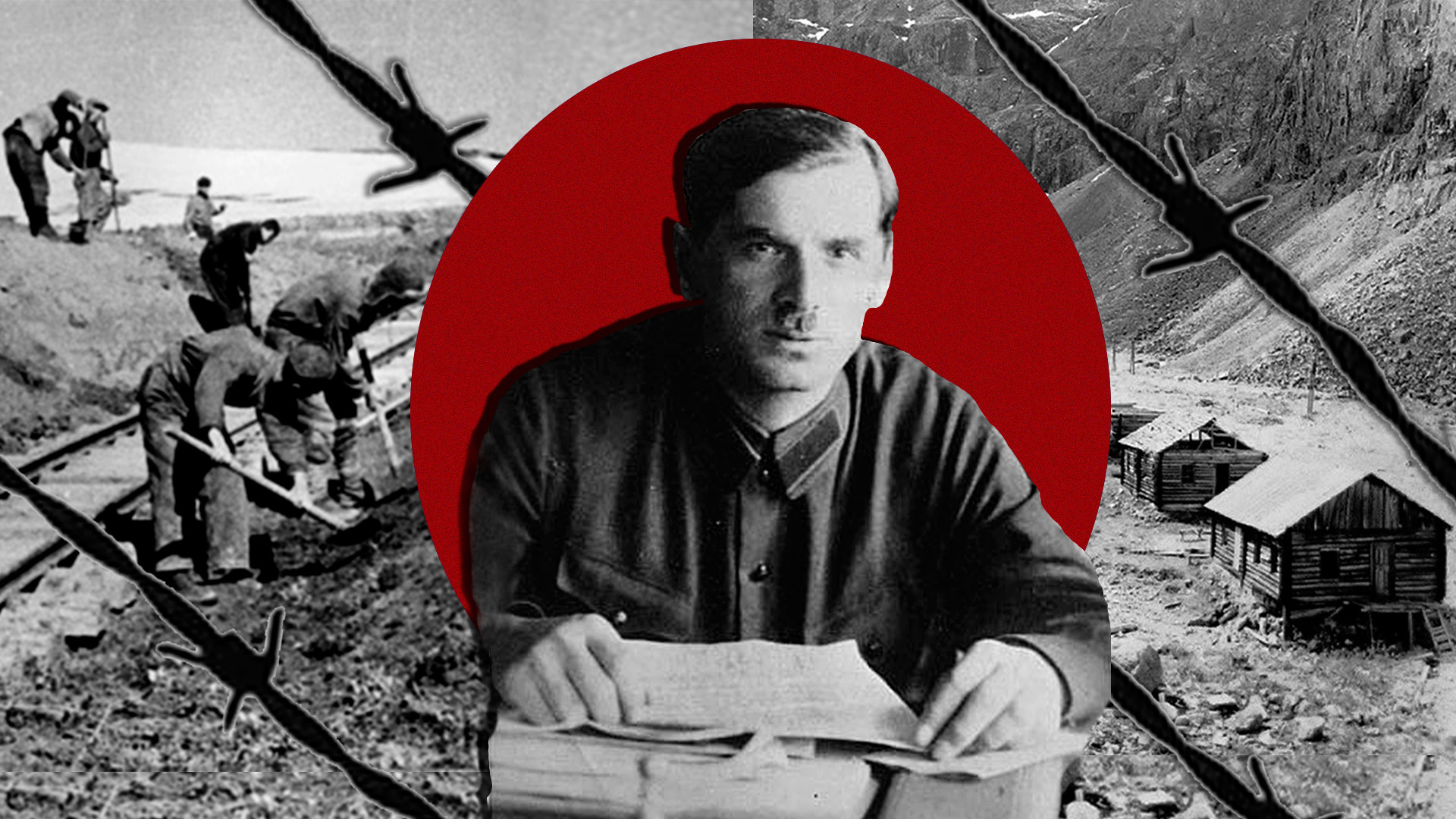

How a GULAG prisoner ended up as its boss

The "tireless demon” of the "Archipelago" (as the Gulag was known), is how Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the main chronicler of the Soviet system of forced labor camps, described Naftaly Frenkel. The publication of Solzhenitsyn's book The Gulag Archipelago made Frenkel widely known: the author names him as the person behind the idea of using mass prisoner labor in the USSR. "It would seem that there had been camps even before Frenkel, but they had not taken on that final and unified form which savors of perfection," Solzhenitsyn wrote with bitter irony.

From millionaire to prisoner

The life of Naftaly Frenkel is a real success story. Fortune followed him wherever he went, even to places of detention. Frenkel was born in 1883, in southern Russia. In general, Jews in tsarist Russia had a hard time - they were deprived of many rights and could only work as small-time traders or in artisan enterprises. However, Frenkel was lucky to find himself in Odessa, a city where a third of the population was Jewish and Jews had many more opportunities.

Odessa in the 1920s

Volsky "Odessa. History of the hero city" / Odessa region publications,1957Naftaly learned about the construction business, worked as a foreman and later became a very successful timber merchant. Then, during the years of World War I, he made a fortune from arms sales, but his plans for the future and possible further success were interrupted by the 1917 Revolution. By now a notable businessman, Frenkel, was forced to transfer his money abroad so as not to lose it all, and for a while he hid in Turkey.

But in the 1920s the New Economic Policy was introduced in the USSR: The country was in severe economic decline, so the Bolsheviks softened the policy of War Communism and brought back small businesses. Frenkel returned to Odessa and got involved in trade and smuggling. In their memoirs, some of his contemporaries have suggested that Frenkel quite possibly collaborated with the local special services by carrying out currency exchange transactions for them or providing information about crime rings.

But Frenkel's successful back-street dealing came to the attention of the authorities in Moscow. In 1924 he was sentenced to death, subsequently commuted to 10 years’ hard labor in the Solovki prison camp on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea.

Prison camps before Frenkel

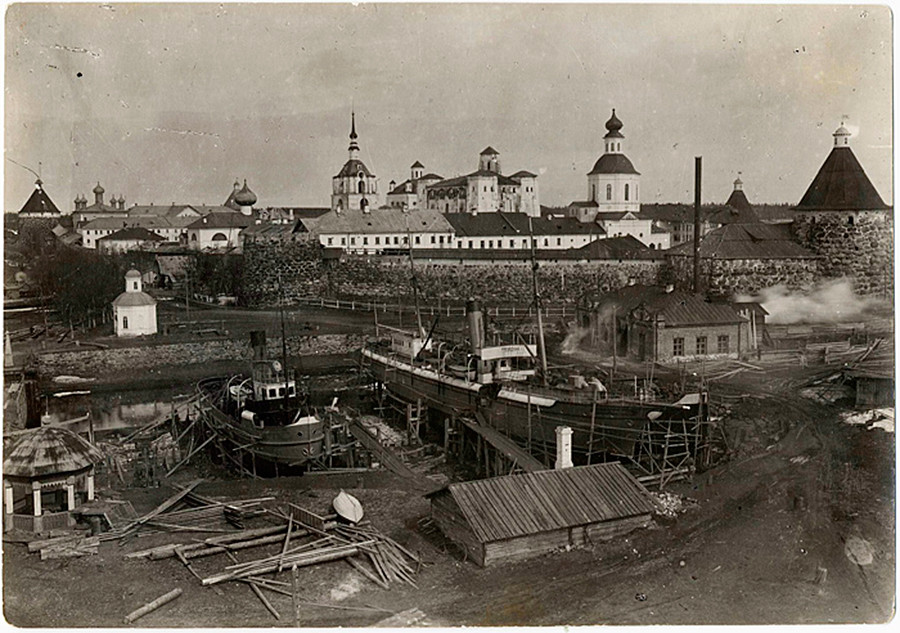

Solovki prison camp in the former Solovetsky monastery

Solovki.caIn the 1920s the USSR already had a system of prison camps, but it was still far from being the mass punitive-correctional Leviathan that it was to become in the mid-1930s. The conditions in which inmates were kept were not yet all that severe, prisoners didn't starve that much and they weren't worn down by relentless back breaking work, as became the case later.

The Solovetsky prison camp was one of the first to be set up. A monastery conveniently located on an island in the north of Russia was a "perfect" place of banishment and detention. The prisoners lived in former monastic cells and church buildings.

"Finding himself in a trap, he evidently decided to make a business analysis of this life too," Solzhenitsyn says about Frenkel. In the first months of his detention Frenkel had already come up with the initiative of setting up artisan workshops to make the camp profit making.

Solovki prisoners working with leather

Solovetsky museumThe management approved the initiative and the Solovki prisoners began to make clothes and shoes that were then supplied to shops in Moscow. By the way, among the raw material they used was leather found in the monastery's store rooms. In 1927 the enterprising prisoner was granted early release and appointed head of the camp's production department!

Frenkel transforms the camps

Gulag chiefs, Naftaly Frenkel on the right

Public domainFrenkel had bigger plans - in 1929 he submitted a project to Moscow proposing the use of mass prisoner labor to build roads, dams and other infrastructure projects. The Soviet authorities, who were embarking on their policy of industrialization, liked the plan so much that Frenkel was asked to head the entire production process of the Gulag system.

It was Frenkel who turned the camps from places of detention into "corrective labor" colonies. Under his management, the prisoners, who constituted a free labor force, were involved in the USSR’s most ambitious construction projects. It was essentially slave labor.

Prisoners build a railway in Siberia

Taymyr ethnography museumNew Gulag outposts were opened across the country for Frenkel’s projects, to which more and more prisoners were sent. "And it wasn't clear at all whether the prisoners built them because they were in prison or whether they were in prison so that they could build them," prominent journalist Leonid Parfyonov says in his documentary film Russian Jews.

White Sea-Baltic Canal and Baikal-Amur Railway

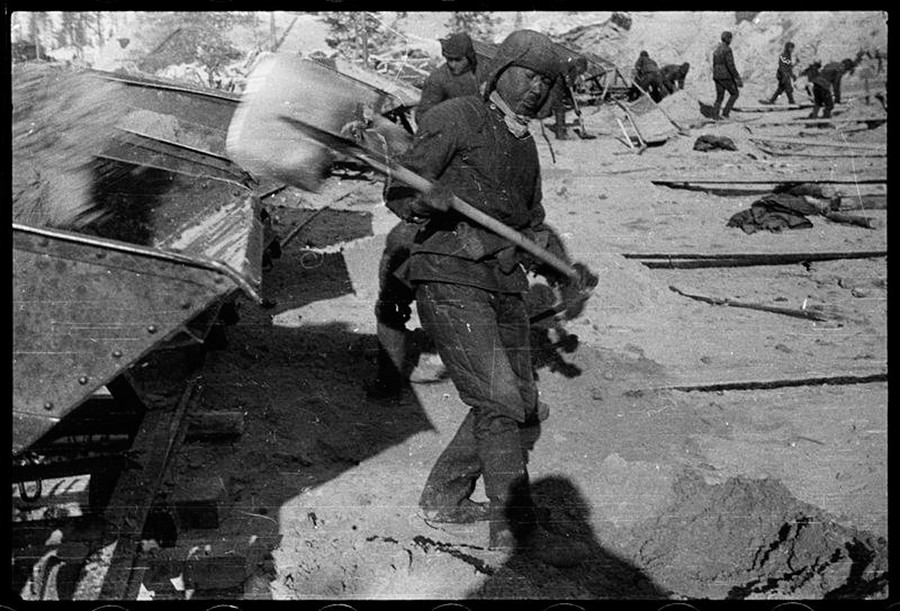

Prisoners working on the White Sea-Baltic Canal

Alexander Rodchenko/MAMM/MDFOne of the main projects implemented by Frenkel was the White Sea-Baltic Canal (Belomorkanal). Built in record time - less than two years (1931-33) - it was 141 miles long. Up to 108,000 prisoners worked on it at a time and about 12,000 of them perished.

Construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal

Alexander Rodchenko/MAMM/MDFAnother large scale construction project, the Baikal-Amur Mainline railway (BAM), dragged on until the 1980s and was completed by Soviet young people now freely choosing to work there. But it was started by Frenkel. There were already many camps scattered around the Far East where prisoners mined ore and rare metals, and even worked at uranium mining sites.

The railway was to link many sites and ease the process of developing the country’s natural resources. Six new camps were set up in the Far East for BAM. More than 150,000 prisoners embarked on its construction in the most difficult northern conditions in 1938. They built the first few stretches, but the project was halted because of World War II.

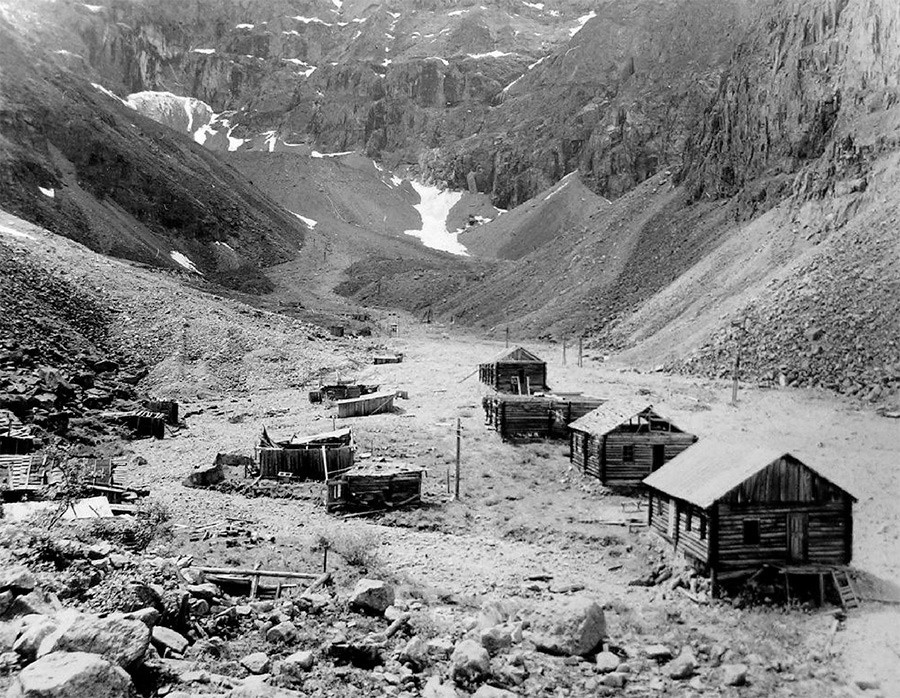

Houses of the Baikal Amur camp guards

BAM History MuseumApart from the use of slave prisoner labor, the evil genius Frenkel dreamt up another innovation - a differentiated prisoner diet. Back in the 1920s the ration had been the same for all arrestees, but under the "Frenkel method" rations were issued in accordance with the degree to which prisoners met their work targets (which were frequently set unrealistically high).

The final triumph of an evil genius

Frenkel is remembered by contemporaries as power-loving and demanding, but at the same time as a very well-read man endowed with a phenomenal memory. Even on the White Sea Canal construction site he used to go around foppishly with a walking cane, and he had a "sinister Hitler moustache".

In 1947, Frenkel, by now an NKVD general, was retired on health grounds. Historian Vadim Erlikhman believes Frenkel left the service feigning a serious illness since he felt that the clouds were darkening over him at a time when anti-semitism was on the rise in the USSR.

He lived out his final years modestly and even a little secretively, evidently afraid that the security authorities would come looking for him. Erlikhman writes that Frenkel kept a "prison kit" containing dried bread and a change of underwear under his bed. He did not go into details about his former line of work, and merely used to say that he had built roads. He did not leave any memoirs, either. Frenkel was lucky not to end up inside the system that he had himself devised in such detail. Many of his colleagues from the repressive system were not so lucky. He is known to have died of natural causes in his Moscow flat aged 76. "His peaceful death in 1960 was the final triumph of Naftaly Frenkel," Erlikhman wrote.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox