Why did only Russia wind up with nuclear weapons after the USSR collapsed?

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 led to all sorts of problems. It set off the beginning of the so-called "wild 90s," which remain imprinted on post-Soviet society’s memory as a time of poverty, a flourishing Russian Mafia, financial pyramids and the complete loss of national direction. But as it watched the disintegration of a major superpower, the rest of the world was much more preoccupied with the following question: What will happen with all the nuclear weapons?

With Soviet Union’s collapse, its stockpiles of nuclear warheads, which conferred enormous military power but also posed an enormous danger, wound up on what had just become four separate states: Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine.

What should we do?

Initially, Russia’s new president, Boris Yeltsin, declared that Russia would not have single-handed control over the USSR's entire nuclear arsenal. In Almaty on Dec. 21, 1991, all four countries that had inherited the Soviet Union’s nuclear weapons signed a treaty on joint control. Nine days later, representatives of the four countries met again in Minsk and signed another treaty, this one setting up a joint "strategic forces" command.

Leaders of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine declared the death of the Soviet Union and formed a Commonwealth of Independent States.

U. Ivanov/SputnikIt started to seem like the issue had been resolved, but it had not because on Dec. 25, in the period between the two meetings, Mikhail Gorbachev, who had just stepped down as leader of USSR, handed the so-called nuclear briefcase over to Boris Yeltsin. The treaty also stipulated that any decision to launch the nuclear weapons should be made by Russia in legally-binding coordination with the heads of Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Belarus and in consultation with the other member-states of the CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States).

Vilen Tymoshchuk, a colonel stationed in Ukraine at the 43rd Missile Army, one of the most powerful missile units, would say: "Neither the president of Ukraine nor anyone in the country could have had any influence on [nuclear] missile launches because the launch codes would have had to go out from the Central Command Post located in Russia."

This arrangement didn't suit the West and, as would later emerge, from the very beginning it didn't suit Russia either.

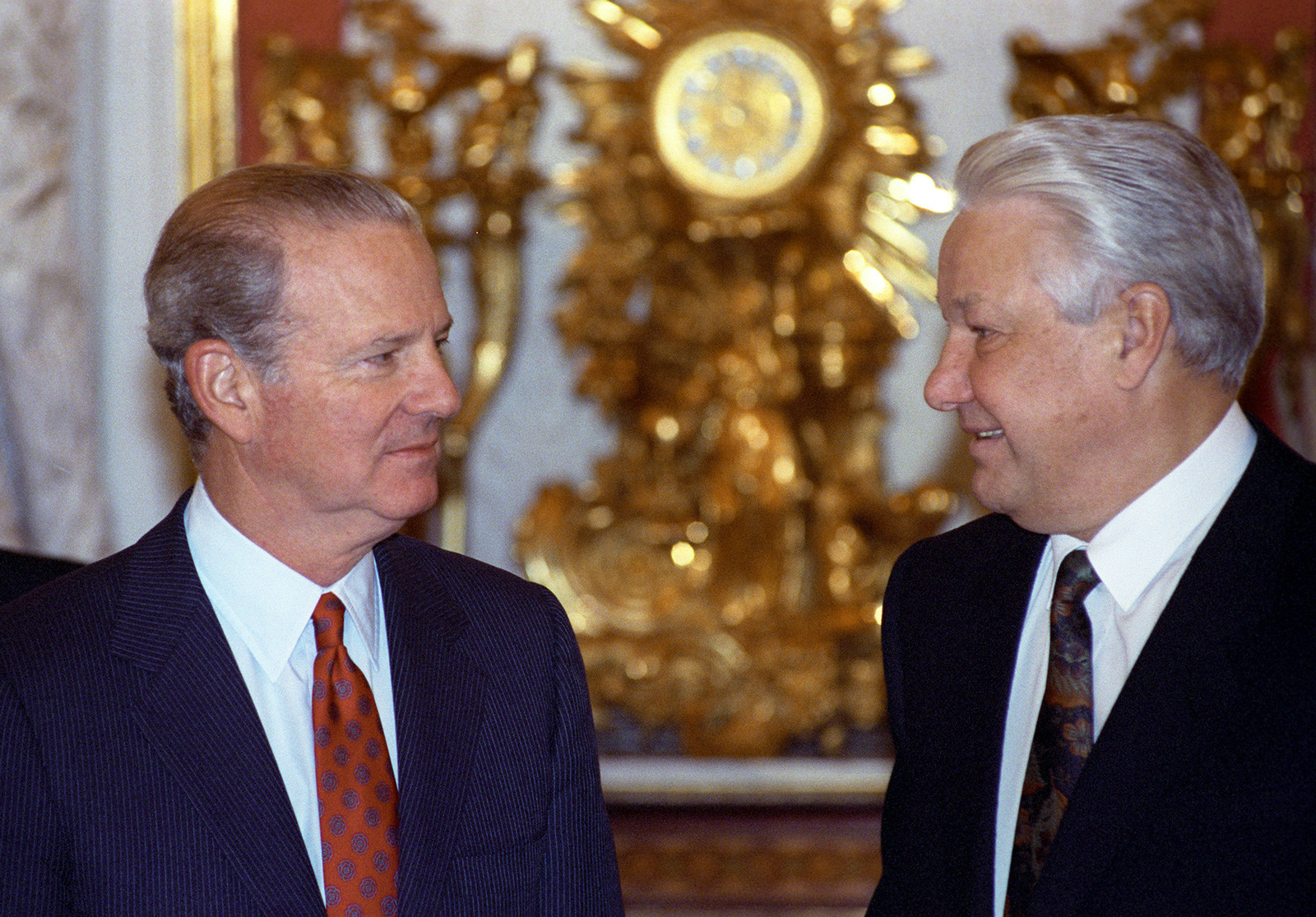

President Boris N. Yeltsin and James Baker, the U.S. Secretary of State

Dmitryi Donskoy/SputnikTalking with the Russian Forbes in 2012 about talks with Yeltsin during that period, James Baker said the following: "Yeltsin, with unprecedented frankness, told me, the U.S. Secretary of State, how the nuclear program and nuclear weapons control would develop within the framework of the Commonwealth of Independent States…Who would have the button and who wouldn't, and what the leaders of Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan thought about it, and that they believed that they would have nuclear weapons while in actual fact they wouldn't."

The United States was the main mediator in the resolution of this nuclear crisis and pushed for a different resolution: that the whole nuclear arsenal remain only in Russia.

"We indeed wanted to deal with one country, not four. We didn't want to end up with four countries possessing nuclear weapons instead of one," Baker noted in the same interview.

But how to convince three countries to give up this enormous power? At talks behind closed doors the phrase “a second Chernobyl" could be heard frequently.

Explosive inheritance

The trouble was that the lifespan of many nuclear warheads stockpiled in the Soviet republics was to expire in 1997. The storage facilities at the time were filled to capacity and ensuring their safe maintenance and dismantling would require significant financial and technological resources. No one possessed either, and so the fear was that in the event of a natural disaster or an emergency all these stockpiles could have blown up.

After the last explosion, which destroyed the last Soviet warhead in Kazakhstan.

Yuriy Kuydin/SputnikAccording to Leonid Kravchuk, Ukraine’s leader at the time, Yeltsin gave him an ultimatum that Russia would no longer accept any "explosive warheads" after 1997 and that they had to be handed over now. In the end, it was relatively easily for the two sides agreed “a barter."

In Belarusian SSR

V. Kiselev/SputnikMeanwhile, Kazakhstan, which had inherited the second largest nuclear test site on the planet at Semipalatinsk, handed over its arsenal without any fuss. Kazakhstan was concerned about safety and at the same time was happy to receive military hardware and investments in return, former President Nursultan Nazarbayev said in an interview with Japanese media. By 1992, everything had been sorted out here.

Belarus signed a treaty on the withdrawal of its arsenal in 1994 in exchange for security guarantees. Granted, it later came to believe it had made a bad deal and regretted this: "It should not have been done, we should have sold this hugely important possession of ours, which was a valuable commodity, for decent money," the country's leader Alexander Lukashenko said.

The main remaining issue was with Ukraine, which didn’t want to give up its nuclear weapons.

The Ukrainian question

Following the collapse of the USSR, Kiev possessed the third most powerful nuclear arsenal in the world after the U.S. and Russia. Intercontinental missiles aimed directly at the U.S., along with 1,240 warheads, had ended up on Ukrainian territory.

"Possessing a nuclear arsenal vulnerable either to a terrorist or someone with an ordinary rocket, we were seemingly sitting on a powder keg, threatening everyone: Dare touch us and we will all be blown to smithereens together," Yuriy Sergeyev, Ukraine's permanent representative to the United Nations, said in an interview with UN Radio on Jan. 20, 2014.

President Boris N. Yeltsin (R) with Leonid Kravchuk (L), Ukraine’s leader

Dmitryi Donskoy/SputnikThis situation was problematic for the U.S. as well. It set a condition. "They said: Unless you do the job of removing warheads from Ukraine, the consequence will be not just pressure but a blockade of Ukraine. Sanctions and blockade—these were the words they bluntly used," Kravchuk said in an explanation (even 25 years later, some supporters of Ukraine having nuclear weapons still blame him for disarmament).

But Ukraine was in a tough spot. "Had Ukraine not given up its nuclear weapons, no one would have recognized it," the Ukrainian parliament speaker Volodymyr Lytvyn said in 2011.

Removing warheads from Ukraine, 1992

Vladimir Solovyev/TASSAnd so it came to pass that in 1994 Kiev signed a memorandum in exchange for territorial integrity and economic assistance. Ukraine received $175 million from the U.S. for the disposal of the nuclear weapons. In 2000, Russia wrote off Ukraine's debt amounting to $1,099 million, although Ukraine had asked for three billion dollars in compensation. But the most important thing is that by the end of 1996 the withdrawal of the nuclear arsenals from the former Soviet republics had been completed, and Russia and the U.S., in accordance with agreements, began the lengthy process of reducing their nuclear arsenals.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox