5 illnesses of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin in 1930

Sputnik“The lifestyle is extremely unhealthy, sedentary. Never goes in for sports or any physical work. Smokes (pipe), drinks (wine, prefers Kakheti [local Georgian wine]). During the second half of his reign, he spends every evening at the table, eating and drinking in the company of the members of his Politburo. How, with this lifestyle, he lived to be 73 years old is amazing,” Boris Bazhanov, Stalin’s secretary, recalled. Indeed, during his life, Stalin had many conditions and diseases, exacerbated by a harsh work schedule and constant stress.

1. Myasthenia (weakness of the left arm)

A group of Soviet leaders in the Kremlin. Left to right: Georgi Malenkov, Lazar Kaganovich, Joseph Stalin, Mikhail Kalinin, V.M. Molotov, and Kliment Voroshilov.

Getty ImagesThe official version went that at 6 years of age, Stalin was hit by a horse phaeton carriage, injuring his left arm and leg. “Atrophy of the shoulder and elbow joints of the left hand, due to bruising at the age of six, with subsequent suppuration in the elbow joint,” his clinical record stated. However, there are photos where Stalin can be seen controlling his left hand quite well – lifting his daughter, for example.

On the other hand (pun unintended), his left arm often remained motionless while he was walking, arm half-bent, pressed against the body. It also seemed shorter than the right one.

There is a hypothesis that the reason for Stalin’s “lame left hand” was Myasthenia gravis, a long-term neuromuscular disease that leads to varying degrees of skeletal muscle weakness. Myasthenia gravis can be both congenital and acquired and usually starts in people at 20-40 years of age.

2. Rheumatoid arthritis

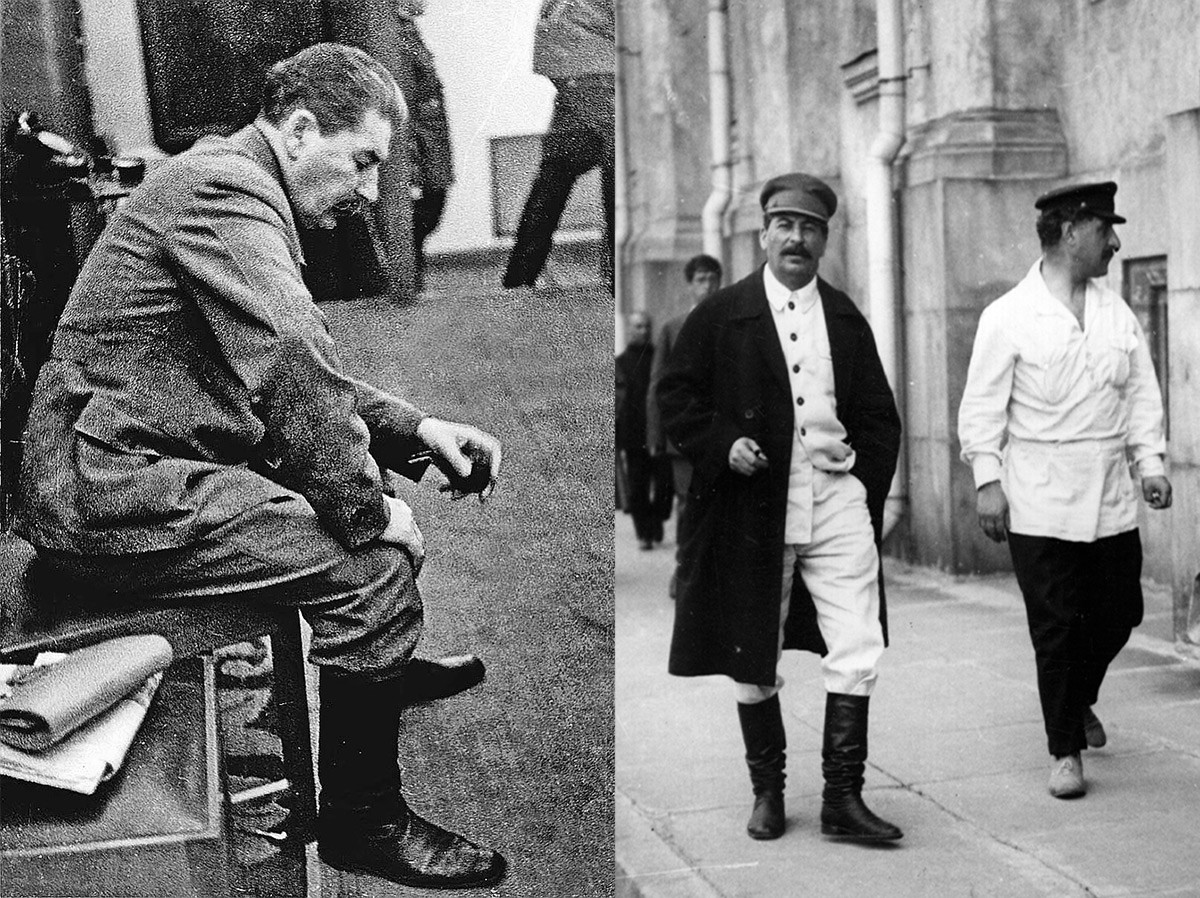

Stalin and his boots

Getty ImagesFor years, Stalin suffered pains in his legs; in later years, he was often seen slightly limping. Some attribute this fact to his webbed toes – the 2nd and the 3rd fingers on Stalin’s left foot were fused together. Although not a disease, but a malformation, syndactyly wasn’t the reason for Stalin’s limping.

It was rheumatoid arthritis – Stalin suffered inflammation (and probably even deformation) in the joints of his both legs. He had to wear specially crafted military boots made of super soft leather, the so-called “boots with holes” – apparently, the boots were so comfy that Stalin rarely took them off, stomping holes in their soles. When he was motionless, rheumatoid pains would worsen, so during long meetings, he could not sit in one place and would walk around the office.

From 1925-1926 (47-48 years of age), Stalin went to resorts to take warm hydrogen sulfide baths from natural sources for his legs. But rheumatoid arthritis is a complex disease that may affect other parts of the body – it can cause inflammation of the lungs and low red blood cell count, among other consequences.

“In Nalchik, I was close to pneumonia. I have a ‘wheeze’ in both lungs and I’m still coughing,” Stalin wrote from his 1929 resort trip to his wife. In 1935, doctors forbade Stalin to swim in the sea – because of his rheumatoid arthritis.

3. Smallpox

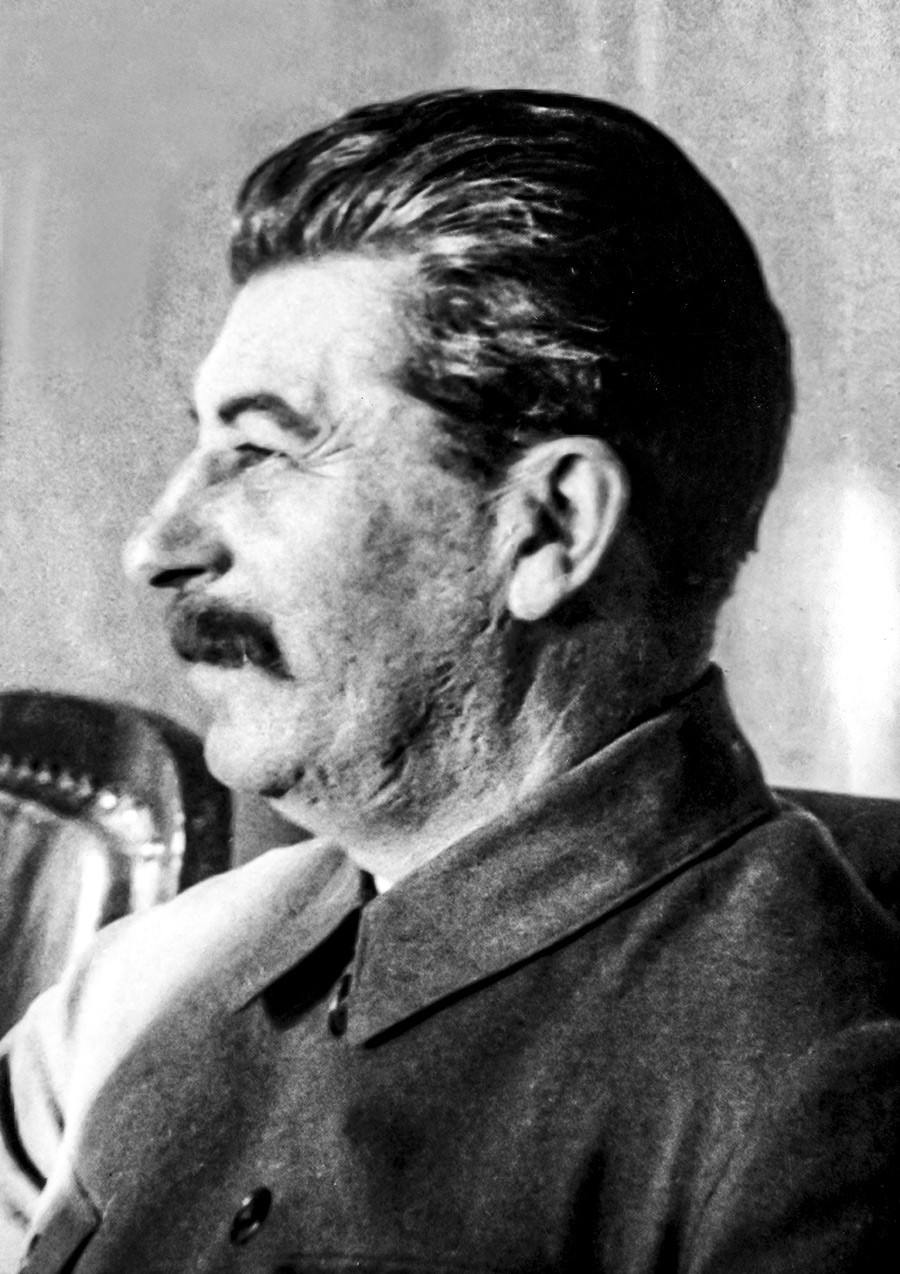

Stalin around 1932. Photographer: James E. Abbe

Getty ImagesStalin probably contracted smallpox as a 5-year-old boy in Gori, Georgia. The disease left his face slightly pockmarked – a physical handicap Stalin considered disgusting. During Stalin’s criminal activity in his youth, the police’s profiles on him always contained the information on his smallpox marks as an important feature of the suspect. Later, in Stalin’s photos that would appear in the Soviet newspapers, pockmarks on his face were removed by retouchers.

4. Appendicitis

Stalin with his friends and his wife Nadezhda Allilueva (R)

SputnikIn 1921, Stalin suffered an inflammation of the appendix. By that time, he was already a high-ranked official in a new country, so he was consulted by one of Russia’s most experienced surgeons, Vladimir Rozanov. It was the same surgeon who extracted the bullet from Vladimir Lenin in 1922, 4 years after an attempt on Lenin’s life in 1918. So among the leaders, Rozanov was already trusted.

“The operation was very difficult,” Vladimir Rozanov recalled. “In addition to removing the appendix, I had to do a wide resection of the cecum and it was difficult to vouch for the outcome.” Most of the operation was performed under local anesthesia, but as it became more complicated, Rozanov had to put Stalin under chloroform anesthesia – a very dangerous form of general anesthesia that could potentially make the heart stop. But Stalin recovered.

5. Atherosclerosis of the brain vessels

Stalin always worked a lot, especially during WWII. He took part in endless meetings with his officials and commanders – 5-7 a day, that lasted up to 10-12 hours in total. The meetings were held at any time of the day or night, usually in the Kremlin or at Stalin’s dacha in Kuntsevo (close to Moscow). The chiefs of the General Staff met with Stalin almost daily and sometimes several times a day.

Vladimir Vinogradov, who was Stalin’s attending physician in the 1940s, found insomnia and arterial hypertension to be the leader’s most acute problems. After returning from the Potsdam Conference (July 17 to August 2, 1945), where stressful post-war negotiations took place, Stalin’s condition worsened. He complained of headaches, dizziness and nausea. There was an episode of severe pain in the heart area and a feeling that the chest was being “tightened with an iron band”, which was most likely due to a small-scale heart attack. But Stalin wouldn’t agree to upkeep any rest schedule.

Between 10 and 15 October 1945, Stalin suffered a stroke. However, the stroke did not lead to a brain hemorrhage and there was only a blockage of a small brain vessel. But for two months after that, he refused to talk to anybody from his inner circle, not even on the telephone, while spending time at his dacha.

From 1946, Stalin eased up his schedule. His meetings would only take up to 2-3 hours, not more, and he mostly stayed at his Kuntsevo Dacha, not in the Kremlin. “In the summer, he spent all day moving around his garden – servants took his work documents, newspapers and tea to the garden for him. In those years, he wanted to be more healthy, wanted to live longer,” Stalin’s daughter Svetlana once recalled.

Hypertension, dizziness, breathing problems – all are symptoms of atherosclerosis, a condition when the inside of an artery narrows, due to the buildup of atheromatous plaque. Therapist Alexander Myasnikov, Stalin’s attending physician in the last years of his life, was present during Stalin’s autopsy, reported “severe sclerosis of the cerebral arteries”. This illness made Stalin’s final years excruciating.

Stalin in 1952

Getty ImagesIn October 1949, a second stroke happened, followed by partial loss of speech. Stalin began to take long work leaves – from August to December 1950, then from August 1951 to February 1952. He started developing cognitive and memory problems. Nikita Khrushchev recalled that sometimes Stalin could forget the name of a person he had been in contact with for decades. “I remember once he turned to Bulganin (Vladimir Bulganin, Politburo member) and could not remember his last name. He looked at him protractedly and said: ‘What’s your last name?’ – ‘Bulganin!’ – Vladimir answered promptly. Such situations were repeated often and it drove Stalin into a frenzy,” Nikita Khrushchev wrote.

Although in his final years, Stalin removed himself from all work, his condition didn’t get better. By late 1952, he frequently experienced blackouts and could no longer go up the stairs without assistance. Pavel Sudoplatov, a Soviet intelligence general, recalls his last meeting with Stalin at his dacha in February 1953: “I saw a tired old man. His hair had thinned considerably and, although he always spoke slowly, now he pronounced the words with an effort and the gaps between words became longer. Apparently, the rumors about two strokes were true.” Stalin died at his Kuntsevo dacha on March 5, 1953. The official cause of death was determined as intracerebral hemorrhage.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox