Why were there so many Germans in the Russian Empire?

In Moscow, a myth still persists that many 1950s apartment buildings "were built by captured Germans". And even though by 1950 most of the Germans captured during the war had already been repatriated to their homeland and didn't build any houses, the myth lives on, primarily thanks to the time-honored mantra of "German quality". And it’s all because Russians and Germans can be regarded as twin nations since the 15th-16th centuries.

With Cross and Sword

A Teutonic Knight on the left and a Swordbrother on the right.

Münchener Bilderbogen/Braun & Schneider, 1870Of course, it all started with conquest. In 1147, when Russian lands were just beginning to take shape and Moscow was a small, albeit powerful, stronghold, Saxon princes mounted the Wendish Crusade, the purpose of which was to convert the pagan Baltic tribes to Christianity and subjugate them. The army of some Russian prince – it is difficult now to establish exactly who he was – also took part in the campaign, since Russians, who were by then Christian, pursued their own agenda in the Baltic region.

This is how Konrad I of Masovia and his wife could look like (19th-century reconstruction)

Jan MatejkoWhen in the 13th century Polish Duke Konrad I of Masovia (Konrad I Mazowiecki) asked the Teutonic Order for help in the war against Prussian pagans who kept seizing Polish lands, it was, oddly enough, his Russian wife from the Rurik dynasty, Agafia Svyatoslavna of Rus, who gave him the idea of inviting the Teutons. Several centuries later the Russians, in turn, would have to fight against the knights of the Livonian Order, which was a branch of the Teutonic Order.

The Germans in the Baltic countries were mainly the ruling aristocratic elite and did not venture into Russia. But from the 15th century, Moscow began to free itself from the political authority of the Golden Horde and to unite Russian lands, which meant that the Moscow princes needed the experienced warriors, engineers, and scientists for which the German lands were famous.

In search of fortune, rank, and price

Vasiliy III, Grand Prince of Moscow

Public domainThere is some confusion about the Germans in 17th-century Russia: The Russians used the word "nemtsy" (немцы) to describe not just Germans but also the French and British, as well as Swedes, Dutch and many others. The Russians "reserved" a special word only for Italians – they called them the "fryazi" or "fryaziny". All other Western Europeans were called "nemtsy" from the Russian word "nemoy" (немой) meaning "mute" – because the foreigners didn't speak Russian! So it is not easy to list all those who came from the German lands and served at the courts of Ivan III ("the Great") and Vasili III – some nemtsy were Germans, and some were not.

But we do know that the Moscow princes needed gunsmiths, military engineers, sappers, and artillerymen, as well as specialists in mining. It is known that two German miners invited to Russia in 1491 discovered deposits of silver ore in the Pechora region (Russian North). Also, Moscow didn't have qualified doctors and pharmacists. Physicians Niсolaus Bülow and Theophil Marquart from Lübeck lived at the court of the Moscow princes in the 15th-16th centuries.

Under Ivan IV Vasilyevich [Ivan the Terrible] the first Nemetskaya Sloboda [German, but also "Foreign", Quarter] appeared in Moscow. In 1551 Ivan sent his agent Hans Schlitte to the German lands, where he recruited 123 people wishing to work in Russia. They were physicians and pharmacists, theologians and legal experts, architects and masons, goldsmiths, specialists in bell casting, and even a couple of professional musicians! Later, during the Livonian War, the German population of the towns conquered by Moscow also settled in Russian lands. And some of the German mercenaries even acquired widespread fame (as well as notoriety) – for example, the German adventurer Heinrich von Staden, who served in Tsar Ivan's oprichnina army [involved in repressions against the boyars, or Russian aristocracy].

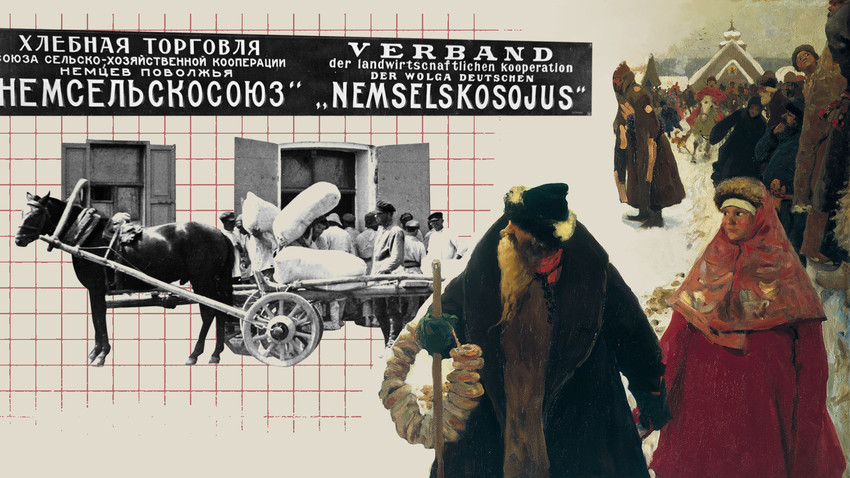

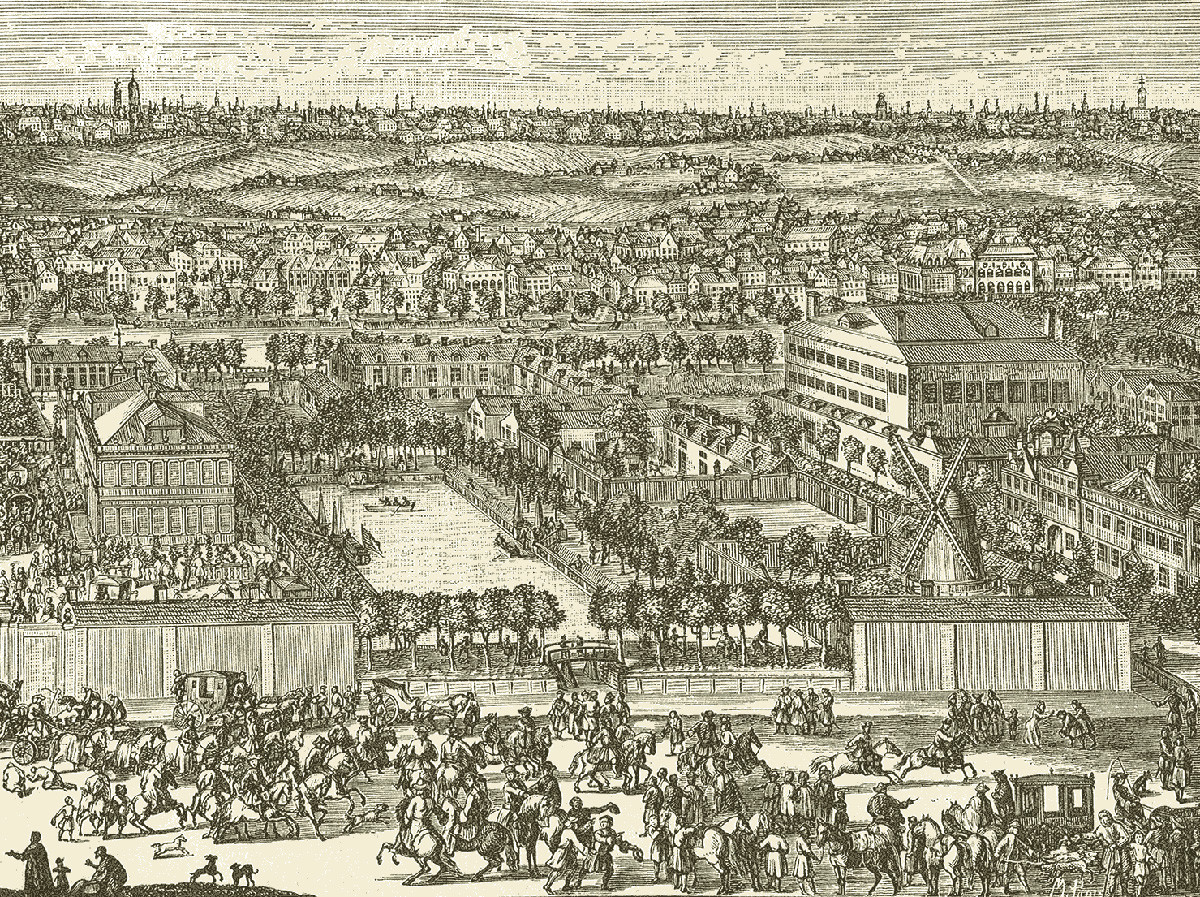

The German Quarter in Moscow in the early 18th century

History of Peter the Great, A. Brickner/A. S. Suvorin Publishing, 1882-1883Following the death of Ivan the Terrible, under Boris Godunov, more and more German merchants came to Russia and a new German Quarter sprang up on the River Yauza in Moscow. By the mid 17th century there were so many Germans that Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich [Alexis of Russia] restricted their right to buy houses and lands from the Russian population – he feared that the enterprising and hardworking Germans would leave Russians without roofs over their heads.

The Germans lived in a closely-knit community in the German Quarter. They adhered to Lutheranism, had their own church and held their own celebrations. The houses in the German Quarter were built in a European style – with sloping peaked roofs and front gardens decorated with flower beds, wooden arbors and ponds. The locals wore European dress and had a Western European lifestyle. And although the British, Dutch, Danish, Swiss, French and Swedes also lived there, German was the main language of communication.

Among the prominent residents of the German Quarter were physician Lavrenty Blumentrost, jeweler Yuri Forbos, pharmacist Johann Guttemensch, pastor Johann Gottfried Gregory, who played a major role in the history of Russian theater, and Geneva-born General Franz Lefort. The latter played an enormous role in Russian history, making friends with the young Tsar Peter, who would soon become Peter the Great.

Germanophile tsars

Franz Lefort

Vadim Nekrasov/Global Look PressFranz Lefort, along with the Scottish General Patrick Gordon, became the first and best friends of the young tsar, who often visited the German Quarter – Peter inherited from his father a love and passion for everything European. Thanks to Peter, who went to Europe with the Grand Embassy in 1697-1698 to recruit foreign engineers and military personnel, a new stream of foreign civil servants and mercenaries poured into Russia.

Financier Heinrich Claus von Fick, barons Georg Gustav von Rosen and Carl Ewald von Rönne (both were generals), poet and translator Johann Werner Paus, military officer and future chancellor Andrey (Heinrich Johann Friedrich) Ostermann, fearless Field Marshal and politician Count Burkhard Christoph von Münnich, engineer and Field Marshal Georg Wilhelm de Gennin, General Johann Weisbach and General Adam Weide... These Germans were friends and allies of Peter the Great and presided over the beginnings of the Russian Empire and did a lot for its glory. Often coming from quite poor families, they were proof of the main principle Peter espoused: It is not noble origin and nationality but talent and merit that make a person's name in the service of Russia.

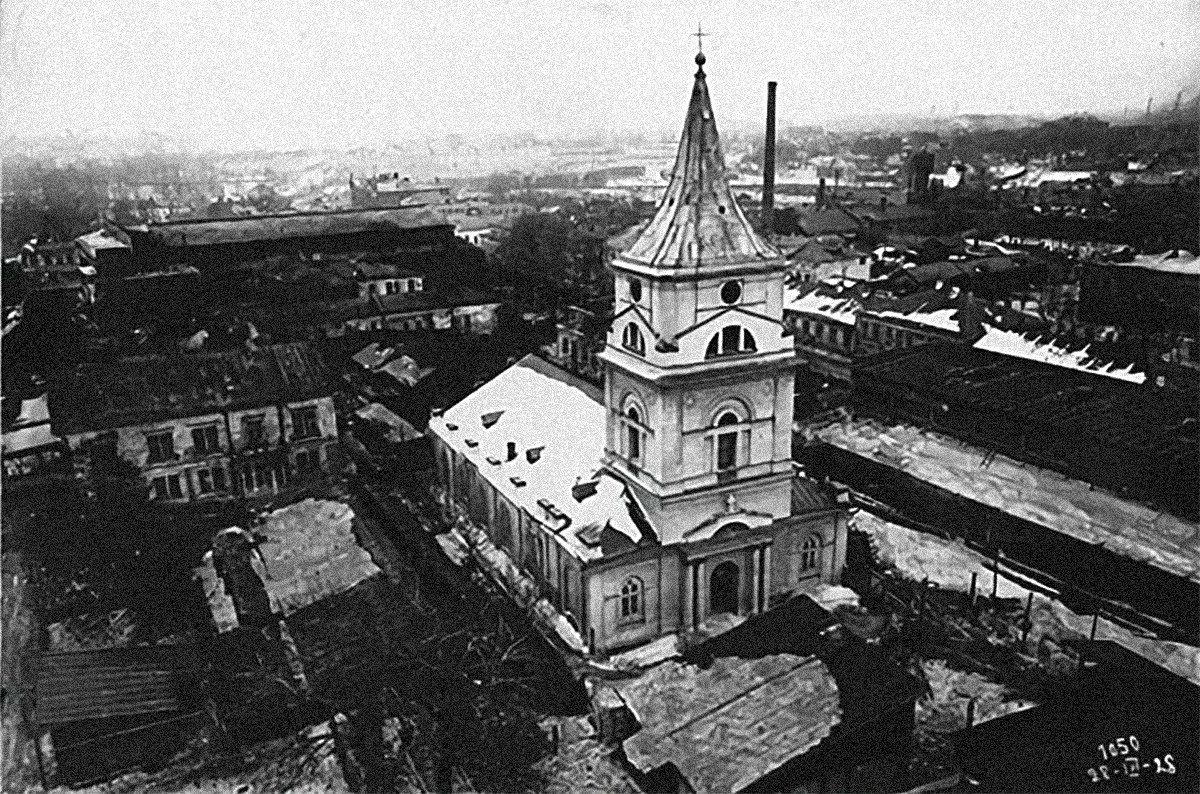

The Lutheran Church of St. Michael (Michael-Kirche) in the German Quarter in Moscow. Demolished in 1928.`

Archive photoThe state system built by Peter, and in particular the Table of Ranks – a list of government, military, naval, and court positions and ranks of the Russian Empire – was practically copied from German models. Therefore the Germans "felt at home" in Russia's service.

Catherine the Great followed in Peter's footsteps: An ethnic German, she came to power in Russia as the consort of Emperor Peter III (also a German) and then seized full power as the result of a coup. In 1762-1763, immediately upon ascending the throne, Catherine issued two manifestos inviting foreign colonists to settle in Russia. The government promised those who wanted to do so a "relocation allowance" for moving and settling in Russia. They were granted personal liberty, freedom of movement and religion, and exemption from paying duties and, most importantly, from military service. The German principalities at this time were constantly waging war and, to escape them, Germans liable for military service fled to Russia with their families. As for Catherine, she invited them to Russia for a different reason: The country was short of peasants to work the land and provide food for the army, so Catherine hoped to improve the situation with the help of the colonists.

July 19, 2013, Saratov region, Russia. The 250th-anniversary celebrations of the publication of Manifesto of Empress Catherine II 'On inviting foreign settlers'. Placing the flowers at the monument to 'Russian Germans who were victims of repression in the USSR'.

Nikolay Titov/Global Look PressThe first "batch" of colonists, numbering about 25,000 people, were sent to the Volga region. The conditions of travel were terrible and not something the Germans were used to – about one in 10 never reached their destination. Nevertheless, more than 100 German villages soon sprang up in the Volga region.

The next "wave" of immigration followed after the 1804 manifesto of Alexander I – once again, the Emperor invited Germans to settle on vacant lands. In Russia during the 18th and 19th centuries Germans settled in the Volga region, Kazakhstan, the Don region, Crimea and Ukraine, and these were just the largest diasporas. As of 1913, about 2.5 million ethnic Germans lived in the Russian Empire, not to mention Russified Germans and their descendants!

Pavlodar, Kazakhstan. Lidia Mertes (L) shows Alena Schmidt (R) how to operate an old spinning-wheel. The Germans living in Kazakhstan stick to the national cultural traditions and customs. German folklore groups, ethnic museums, and national schools function in every district of the country.

Nikolai Kuznetsov/TASSEach diaspora of Russian Germans has its own history, its ups and downs. For 18 years, the German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic existed in the Volga region as part of the USSR, and in 1918 Crimean Germans even attempted to set up their own state. But all these are topics for another day. What is certain is that the histories of the Russian and German people are inextricably intertwined and it is simply impossible to imagine one without the other.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox