5 things that were BANNED in Soviet schools

Those who grew up in the USSR know that the school was more than just an educational institution. The school system basically reared your kids - telling every Soviet child what to wear, how to look, how to write and - in the not so distant past - which hand to write with. Some children followed these norms like gospel, others hated the entire system with a passion, going to war with it every chance they got. Here are some of the most notable rules you were expected to observe in Soviet schools.

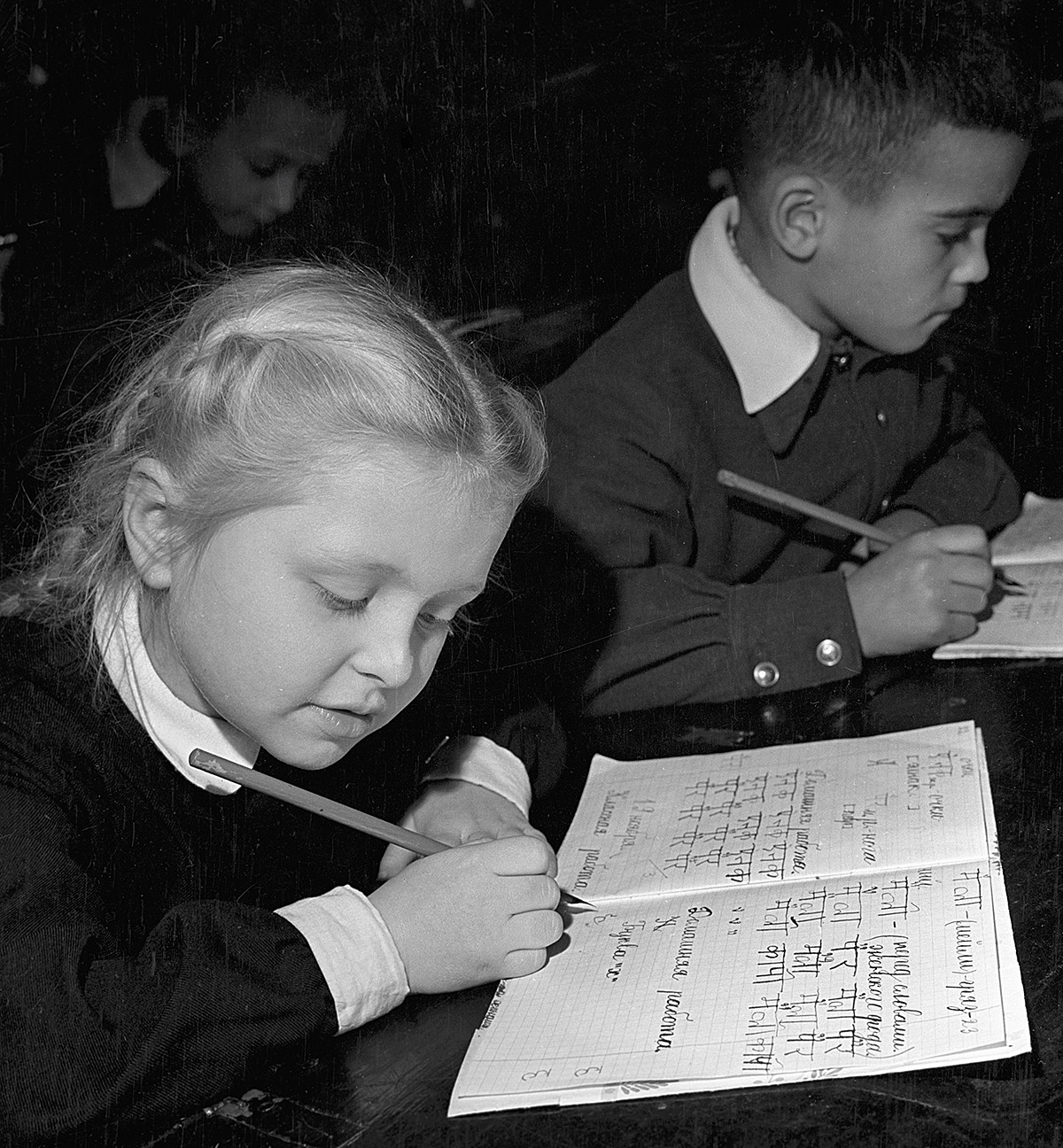

1) No left-handed writing

Officially, ‘lefties’ didn’t exist in the Soviet Union. Those that were unfortunate enough to be born left-handed, however, were simply retaught to write using their right hand. The idea was that it would be tougher for left-handed people to work and to go to war - guns and equipment were all made for right-handed people.

All the lefties had to obey, or to go to war with the teachers. “My dad is a lefty - he was retaught. He talked about being hit with a ruler for reverting to his old ways. When I started to write with my left, and the teachers threatened to retrain me, I told everyone to shove off. I’m still a lefty,” a ‘Pikabu’ social network user remembers. Another writes that “they couldn’t retrain me. Even tried giving me 2s (the equivalent of an ‘F’). I guess my stubborn nature simply won in the end”.

The practice was canceled only in 1985-86. The Ministry of Health confirmed that the practice of retraining was harmful to a person’s psychiatric health followed by the Ministry of Education accepting left-handed writing in schools.

2) No ballpoint pens

The Soviets believed that pens were the enemy of elegant writing, and therefore should be banned until the moment the child learned to write aesthetically in cursive. But, the measure was a temporary one and only applied very early on in a child’s education.

“I’m 48. In first grade, we were forced to write with quill pens, the type that had a wooden stock with a cartridge inside, where the quill went. There were ink bottles and blotting papers. You had to get a certain amount of 4s (Bs) and 5s (As) in writing class to be allowed to move up to an automatic quill pen,” Sergey remembers. “By second grade, we were allowed ballpoints, but only in blue.” [Red was the teacher’s color for correcting and grading, while black was used in the teacher’s journal to log the students’ progress].

Yuliya Karabintseva likewise remembers how, even in the 1980s, all the first-graders would use quill pens. “When the teacher saw a pretty writing style, we were allowed ballpoint pens.”

3) Only school uniform allowed

Jeans, sweaters, flower print dresses - and even even different-colored hair ribbons - were out of the question. Standardization was paramount.

“This doctrine against sticking out and showing one’s individuality would sometimes reach absurd heights,” Russia Beyond culture editor, Oleg Krasnov, says. “For instance, if anyone dared to show up in new sneakers, he or she would be scolded in front of the whole class, and possibly have their parents invited to see the principal. All students had to consider themselves equals.”

Clothing items like sneakers were a rare sight in the USSR, with only a handful of children having access to any, due to their parents’ work trips or other kinds of special permits to travel abroad. The rest of the country had to contend with Soviet-made shoes that all looked quite similar. “My mother used to visit socialist bloc countries and bring me clothes. It was always a pleasant treat, but I tried to never wear anything like that to school,” Oleg adds.

4) No nail polish, makeup or dyed hair

You could be thrown out of class for any of these, as well as publicly humiliated. Boys with long hair, for example, were considered hippies. Today, the teacher would be taken to trial; back in the day, it was you who was the outcast, and good on them for “teaching you a fun little lesson”.

One school teacher even had this to say: “You’re really lucky to be living in modern times. My father had had his hair cut three separate times by the principal, personally. She would simply cut a huge wad of hair right there in front of the morning lineup.”

“I always had puffy black eyelashes and slightly slanting eyes,” Yuliya Shikhovtseva recalls. “But in senior grades, it started to attract increased attention from the teachers, who thought that I was using makeup. If you only knew how many times I was thrown out of class to go to the bathroom and wash off the non-existent eyeliner.”

The same went for nail polish, but some children went against the rule on principle. “My deskmate, Nina, would paint the nails on one hand and hide them in a fist whenever the teacher would approach. I don’t know what the point of all that was, perhaps, just a protest gesture,” Yiliya adds.

5) No earrings

Now we come to the most tried and tested way to infuriate your Soviet teacher - and that was wearing earrings, or having any other type of piercing. Only the most modest type of clove-shaped earrings were permissible sometimes. Everything else elicited a colorful reaction from the teaching body.

“In around 1989, at the dawn of the Perestroika, while the musical underground had already spread far and wide, there were school students who considered themselves metalheads and punk-rockers. I had a punk in my class,” Krasnov remembers. “He looked pretty ordinary at school, the only giveaway was the slightly longer hairdo, made to look unkempt. But one day, he showed up with a crucifix earring. It was history class - the kind of history that was taught from the communist point of view. The teacher was deep into another story when her eyes suddenly fixed on him. She saw the cross and began to stutter, before slowly sitting down in her chair and visibly trying not to lose consciousness. It wasn’t long before she came to, and began yelling at him to take out the earring. The guy calmly refused. The teacher went red in the face and threw him out.”

What about now?

There’s hardly anything in common between current schools and the Soviet ideology of forced equalization of yesteryear. Nonetheless, some of the old bans have survived to this day. But the situation is different from school to school. Some schools demand strict adherence to the uniform rule, others prohibit the use of mobile phones and the wearing of long hair.

“Boys in our school weren’t allowed long hair as well, and the girls weren’t allowed makeup. In 9th grade I was ejected from class for deciding to become a blonde. No jeans or sneakers either. I graduated school in 2012,” writes Ketto.

More often than not, the more elite the school, the stricter the rules: “In a relatively ‘tough’ Moscow school (with paid tuition), everything gets the axe even to this day, aside from ballpoint pens. And for kids to get an appreciation for the reality of life, they’re also not allowed to print out their homework until seventh grade… you only write by hand. Not a far cry from the Soviet Union, I should say. Except now, you dish out 100,000 rubles (approx. $1,400) annually.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox