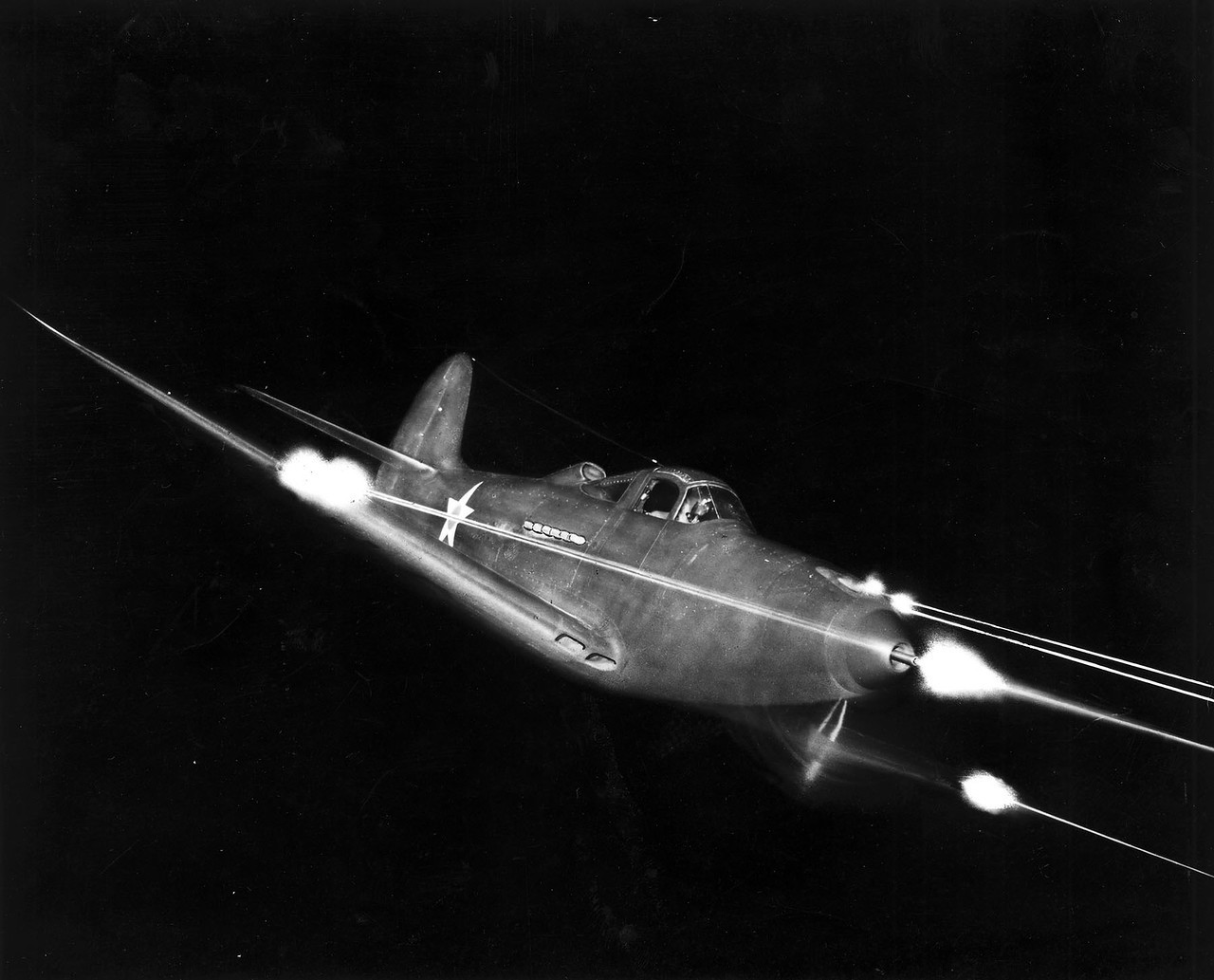

Why did Soviet aces adore this U.S. fighter?

American pilots were not keen on the Bell P-39 Airacobra. The fighter handled poorly at high altitude, where it had to escort the heavy B-17 Flying Fortress on bombing missions, and where the main air battles with the Luftwaffe on the Western Front took place. Not being sentimentally attached to the plane, the Western allies supplied it in large quantities to the USSR under the Lend-Lease program. In total, the Soviet Air Force received almost 5,000 such aircraft — more than half the total number produced.

The Soviet attitude to the P-39 was radically different. In air battles on the Eastern Front, typically at low and medium altitude, it was indispensable. The unusual design, with the engine located behind the cockpit, gave the aircraft excellent speed, maneuverability, aerodynamics, and visibility. True, this also made it unstable and difficult to control, so that any mistake could lead to a stall. The Airacobra was not an aircraft for novices, only for experienced pilots, which perhaps added to its appeal.

Soviet pilots raved about the fighter’s 37-mm cannon (20 mm on early models). “The shells are very powerful. One hit, and that was usually goodbye to the enemy…” recalled pilot Nikolai Golodnikov: “And we attacked not only fighters. Bombers, watercraft, you name it. For such targets, 37 mm was very effective.”

But the reaction to the P-39’s four mounted 7.7-mm Browning machine guns was more restrained. They were generally considered incapable of shooting down an enemy plane, only damaging it. Soviet mechanics often didn’t hesitate to remove two of them to reduce the weight of the fighter and improve maneuverability.

The Airacobra coped well with landing and taxiing on soggy or snow-covered airfields. Whereas in the Western and Pacific theaters this was largely irrelevant, in the USSR, with its far harsher climate, it was a major plus. On the downside, the Allison V-1710 engine did not like the Russian cold, often cutting out as a result. The situation improved after Bell Aircraft Corporation upgraded them on the recommendations of Soviet specialists.

A separate problem was the plane’s car-type door. Pilots could comfortably board the plane on the ground, but during an emergency bailout in the air, they risked smacking into the tail. This meant that Soviet pilots tried to remain inside their damaged aircraft as long as possible in an attempt to reach the landing strip. Fortunately, the P-39 had exceptional survivability: often planes with more bullet holes than metal in the fuselage returned safely from a dogfight.

Airacobras fought across the entire length of the Soviet-German front: from the Arctic to the Caucasus. They played a significant role in the Soviet Air Force’s first major victory over the Luftwaffe — in the air battles over Kuban in April-June 1943. More than 2,000 aircraft participated in the battles on both sides.

On Sept. 9, 1942, in Murmansk Region, Guards Lieutenant Efim Krivosheev performed the first ever air ram by an Airacobra. Having used up all his ammunition, he spotted a Messerschmitt on the tail of his commander, Pavel Kutakhov. Without thinking twice, he rammed the enemy fighter, saving Kutakhov’s life at the expense of his own.

The hard-to-handle but effective P-39 was designed for the best of the best, and served mainly in the guards units. Alexander Pokryshkin, Grigory Rechkalov, Alexander Klubov, Nikolai Gulaev, the brothers Dmitry and Boris Glinka, and other top Soviet aces all flew the American fighter. Pokryshkin, the second highest-scoring of all Allied fighter pilots, made 48 of his 59 kills with it, and Rechkalov 50 of 56. Even when faster and more maneuverable aircraft began to enter service with the Soviet Air Force toward the end of the war, many Soviet pilots remained faithful to their beloved Airacobra, which never let them down.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox