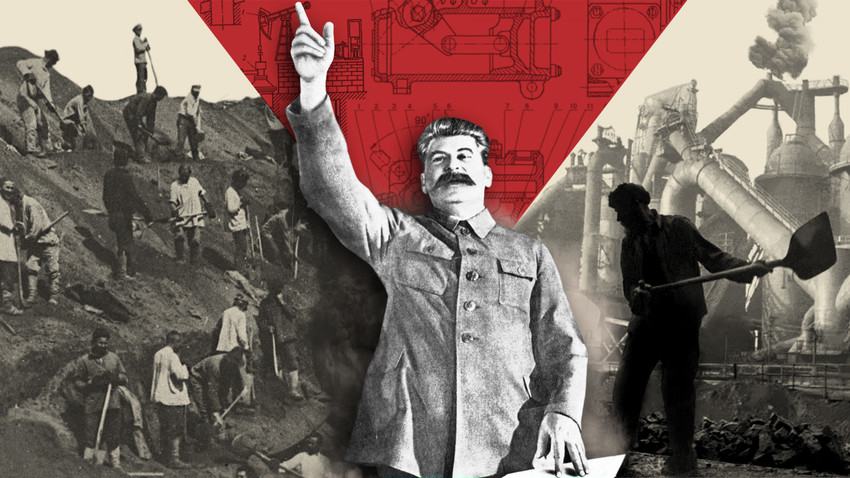

“Factory workers, both men and women, who wanted to find a place to live in and around towns like Stalingrad, Magnitogorsk, Novokuznetsk, had to live in earth shelters they dug out in the neighboring hills. If people could live and do useful work in such living conditions and during enormous shortages of food and goods of first demand, this could only be explained by the fact that the Russians aren’t used to anything but suffering and hardship.”

That’s what German diplomat Gustav Hilger wrote about the times of industrialization in the USSR, the times when the first five-year plans were implemented. Indeed, the transfer of the USSR from an agricultural to industrial power was done at the cost of the lives and the living conditions of the Russian people.

A house made of soil in Magnitogorsk, 1929

SputnikDuring the Civil War in Russia and after it ended, the Bolshevik state initiated a massive onslaught on the wealthy peasantry to confiscate and re-distribute food and goods they produced and nationalize their property.

In 1925, the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist party declared the beginning of the transformation of the USSR from an agricultural to industrial power and issued an order to create the first five-year plan (1928-1932).

By 1927, the plan was finalized. This marked the beginning of the planned economy – to put it simply, the USSR government defined certain key product indicators in the country’s economy to be met in 5 years. Industrial production was expected to grow by 136 percent over five years, labor productivity was to be increased by 110 percent, 1,200 new factories were to be built.

But the government didn’t take into account the cost of the industrialization drive – it just defined what had to be done, and if it wasn’t done, then repressive measures would be taken against all responsible persons. Eventually, simple workers had sometimes to do the impossible, which was quite appropriately reflected in the famous motto of the era, “The five-year plan in four years!”

"Five-year plan in four years – will do!"

Public DomainBecause of the collectivization of peasant property, vast numbers of former peasants flocked to the cities, increasing urbanization. Between 1928-1932 the urban labor force increased by 12.5 million people, of which 8.5 million were from villages.

Meanwhile, in the villages, there was sometimes simply nothing to eat and nowhere to work. This resulted in the horrible famine of the beginning of the 1930s in the USSR – but industrial production indeed grew. However, this was largely done with the help of foreign countries.

According to the leadership of the Communist Party of the USSR, there was a high probability of a war with capitalist states, which required thorough rearmament. But at the beginning of industrialization, the USSR didn’t have the necessary equipment – they simply needed factory machines to produce factory machines. So the equipment was purchased from the same ‘capitalist states’ of Europe and the USA.

In 1929-1932, U.S. construction firm “Albert Kahn Inc.” built over 500 plants and factories in the USSR: tractor factories in Stalingrad, Chelyabinsk, Kharkov, auto plants in Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod, factories in Stalingrad and Sverdlovsk, steel mills in Kuznetsk, Magnitogorsk, Nizhny Tagil, etc.

A worker at the Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works, 1937

Vladislav Mikosha/SputnikIn 1931 the USSR placed orders in Germany for the sum of 919 million Deutschmarks – the USSR bought half of all Germany’s exported iron, 70 percent of German metalworking machines, 90 percent of their steam, and gas turbines and steam-forging and pressing machines.

Importantly, foreign engineers and specialists were invited to the USSR to work and teach Russians. Advertisements such as this were placed in the U.S. press: “Intellectuals, social workers, men and women who have a specialty are sincerely invited to Russia... the country where the world's greatest experiment is being conducted…”

READ MORE: How the newborn Soviet state took capitalist help and hushed it up

Obviously, the foreigners wanted to know what working and living conditions were like. A German ‘informational group,’ organized with the help of the USSR’s Foreign Affairs, visited Saratov, Stalingrad, North Caucasus, Crimea, Magnitogorsk, Chelyabinsk, and other cities. They found no abandoned equipment. They only saw young Soviet technicians showing amazing skills and ingenuity – and at the same time, the factory machines were being used with such intensity that they wore out 10-15 times faster than in the USA and Europe – the machines were constantly in use.

The same could be said about people. In 1936, William C. Bullitt, the US’s first ambassador to the USSR, wrote: “The standard of living in the Soviet Union is extraordinarily low, lower perhaps than that of any European country, including the Balkans. Nevertheless, the townsfolk of the Soviet Union have today a sense of well-being. They have suffered so horribly since 1914 from war, revolution, civil war, and famine, that to have enough bread to eat, as they have today, seems almost a miracle.” But did they really have enough bread to eat?

Russians in a line to a department store. Moscow 1931

Public DomainIf the machines ran non-stop, what about the Soviet workers? Well, in those times, there was little time for rest. In 1929-1931, the Soviet calendar was changed for the needs of the five-year plans – instead of a 7 day week, 5 day weeks were introduced. Workers had to work 4 days with one day off – but it wasn’t the same day for everyone, people worked in shifts so that the machines wouldn’t stand idle even for a day. This meant decreasing the overall annual days off for everyone by 42 percent.

What about the food? The USSR got the money for its industrial revolution by exporting crops and grain, which drained food from the whole country. In 1928, all grain stocks that were seized from the peasants, farm products, and other goods were sent abroad. In 1928, the export amounted to 7.4 million rubles. In 1929, it was 3 times more — 23 million rubles. A ninefold jump in 1930 – 207 million rubles.

Obviously, inside the USSR, this resulted in monstrous shortages. Even for foreign workers. “Nothing but soap. They should hang the bosses [of the plant] on the first tree. Queues for lunch…” – an American worker in Nizhny Novgorod wrote in the 1930s. “For two months, we don't get any fat, not even milk. We can't buy on the market. If the food doesn't improve, we'll have to leave,” another contemporary foreigner wrote. By 1934-1935, most of the foreigners, having shared their valuable production experiences, had to leave. What was left for the Russians?

READ MORE: The 1930s USSR through the eyes of 3 Americans

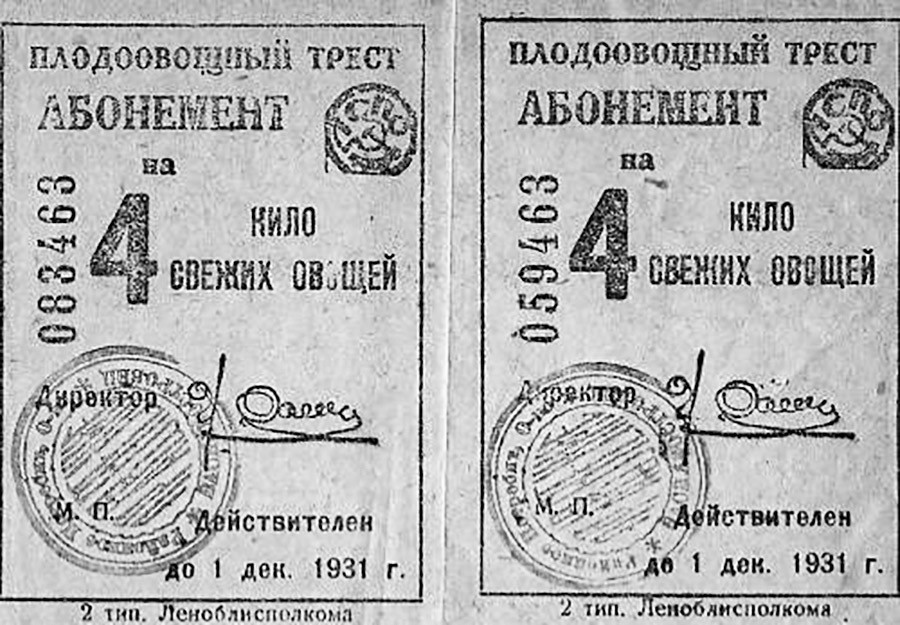

Ration stamps for 4 kg of fresh vegetables, 1931

Public DomainBy the end of the 1920s, in cities, food began to be rationed via food stamps. Not everyone got the necessary rations. State security reported to Stalin what workers were saying: “This fish is rotten like the whole five-year plan is. If it gets worse and worse every day now, then nothing good can be expected in the future. The workers are now so humiliated that they are fed worse than cattle. Delayed earnings, there is no money.” Not only food, but commodities like clothing and hygiene products were hard to obtain through the 1930s.

Living conditions for the workers were also poor. In big cities, most people were living in overcrowded communal apartments or, even worse, in barracks and wooden huts – even in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Two-storeyed barracks in Moscow, 1930s

Public DomainIt’s really hard to assess the real results of the five-year plans because the numbers provided by the USSR’s economists are very often questionable. Still, here’s what we have. Compared to 1928, by 1937, the Soviet production of iron grew 439%. Steel – 412%. Coal – 361%. Production of metal cutting machines – 2,425%. 80% of all production was done in factories built during the 1st and 2nd five-year plans. Over 4,500 new industries were started in the USSR during that time. The overall workforce productivity increased by 90 percent.

The third five-year plan, planned for 1938-1942, was disrupted by the beginning of WWII: even in 1939, the state had to sharply increase spending on the military industry; by 1940 it grew to about 33% of the budget, by 1941 – to 43%. The war broke out then, so there wasn’t much time for planning.

Joseph Stalin in 1949

SputnikThe fourth five-year plan rolled out in 1946. Stalin demanded the USSR to annually produce “up to 50 million tons of iron, up to 60 million tons of steel, up to 500 million tons of coal, up to 60 million tons of oil…” In reality, in 1946, only 10 million tons of iron was cast, 13.3 million tons of steel was produced, 21.7 million tons of oil extracted… The country couldn’t just immediately recuperate and become more efficient after a devastating war. Actually, Stalin’s unrealistic demands were met only after 15 years in 1961.

The planned economy, history showed, proved to be a giant hoax. Soviet economists, accountants, politicians often simply falsified the numbers of production to fit the necessary demands or recalibrated the plans: for example, the sixth five-year plan (1956-1960) was replaced by a “seven-year plan,” and so on. In total, there were 13 five-year plans in the history of the USSR - the last of them introduced in 1989. But since post-war times, all this planning was only implemented on paper – the country and its people lived in reality, often a harsh and tormented one, but not the reality created in government offices.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox