How did Russia treat its mentally ill before psychiatry?

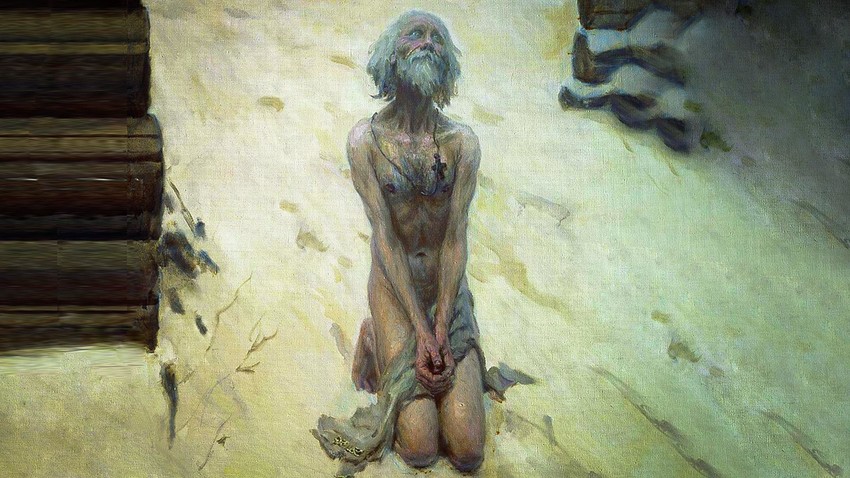

"St. Basil the Blessed. The Prayer" by Sergey Kirillov

Sergei KirillovSaint Basil’s Cathedral on Red Square, one of the most iconographic symbols of Russia, is actually named after such an individual. Saint Basil the Blessed (circa 1462-1469 – 1557) was considered one of the aforementioned holy fools – harmless, weak-minded individuals who lived off the charity of churches and monasteries. Up until the appearance of medical science in Russia in the late 18th century, the question of the insane was dealt with as in ancient times — everything was in the hands of God (or the gods, depending on how far back you go). Even many of the words in the Russian language to describe the mentally ill contained a reference to God (formed the same way as English words like “godless” and “godforsaken”).

READ MORE:Why did Russian tsars love ‘holy fools’?

Not all holy fools were simple madmen – especially given the social status accorded to some. On the death of St. Basil (who was highly esteemed for his asceticism and eschewal of material possessions), Ivan the Terrible himself was among the people who bore the coffin to its resting place. Among the holy fools, there were, of course, a few false prophets and swindlers who exploited the image for the sake of enrichment. And there were the genuinely deranged, who were said to be suffering from “black sickness.”

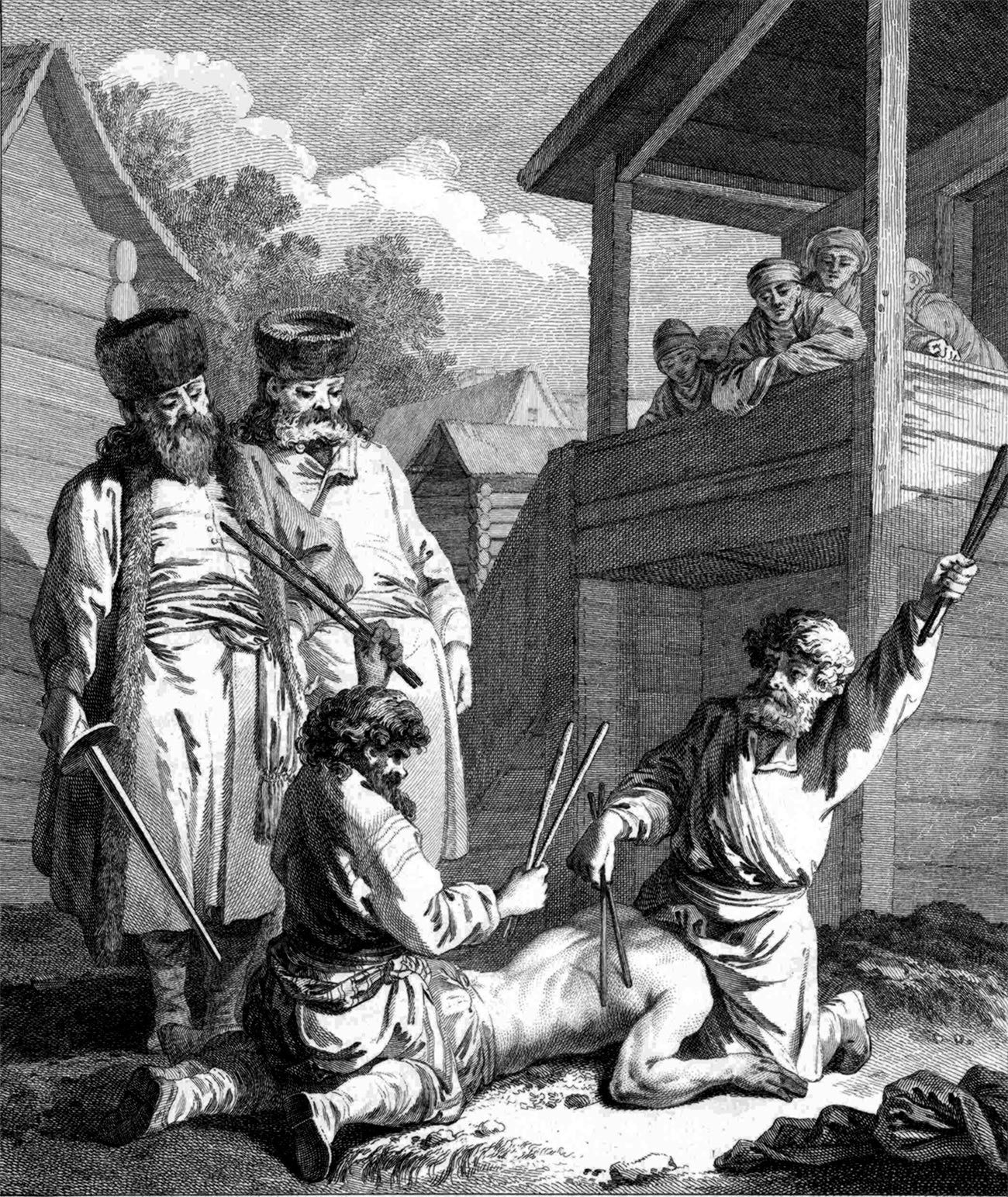

Exorcism. A European etching

Public domainIt was believed that such a state of mind was caused by a curse, the evil eye, or possession by demons. Mentally ill persons still physically capable were often engaged in agriculture, while the harmless and kindly were left to wallow in rural communities. Those believed to be possessed were often subjected to exorcism, which in Orthodoxy consisted in reciting prayers over the victim, sprinkling them with holy water, and anointing them with oil. As for the secular authorities, for a long time they declined to intervene in the treatment of the mentally ill.

The simpletons, the blessed, and the demoniac

Sergey Chaliapin and Andrey Plotnikov, modern scholars specializing in the history of the mentally ill in Russia, note that until the 18th century Russia had no laws covering the insane. In his book A History of Psychiatry (1928) Soviet psychiatrist Yury Kannabikh (1872-1939) wrote that the Stoglavy Sobor (Council of a Hundred Chapters) of 1551 (one of the main political and religious forums of medieval Russia) discussed the issue of confining the insane to monasteries. Yet this is a myth — the text of the Sobor’s resolutions (often dubbed Stoglav) contains no such matter. What the Stoglav did say (question 21, chapter 41 — in case you happen to have a copy on your shelf) is that “false prophets [...] who are naked and barefoot, whose hair has grown long and wild, who tremble and lament” must be driven out of society (without, however, any certain indication they should be jailed or punished). Naturally, many harmless simpletons were erroneously labeled as false prophets. In ancient and medieval Russia, they could indeed end up effectively imprisoned in monasteries or almshouses, alongside the poor and the wretched, or in cold pits and dungeons — in chains if they behaved aggressively.

But what if a rich and educated person went mad, and their insanity led to dangerous consequences? There were many such cases. In the 17th century, for instance, when the punishment for blasphemy and insulting the authorities could extend to execution, many tried to ascribe their words to a temporary loss of sanity. In 1640, an elder of Borschevsky Trinity Monastery (near Voronezh) by the name of Avraamyi wrote a denunciation of another elder, Seliverst. The denunciation turned out to be false. In his defense, Avraamyi claimed that he had acted due to an “aberration of the mind.” It didn’t work, however. Avraamyi was tortured and sent back to the monastery, his “temporary insanity” unrecognized.

Tsar Fedor Alexeyevich (1661-1682). His younger brother Ivan (1666-1696) was probably mentally disabled.

Public domainBut there was plenty of genuine madness to go around. In 1647, a sexton of a Moscow monastery was investigated for claiming to see and hear saints and angels. In 1631, in Moscow, a provincial peasant named Dorofei Ivanov was arrested for publicly insulting the tsar, but later released on bail and permitted to return home. The local governor’s order read as follows: “The man shall not be punished for he is simple and not in his right mind.” This shows that genuine insanity was at times recognized, and in the late 17th century it was written into the legislation.

In 1669, the term besnyi (“demoniac”) was introduced — such people were unable to act as witnesses and spared the death penalty for murder. That was followed, in 1676, by a decree from Tsar Fedor Alexeyevich that if people who were “deaf, blind, and dumb” decided to give away their estate, family members’ objections and claims would not be accepted — for “everyone is free to dispose of their estate as they see fit.” Presumably this law helped the Church to “persuade” many disabled and mentally ill people in the care of monasteries to hand over their land.

‘Whom the gods would destroy…’

"Meal of pilgrims in the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius," 1875, by Konstantin Makovsky (1839-1915). Mentally ill persons living in monasteries were often gathered for collective meals under supervision of the monks.

Konstantin MakovskyIn 1645, a resident of the town of Kashin, Dementy Lazarev, filed a complaint against his servant Mishka: “He is ruined in the mind, and has begun to slaughter animals and flog people. He went to the forest and villages, where he did all kinds of foul things to people and cattle.” When Mishka was chained up inside a hut, he “broke the chain, chewed the walls, and howled.” According to the surviving records of the subsequent interrogation, Mishka admitted to being sick with an “black sickness” (that is, mentally ill). Mishka was beaten with cudgels by employees of the Razrydny Prikaz (the war ministry of the 17th century) and returned to Dementy Lazarev. In general, however, in cases when a landlord or other citizen lost control over an insane individual, the secular or church authorities ordered that the madman be incarcerated in a monastery.

The abovementioned Dorofei Ivanov, who was sent home to his village, could not remain there, since he was apparently too ill in the head to be kept under control. He was taken to Kozheozersky Monastery under the wing of a kindly elder. There he was given small tasks commensurate to his capabilities.

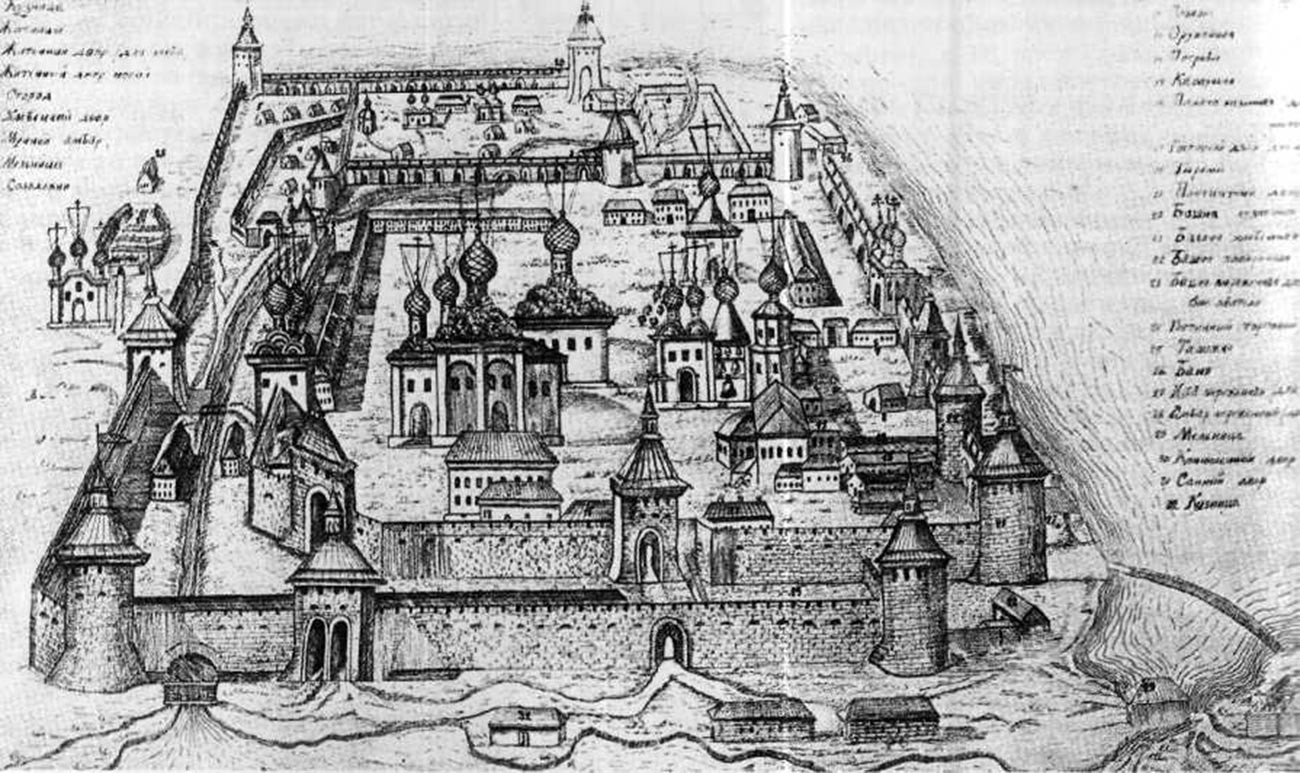

Beating with cudgels – heavy wooden sticks, a form of penalty in Tsarist Russia

Public domainPriests, boyars, and even abbots in the fog of drunkenness were sometimes imprisoned in monasteries as madmen. In 1695, Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery took in the (by then) former abbot (father superior) of Ferapontov Monastery, Filipp, who had lost his mind from drunkenness. His deranged behavior included beating his own brethren in the monastery, and during one winter journey he had “got off the sleigh, leaving the servants and horses, and wandered into the night-time forest, having thrown off his cassock.” The servants managed to catch the abbot and bring him back to the monastery.

In the monastery, afflicted individuals who were relatively responsible for their actions lived and worked with the monks; if they were overly simple-minded, they were used as farmhands; and if they were beyond all hope, they were kept in chains. Prayers, monastic rules, and labor were used as “medicines.” The high-ranking “feeble-minded” — especially those supported by wealthy relatives — were not forced to work, and some of them were even allowed to keep their own servants.

If the delirious (either from insanity or drink) recovered their senses, they (or their relatives, if any) wrote a petition to the church authorities confirming their sanity, and after an examination they could be released into society. Many, however, having regained their wits, remained at the same monastery, where they were accustomed to living.

The Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery, a place of exile and confinement for many mentally ill persons in ancient Russia.

Public domainThe number of mentally ill people in Russia rose in proportion to the growing population. In the second half of the 17th century, the people of Muscovy lurched from crisis to misfortune to disaster. Endless wars and crippling taxes brought the population to its knees. It was also a time of schism in the Orthodox Church — a moment of deep spiritual crisis for believers. If that were not enough, there was a plague epidemic in 1654-55, a solar eclipse in August 1654, the appearance of a giant comet in 1680... It was enough to make anyone howl at the moon.

READ MORE:Why Russia's Old Believers used to burn themselves alive

The reforms of the new tsar, Peter the Great, added further fuel to the fire. It was under Peter that monasteries finally began to refuse to accept the insane, in part because many were alcoholics or criminals feigning madness. But this is no longer the story of medieval Russia, but imperial Russia, when the mentally ill start to be treated medically, not just isolated from society.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox