This dissident exposed the horrors of Soviet ‘punitive psychiatry’

Vladimir Bukovsky (1942 - 2019).

APAn unusual exchange took place at Zürich airport in December 1976. , Chile and the USSR, with assistance from the U.S., exchanged Luis Alberto Corvalán, the general secretary of the Chilean Communist Party (imprisoned by the government of Augusto Pinochet) for Vladimir Bukovsky, a 35-year-old inmate of the Vladimir Central Prison. Corvalán flew to Moscow and Bukovsky stayed in the West.

Corvalán was a prominent communist politician, whilst Bukovsky, labeled by the Soviet press as “hooligan”, held no office and seemed to be an ordinary Soviet prisoner. His fellow dissident Vadim Delaunay even wrote an epigram on the occasion:

They exchanged a hooligan for Luis Corvalán:

What kind of bitch do you think we could switch for Brezhnev?

But jokes aside, what was so important about that “hooligan” Bukovsky?

‘Sluggish schizophrenia’

Young Bukovsky.

vladimirbukovsky.comBorn into a family of a Soviet journalist, Vladimir Bukovsky had been openly skeptical of Soviet society since his teenage years – and that wasn’t safe in the USSR. In 1960, Bukovsky wrote an article, harshly criticizing the Komsomol (Soviet youth organization): “The Komsomol is dead. Its embalmed corpse has been confused for a living body for far too long…”

Bukovsky called for the democratization of the organization – but the authorities responded with repression. In 1962, Bukovsky was diagnosed with sluggish schizophrenia - a very ‘Soviet’ disease developed in the 1960s by the psychiatrist Andrei Snezhnevsky.

“Most countries of the world didn’t recognize such a disease. But it was very convenient for the KGB to allow any person to be declared insane, even without any symptoms [of schizophrenia] – the absence of which was being explained by the disease’s slow progression,” Arzamas writes. Portraying dissidents as mentally ill was the instrument of the so-called Soviet punitive psychiatry, a phenomenon that Bukovsky would later reveal to the world.

Severe years

Special psychiatric hospital, where Vladimir Bukovsky was detained.

Pavel Markin/Global Look PressBukovsky spent most of the 1960s behind bars: Soviet psychiatry was changing its mind over his diagnosis, declaring him insane or sane on different occasions, sending him to asylums (1963, 1965) or prison camps (1967). In his memoirs he described living conditions in mental asylums as horrifying: people were severely drugged, sometimes beaten and tortured, as well as put in the same cells with actual dangerous mental patients.

When Bukovsky was released from prison in 1969, there were several other people declared mentally ill, and institutionalized, due to their politics: Natalya Gorbanevskaya, who protested against the Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968, and General Petr Grigorenko, a World War II veteran who criticized the communist party, were among those names.

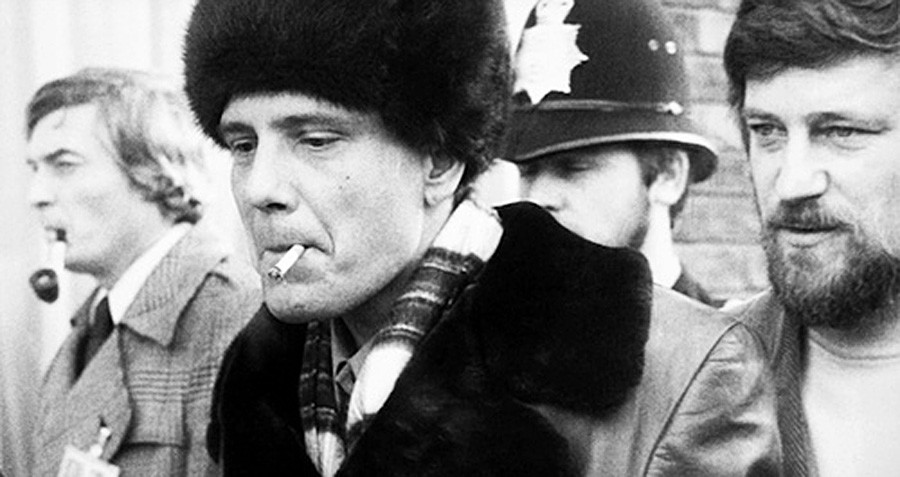

Vladimir Bukovsky after his release in 1976.

vladimirbukovsky.com“In total, there were around six people [put in asylums]. I understood that there is a [punitive psychiatry] system working. Something should have been done,” Bukovsky recalled in an interview. He secretly met with American journalist William Cole of CBS, and gave a live interview on the incarceration of dissidents under the pretext of mental illness. He also managed to smuggle multiple materials on the matter to the West.

In 1971, Soviet authorities arrested Bukovsky again, tried and found him guilty of anti-Soviet agitation. He was imprisoned for seven years – however, as we know, his term was cut short by the exchange for Corvalán. By 1976, the West considered him an important dissident figure and an outstanding human rights activist.

Later life

Bukovsky meets the U.S. President Jimmy Carter in 1977.

vladimirbukovsky.comBukovsky settled down in the UK, gaining a master's degree in biology from Cambridge University and writing several memoirs, the most famous of which is called To Build a Castle: My Life as a Dissenter. As an émigré, he remained one of the harshest critics of the USSR and its policies: for instance, he supported the boycott of the Moscow Olympics in 1980. Later, as the USSR fell apart, Bukovsky called for conducting a trial similar to the Nuremberg one, officially denouncing communism.

He was disappointed after that didn’t happen, writing: “Having failed to finish off conclusively the communist system, we are now in danger of integrating the resulting monster into our world.” He continued to criticize the new Russian leaders as well - first Boris Yeltsin, then Vladimir Putin.

Soviet-era dissident Vladimir Bukovsky attends a meeting with his supporters in Moscow, Russia in 2007.

APHis homeland, however, was not the only target of Bukovsky’s bashing – for instance, he denounced the EU as a “monster” and a quasi-totalitarian system. “I think that the European Union, like the Soviet Union, cannot be democratized,” Bukovsky toldThe Brussels Journal, implying that the EU as a structure should be destroyed.

Scandal

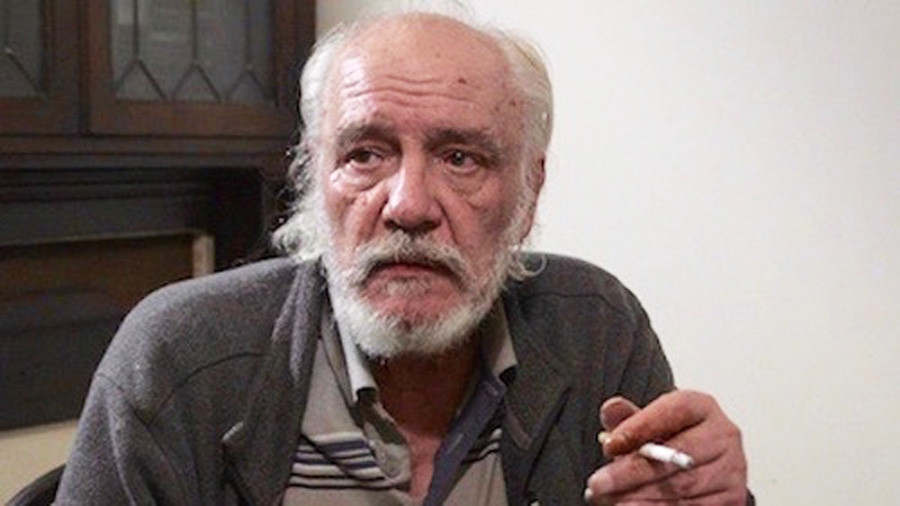

Bukovsky at 73.

vladimirbukovsky.comIn 2015, 74-year-old Bukovsky came into the spotlight again – but not because of his human rights activism or writings. The veteran dissident was charged with downloading and possessing more than 20,000 indecent images of children. Bukovsky, in his turn, issued a High Court writ for libel, claiming that the UK Crown Prosecution Service had defamed him. Bukovsky’s claim, though, was dismissed.

“I don’t care about the risk of being sent to prison. I have already spent 12 years in Soviet prisons. I don’t expect to live very long, and it makes little difference to me whether I spend the final few weeks of my life in jail,” the dissident said.

The court decided to postpone the trial indefinitely because of the defendant’s poor health: by that time, Bukovsky had been suffering from multiple diseases.

He never recovered sufficiently to stand before the court again. On October 27, 2019, the dissident succumbed to heart failure, taking both his legacy and controversy to the grave.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox