7 foreigners who CHANGED Russia

1. Vitus Bering (1681 – 1741), navigator – Denmark

Vitus Bering (a reconstructed image)

Institute of Archaeology of Russian Academy of SciencesBering became the man who carried out one of the last orders of Tsar Peter the Great. Shortly before his death, in January 1725, Peter wrote a secret instruction, whereby Bering was to discover a strait between Asia and North America, and then go down along the North American coast to the south.

Bering, who was born in Denmark, served in the Russian Navy from its inception in 1703, and in 1725, he was already a 1st rank captain. His expedition became the first scientific sea expedition in Russia. In 1725-1727, having arrived in Kamchatka by land, Bering and his crew sailed through the Bering Strait and reached the Chukchi Sea, showing that Asia and America were not connected by land. That expedition discovered the northeast coast of Asia, but it never reached America.

Peter's will was finally fulfilled in 1741, when captain Bering, who was 60 at the time, reached American shores. That also became his last achievement: on the way back, in harsh winter conditions, Bering died on an island, which was later named after him. His remains were found and identified only in the 1990s.

2. Domenico Trezzini (1670 – 1734), chief architect of St. Petersburg – Switzerland

Domenico Trezzini

Public DomainDomenico Trezzini was born in the canton of Ticino in Switzerland. Remarkably, people born there were famous throughout Europe as skilled builders and masons. At the age of 33, having worked in Europe, Trezzini signed a contract to go to work in Russia, where Peter the Great had just founded Petersburg.

The monument to Domenico Trezzini in St. Petersburg, by P. Ignatyev

Nadezhda Pivovarova (CC BY-SA 3.0)As the most experienced of all the architects invited by Peter, Trezzini became the main architect of the new capital. He monitored the construction of several dozen buildings at the same time, and it is his taste that defined St. Petersburg's distinctive look. He is the author of the Peter and Paul Cathedral and of the Twelve Collegia Building, housing Russia's first ministries. Trezzini also compiled a collection of typical designs for residential buildings and country houses, thus setting the architectural style of St. Petersburg for years to come.

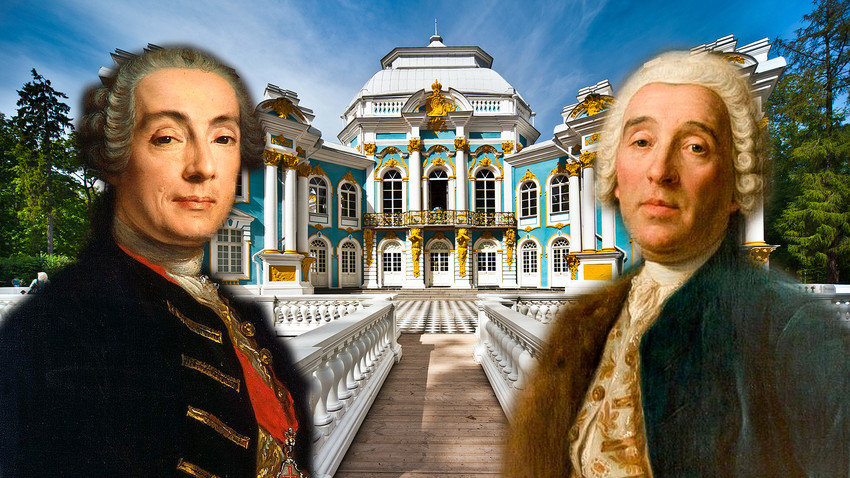

3. Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli (1700–1771), architect, the designer of the Winter Palace – Italy

Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli

Lucas Conrad Pfandzelt/Hermitage MuseumAn Italian born in Paris, Bartolomeo Rastrelli grew up in Russia. His father, the sculptor and engineer Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli, was invited by Peter the Great to Petersburg in 1716.

It was his father who became Bartolomeo's first teacher. The young man also expanded his knowledge by travelling to Europe. The young architect's very first commissions were already of regal level: he designed the Rundale and Jelgava palaces for Duke Biron, a favorite of Empress Anna Ioannovna. The magnificent Rundale Palace features prominently in the HBO series Catherine the Great, with most of the palace scenes shot there. Why? Because it is the closest to the actual palaces of the Russian tsars, the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg and the Grand Palace in Peterhof, both of which were designed by Rastrelli.

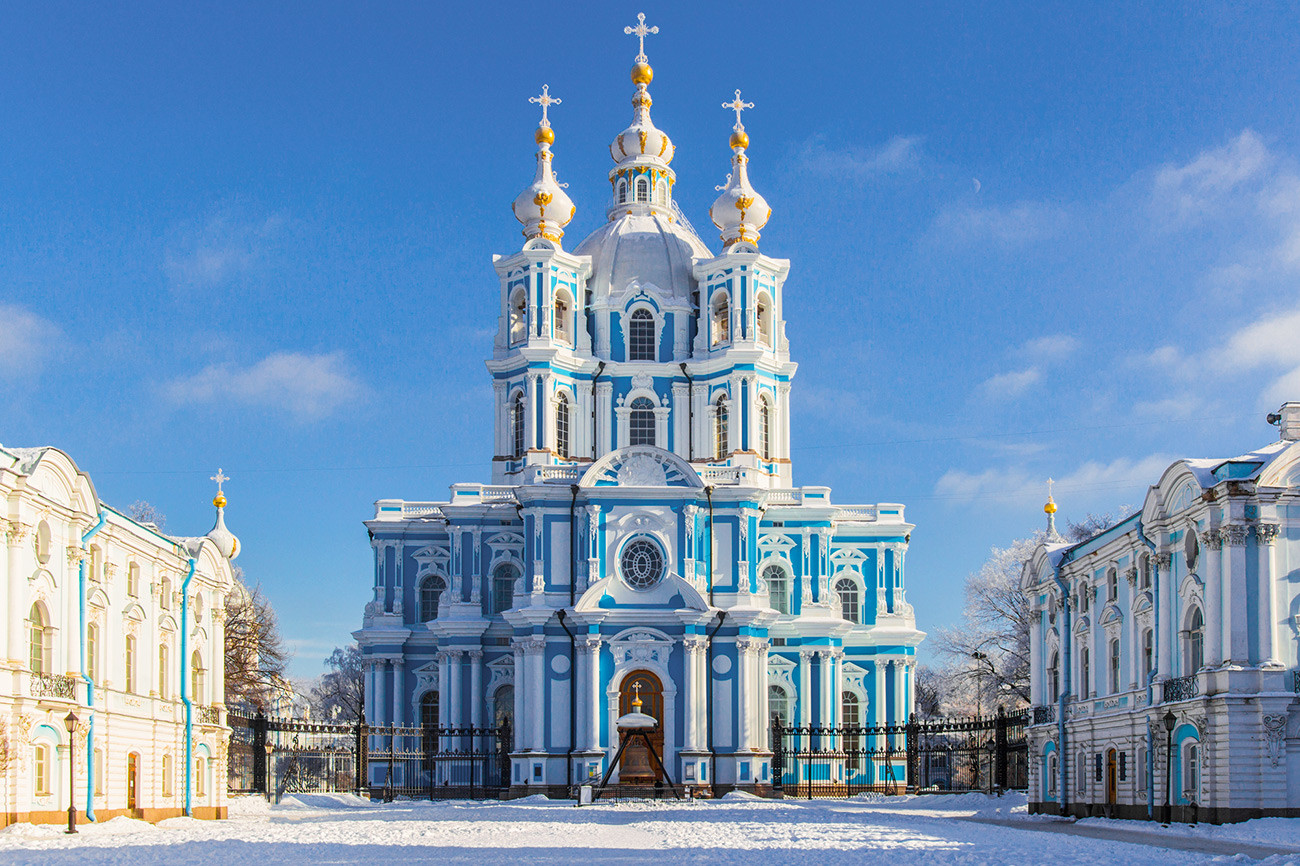

The Smolny Cathedral by F. B. Rastrelli

Legion MediaRastrelli had a unique approach to work: it is known that he himself negotiated with carpenters, masons, potters, and suppliers of materials. Having become the chief architect of the Russian court, he managed several projects simultaneously, but each of them was marked by his unique and recognizable style, which became known as 'Elizabethan Baroque'. In addition to his palaces, Rastrelli is also known for designing the Smolny Cathedral in St. Petersburg and St. Andrew's Church in Kiev, other fine examples of baroque architecture.

And it was the baroque that also ruined Rastrelli when it went out of fashion and commissions stopped. The architect, who was used to a luxury lifestyle, very soon went bankrupt. He tried to flee Russia and offer his services to Frederick II, but he, too, was not interested in an outdated architectural style. So Rastrelli returned to Russia. To make ends meet, he sold furniture and artworks from his home. The exact place and time of his death is unknown.

4. Agustín de Betancourt (1758 – 1824), engineer – Spain

Agustin de Betancourt

St.Isaac's Cathedral MuseumAgustin de Betancourt first became famous in his homeland of Spain. A descendant of a noble family, he trained as an engineer at the best universities in Europe. In 1798, Agustin set up Spain's first telegraph line and later became the head of the Spanish Corps of Engineers. However, Spain was struck by an economic and political crisis soon after, and a war was looming in the air. Betancourt had to flee the country. It seemed his brilliant career was over. But in 1808, he was invited to Russia, where he was immediately granted the rank of a Major General and offered unlimited opportunities: Russia was desperately short of engineering talents.

Betancourt, who is little known inside Russia, has, in fact, left a huge mark on various aspects of Russian life. He was the first director of the State Paper Procurement Expedition, and most of the machines for printing Russian banknotes at the time were created by Betancourt. He also became the first head of the Russian Institute of Railway Engineers, overseeing the training of specialists who later began the construction of Russia's first railway.

Raising of the Alexander Column in 1832. Russia, St Petersburg

Bichebois, Louis-Philippe-Pierre-Alphonse; Bayot, Adolphe Jean Baptiste.Yet, Betancourt's main legacy is known to every Russian – it is the Alexander Column in St. Petersburg. It was according to a system developed by Betancourt that his student, the sculptor Auguste de Montferrand, managed to put the 600-ton granite monolith upright.

5. Auguste de Montferrand (1786 – 1858), architect, the designer of St. Isaac's Cathedral – France

Henri Louis Auguste Ricard de Montferrand by Eugène Pluchart, 1834

Eugène PluchartAuguste de Montferrand served in Napoleon's army, but his career began when he presented an album of his architectural designs to the Russian Emperor Alexander I, after his victorious army entered Paris in 1814. Alexander liked the designs, and the 30-year-old architect was soon invited to St. Petersburg. There, he met with Agustin de Betancourt, who was serving as the chairman of the St. Petersburg urban planning committee.

St.Isaac's. Bust of Auguste de Montferran

A. C. Tatarinov - (CC BY-SA 3.0)Betancourt discerned an extraordinary talent in the young architect and, at his own risk, suggested nominating Montferrand as the architect in charge of the reconstruction of St. Isaac's Cathedral to the emperor. This cathedral was one of St. Petersburg's holiest sites: it was founded under Peter the Great, and it was there that Peter married Empress Catherine. Furthermore, the reconstruction work was extremely complex: the existing cathedral had to be partially dismantled and, without touching the three consecrated altars, be built into a new structure.

St. Isaac's Cathedral in St. Petersburg

Legion MediaMontferrand spent his whole life on this project: the new cathedral was completed in 1858, and a month later the architect died. His last wish was to be buried in the cathedral's crypt, but Emperor Alexander II did not give permission for this, since Montferrand was a Catholic. Instead, the coffin with Montferrand's body was taken around the cathedral three times, and a Montferrand bust was placed inside the building, instead. The bust is made of fragments of stones used to decorate St. Isaac's Cathedral. Montferrand’s body was returned to France and buried in the Cimetière de Montmartre, Paris, next to his mother.

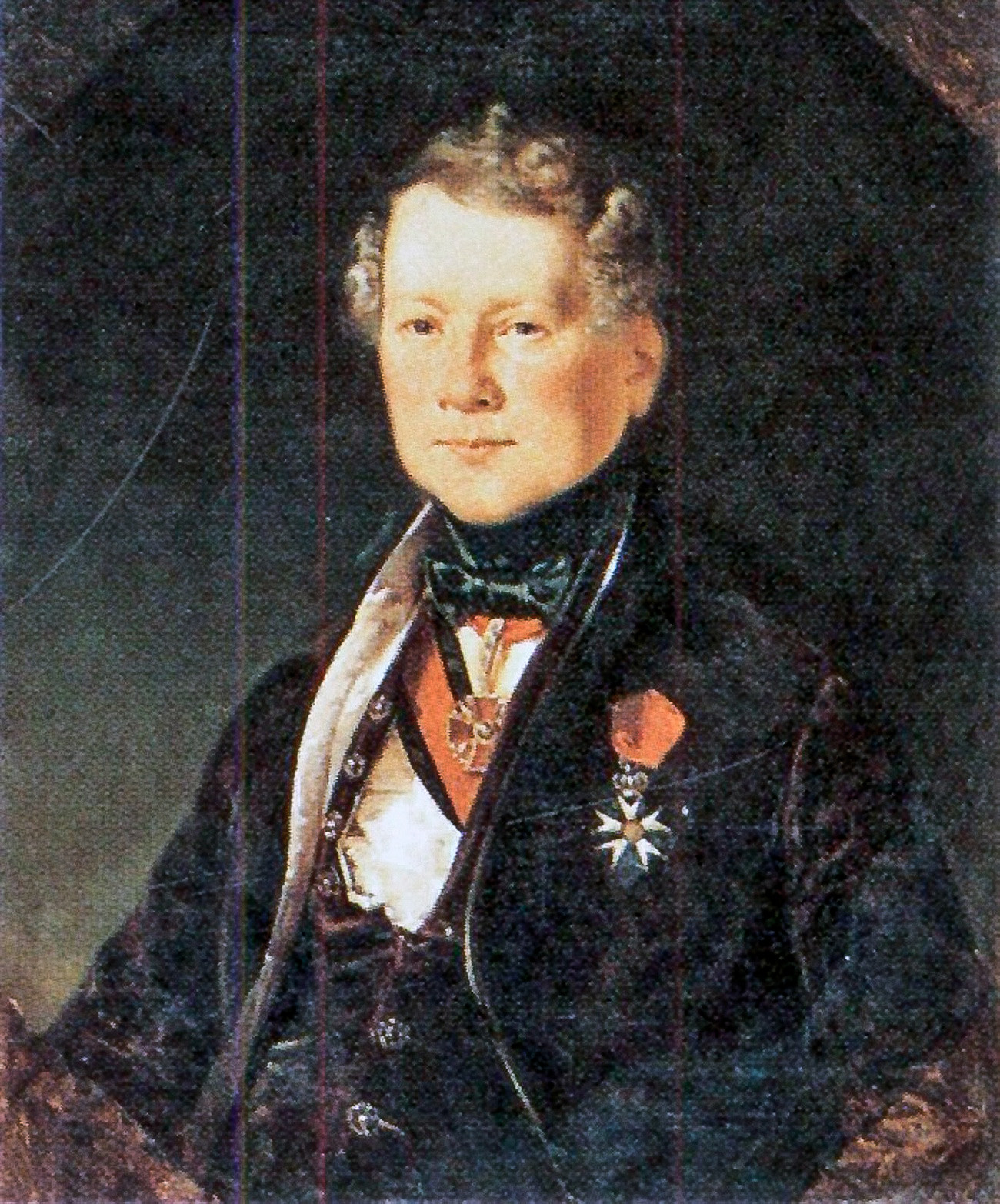

6. Moritz Hermann von Jacobi (1801 – 1874), physicist, inventor of electrotyping – Germany

Moritz Hermann (Boris) von Jacobi

Rudolph HoffmannThe domes of St. Isaac's Cathedral, who were created by Montferrand, were gilded with the use of mercury vapors, killing from 60 to 100 craftsmen in the process. It was physicist Boris (originally Moritz) Jacobi who had invented electrotyping, a technology that allowed objects to be coated with metals using an electric current. This technology was used to gild smaller elements of St. Isaac's Cathedral decorations.

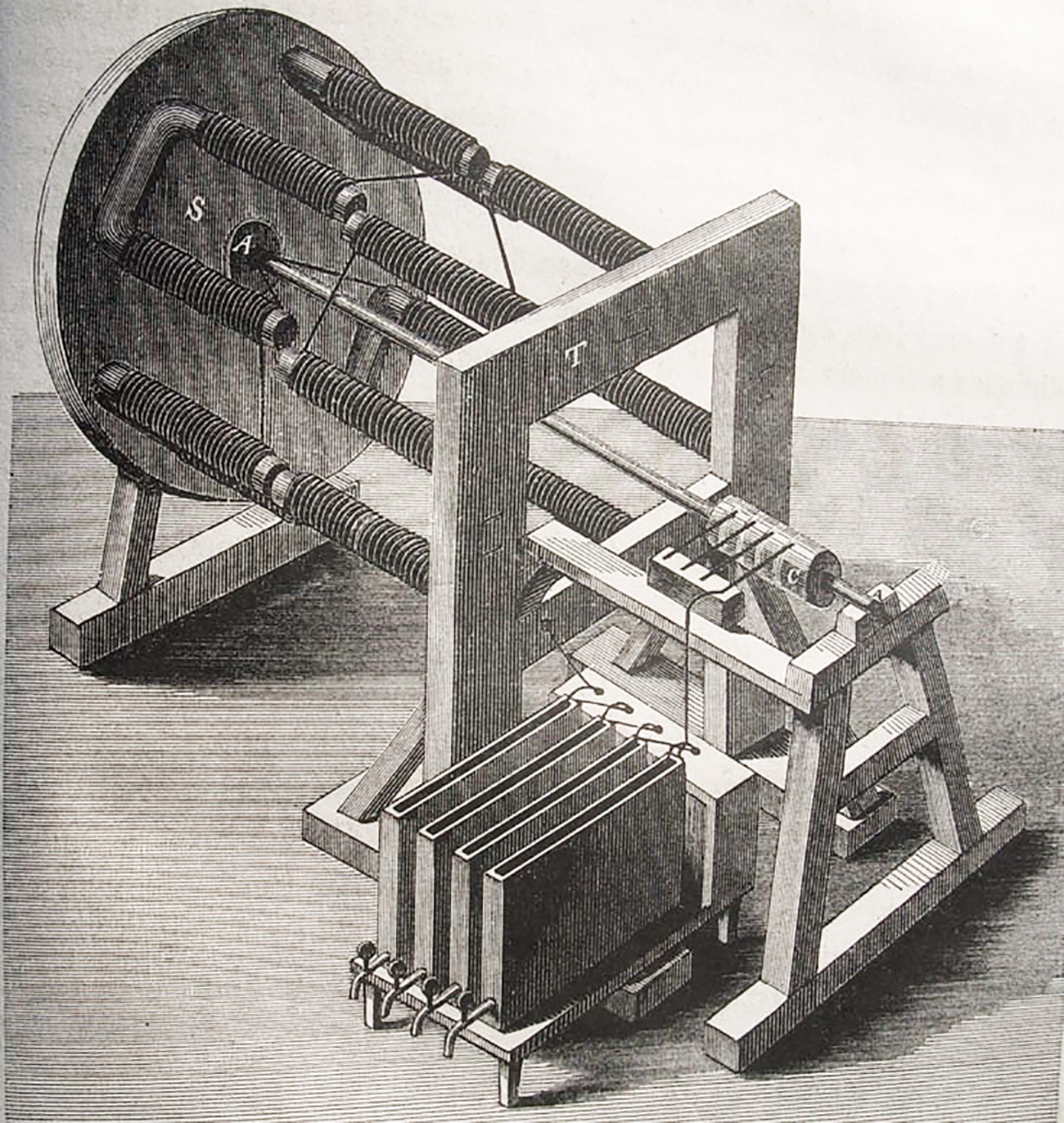

Jacobi's electric engine

Julius DubBoris (Moritz) Jacobi was born in Potsdam to a wealthy Jewish family. His father was a personal accountant to the king of Prussia, so Moritz received an excellent education in engineering. His main interest was electricity and in 1834, he assembled the world's first electric motor. That happened in Koenigsberg, not far from Russia, and Jacobi was invited to live and work in Russia: Emperor Nicholas I saw great potential in the technology created by Jacobi.

Moritz Jacobi moved to Russia in 1837 and, as it turned out, for good. In St. Petersburg, he was treated like a celebrity: immediately upon arrival, he was allocated 50,000 rubles (the equivalent of the annual salary of 10 ministers) for research and development, and Jacobi did not disappoint. Already in 1838, he came up with his main invention - electrotyping. In 1841, Jacobi made the first type-printing telegraph for the Russian tsar: with its help, from his office in the Winter Palace, Nicholas could communicate with officers in the General Staff located on the other side of the Palace Square. Soon, Jacobi's telegraph lines were extended into the tsar's country residences. Jacobi never left Russia. He became a Russian nobleman and died a venerable old man in St. Petersburg in 1874.

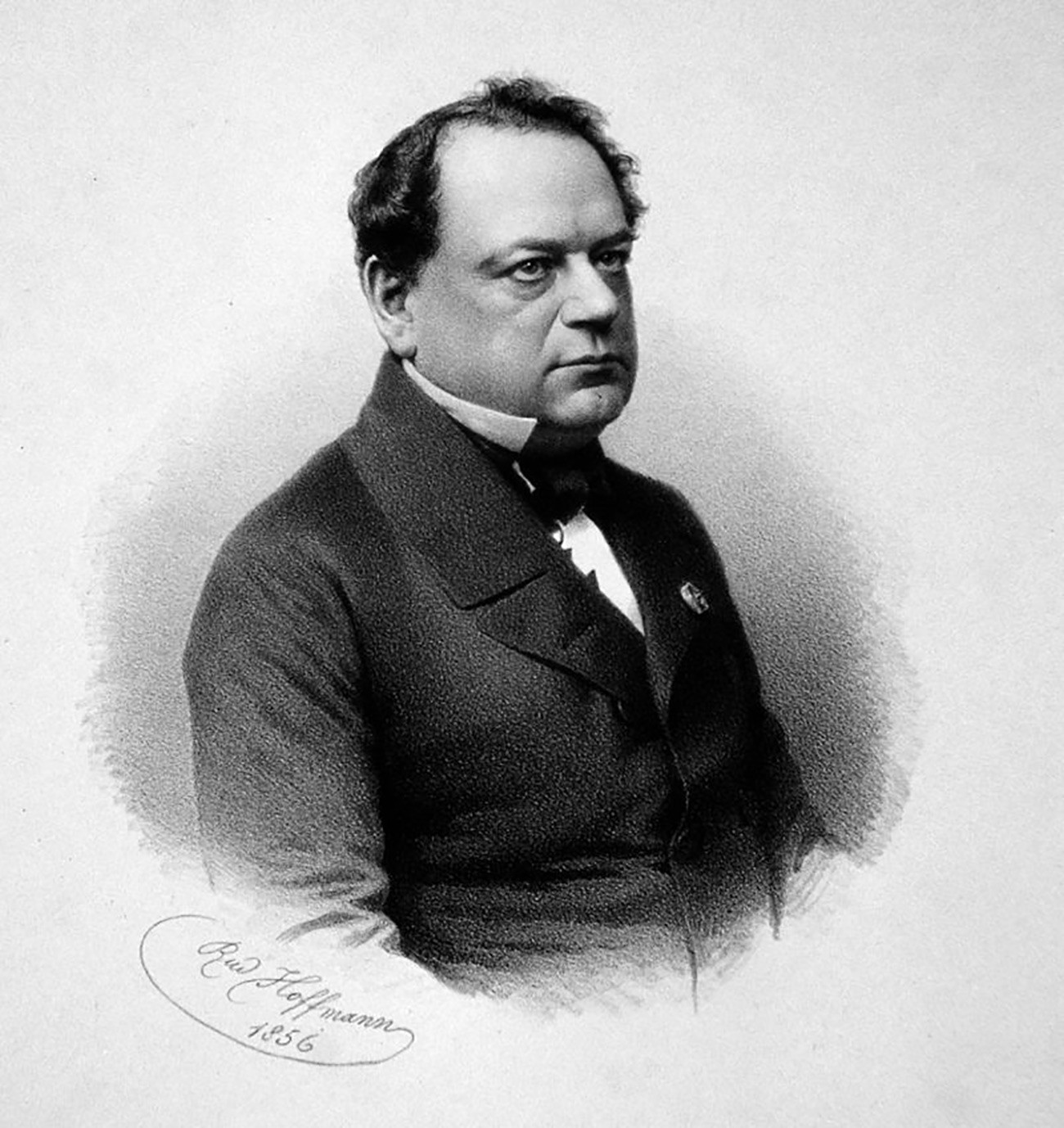

7. Marius Petipa (1818 – 1910), choreographer – France

Marius Petipa

Charles BergamascoToday, Russian ballet is one of the symbols of Russian culture. But it is worth remembering that one of its founders was a Frenchman. Marius Petipa was born in Marseilles. His father Jean-Antoine Petipa was a famous choreographer. The life of the whole family was dominated by dance and they were constantly on the move. From early childhood, Jean-Antoine's sons Lucien and Marius performed with their father. At the time, Russia was desperately looking for top-class choreographers.

The entire culture of the Russian elite was based on the ability to gracefully move and dance. That is why when Marius Petipa was invited to St. Petersburg in 1847, already four months later, he invited his father to join him: the Russian imperial capital was a Klondike for choreographers. Everybody wanted to train with the famous French dancers. In 1869, Marius Petipa was appointed the chief choreographer of the Imperial Theaters. In 1894, at the age of 72, he became a subject of the Russian Empire. Petipa lived a very long life and died in Gurzuf, in Crimea, in 1910. He is credited with having created classical Russian ballet and having trained several generations of outstanding dancers.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox