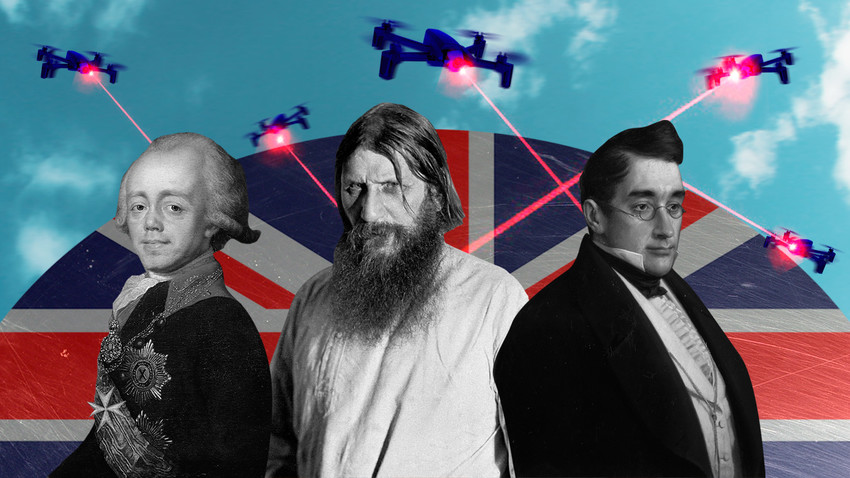

3 successful secret British plots against the Russian Empire

1. Murder of Paul I

Russian Emperor Paul I

Public domainIn the last decade of the 18th century, most European monarchs wanted to destroy revolutionary France in order to prevent its infectious ideas from spreading to their states. Russian Emperor Paul I wasn’t an exception.

As time passed, however, Paul I became very disappointed that the confrontation with the French was yielding no benefit for Russia. While the tsar’s troops were spilling blood and guts, the British and Austrians remained on the sidelines, scooping up the spoils of Russia’s hard-fought victories.

The last straw was Britain’s seizure of Malta in 1800, and after dislodging the French garrison they kept the island for themselves instead of returning it to the Knights of Malta. Paul, who was Grand Master of the order, took this as a personal insult.

To the horror of the British, the Russian emperor dramatically changed the course of his foreign policy. He befriended the former enemy, Napoleon, and together with the French ruler planned a joint campaign into India, the British Empire’s main source of wealth.

“Together with your sovereign, we will change the face of the world!” Napoleon told the Russian envoy in Paris.

The plan called for using over 70,000 French and Russian soldiers to fight the East India Company’s troops in India, and the first force - a Cossack detachment under Ataman Matvey Platov - started their march to the borders of Afghanistan on March 13, 1801.

However, the invasion was fated never to take place. On March 23, 1801, Paul I was murdered as a result of court intrigue in which Britain, and personally the British diplomat Lord Charles Whitworth, played an active role. The British had been financing the plot and even awarded the conspirators with a “bonus” after the deed was done.

One of the first decrees of the new emperor, Alexander I, was to order Platov’s Cossacks to return home. Soon, Russia and Great Britain were allies again.

Napoleon reacted furiously to the death of his Russian ally: “They missed me on the third of Nivôse [the fourth month of the French Republican calendar, and a reference to an attempt on Napoleon’s life on Dec. 24, 1800, in which the British were implicated], but got me in St. Petersburg.”

2. Massacre of Russian embassy in Tehran

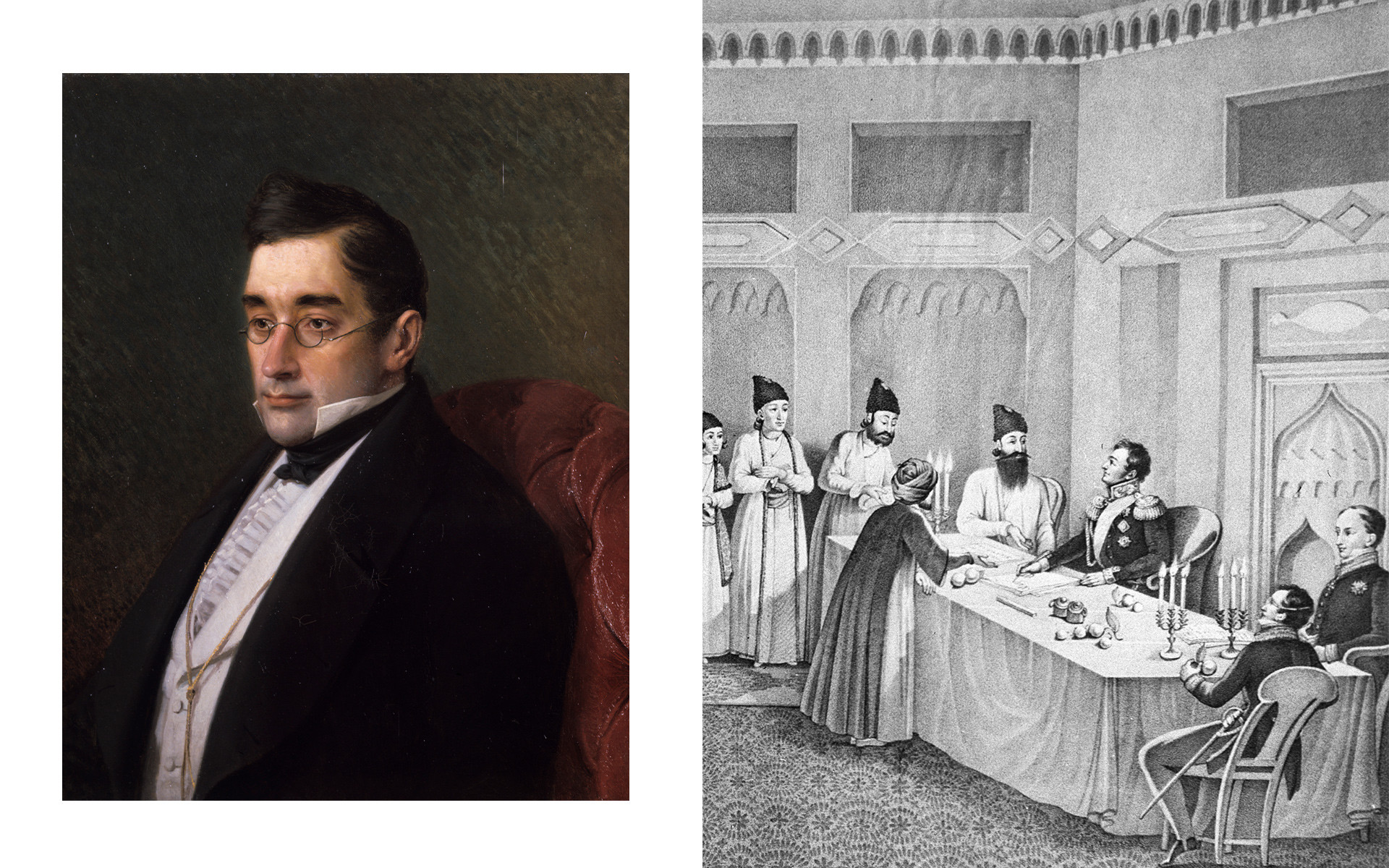

Alexander Griboyedov

Pavel Balabanov/SputnikOn the early morning of February 11, 1829, an enormous horde of almost 100,000 Persians, armed with knives, stones and sticks, attacked the Russian embassy in Tehran, which was guarded only by 35 Cossacks. The Persians literally tore apart the Russians, who included the ambassador himself, the great poet Alexander Griboyedov.

This crime was precipitated by the fact that the Russians provided refuge to the local Armenians who fled to their historical homeland, a part of the Russian Empire. One such Armenian was not a common man. Jakub Markaryan Mirza, who served as a eunuch in the Shah’s harem, was also the main treasurer and keeper of the Shah’s jewellery. He knew too many secrets to be allowed to flee to an enemy state.

After all requests to return Markaryan Mirza were refused by Griboyedov, the Persian ruler, Fath-Ali Shah Qajar, ordered to incite the mob, which was already outraged by the country’s recent defeat in yet another Russo-Persian war. The angry mob killed the Russians and Makaryan, who had found shelter at the embassy.

Many believed that the British stood behind the cruel plan that inspired the Persians. The Russian and British empires were locked in the “Great Game” for dominance in Central Asia, and a new Persian-Russian war would help them greatly.

“Now the Englishmen are triumphing, assuring the Persians that we (Russians), being in the vigilante war against Turkey, can’t do anything to them. They say that England will soon declare war on Russia and advise crown prince Abbas Mirza to attack our border regions,” wrote the only survivor of the Tehran massacre, secretary Ivan Maltsov, in a letter to Russian Foreign Minister Karl Nesselrode.

The Shah, however, wanted just to kill Makaryan Mirza, not to launch a new war. Russia remained stuck in the war against the Ottomans and wished to avoid a conflict with Persia. That’s why the incident was hushed up.

3. Murder of Rasputin

Left: Oswald Rayner. Right: Rasputin with the Romanov family

Public domainWhile the British role in the assassination of Griboyedov and Paul I remained in the shadows, the murder of Grigory Rasputin was made with active and outright British participation.

One of the most mystical figures in Russian history, Rasputin was a favorite of Empress Alexandra, and significantly influenced the entire Romanov family. By 1916, Rasputin had gained such power that he directly advised Emperor Nikolai how to conduct the war.

This was unacceptable among the emperor's circle, which realized what catastrophe could result from the activity of this “holy man.” When Nikolai dismissed all demands and requests to remove Rasputin, the conspirators began to act.

The big question, of course, is what role the British played in this plot: whether they completely organized it themselves, or just joined it. In any case, Great Britain would certainly benefit from Rasputin’s assassination.

The secret intelligence service (SIS) was sure that Rasputin was a German agent. They feared that “Dark Forces” (a codename for Rasputin) and his patron, Empress Alexandra, ( of German origin) were preparing a separate peace with Germany, as well as Russia’s exit from the war.

Whatever the reasons, the British dealt the final blow. It is believed that the kill shot into Rasputin's head was made by a British SIS agent, Oswald Rayner, who along with the Russian conspirators ended the life of the “mad monk” on December 30, 1916.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox