Why were the Soviets hellbent on finding U.S.-made Stinger missiles in Afghanistan?

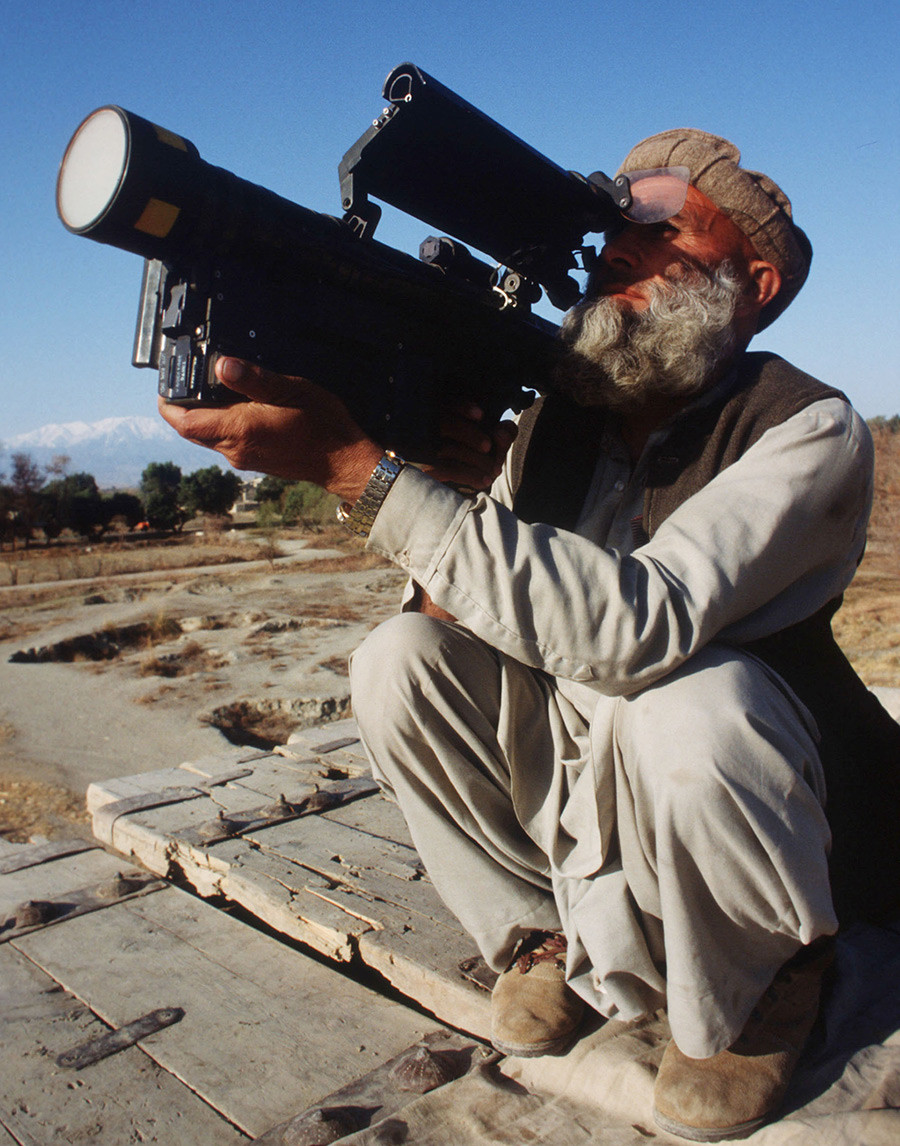

A mujahideen soldier aims a Stinger missle at passing aircraft near a remote fighters' stronghold in the Safed Koh Mountains February 10, 1988 in Afghanistan

Getty ImagesRussia marks 30 years since the pullout of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. It is sometimes claimed that it was the introduction of

By the mid-1980s the Afghan mujahideen, who were fighting both regular Soviet troops and the Soviet-backed government in Kabul alongside Pakistan and the U.S., were in a difficult situation. “In April 1986 hard battles were being fought along the border with Pakistan…I used all means possible to push through my demands [of supplying the mujahideen with Stingers]…I strengthened my argument with the opinion of the U.S. analysts who said the mujahideen could not continue fighting as they were so exhausted that the young generation didn’t want to join the Jihad,” wrote Mohammad Yousaf, a high-ranking Pakistani intelligence officer. As a result, the Americans supplied the mujahideen with arms to fuel their efforts to overthrow the Moscow-backed regime.

Powerful weapon

The decision to back the jihadists was not taken lightly by the Reagan administration, as the Americans didn’t want their weapons technology to fall into the hands of the USSR or Iran. If the Soviets obtained U.S.-made missiles it would have proven that Washington was supplying the mujahideen with state-of-the-art arms. Pakistan took a similar stance. However, in 1986 the U.S. approved a shipment of 250 Stinger launchers plus 1,000 missiles to the Muslim guerilla warriors

The wreckage of an Afghan transportation plane that was hit by a Stinger missile. 40 people onboard died.

Alexandr Graschenkov/SputnikThe portable devices were reportedly used in Afghanistan for the first time on Sept. 25, 1986. A group of around 35 mujahideen shot down two Mi-24 attack helicopters (the Soviet army claimed) when they were landing at Jalalabad Airport. It’s

According to Yousaf, the news about the new weapon and its devastating capacity was met with euphoria by the guerilla fighters. Soviet commanders, however, were incredibly concerned. In November of 1986 the Soviet army lost four Su-25 attack jets, and an entire flying squadron a year later. Many of the USSR’s helicopters were also shot down.

Change of tactics

After these losses, Jalalabad Airport was closed for a month. When it reopened stricter flying rules were enforced. “We had to change our tactics fundamentally. The air force had to fly at a higher altitude, no less than 5,000 meters,” explained military expert Mikhail Khodarenok

A mujahideen holds a stinger March 15, 1989 in Jalalabad, Afghanistan

Getty ImagesA Hero award for the Stinger

To combat the new missiles Soviet engineers needed to examine them up close, so the hunt for Stingers began. Anyone who found the weapon was promised the highest Soviet award – the Hero of the Soviet Union

In total, Soviet special service units managed to get eight sets of the weapon

Andrey Solomonov/SputnikStingers and the Soviet withdrawal

A few years ago another group of former Soviet soldiers, this time headed by Lieutenant Igor Ryumtsev, claimed to be the first to capture a Stinger – at the end of 1986. In total, Soviet special service units managed to get eight sets of the weapon. However, nobody became the proud owner of the USSR’s Hero award then. The injustice was corrected on the 30th anniversary of the Soviet pullout. Kovtun got the title of Hero of Russia for his courage and valor during the conflict in Afghanistan

The Soviet pullout from Afghanistan was over on February 15, 1989

Andrey Solomonov/SputnikAnd it should be known that the introduction of Stingers did not force the USSR to withdraw from Afghanistan, as it is sometimes claimed – this decision was taken in Moscow much earlier.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox