hors d’oeuvre at New Year. Black, meanwhile, remains the preserve of the chosen few, despite the fact that the main salad dish at New Year—Olivier or Russian (as it’s known in the West) salad—was originally dressed with the darker sort.

Learn more about the history of Russia’s edible black gold in our longread, and check out our tips on how to select caviar.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.