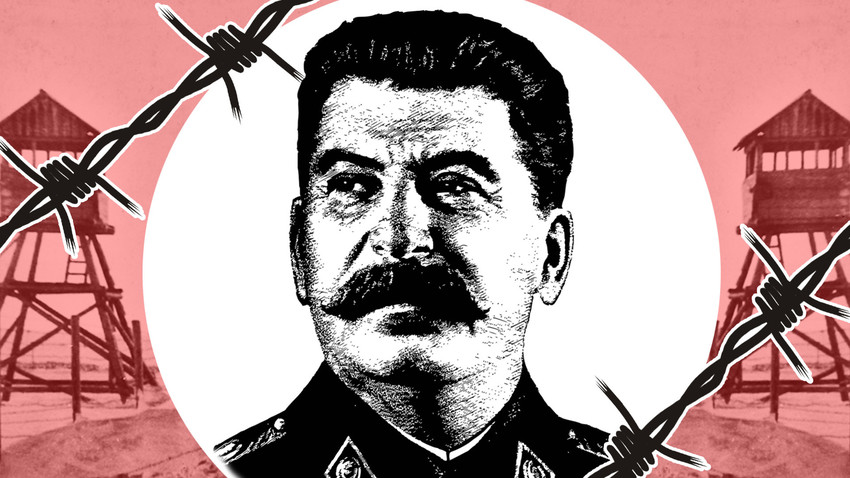

8 of the most EVIL Gulag camps of the USSR

Stalin's empire of labor camps covered all of the USSR in the 1930s-1940s.

Pixabay“Gulag” is often used to describe any Soviet prison or camp, especially in Western media. This is not quite accurate. In actual fact, the Gulag (a Russian abbreviation of General Directorate of Forced Labor Camps) came into being in 1930, lasted 30 years, and was officially terminated in 1960.

The essence of the Gulag, however, remained immutable as “a state within a state” incorporating more than 30,000 places of detention. The Gulag is strongly associated with the name of a certain Joseph Stalin: It was under his reign that a system was created whereby millions of prisoners were forced to build cities, canals, and factories, mine gold and uranium, and develop the uninhabitable territories beyond the Arctic Circle and in Kolyma.

According to data from the Gulag History Museum, 20 million prisoners passed through the camps and prisons in this system. At least 1.7 million people perished from hunger, exhaustion, illness, or a bullet to the head. They included both real criminals and innocent victims charged with “political” offenses.

To describe all the Gulag camps in one text would be an impossible task, but we’ve identified some of the most terrible, most densely populated, and most important for the Soviet economy. What were they like?

1. Solovetsky special purpose camp (Solovki)

This beautiful place, an island in the White Sea famous for its monastery, hosted the first Soviet labor camp.

V,Krechet/SputnikLocation: Solovetsky Islands (1,400 km north of Moscow)

Period of existence: 1923-1933

Max. number of prisoners: 71,800

The “grandfather” of all Soviet camps, strictly speaking, Solovki existed long before the Gulag. It was essentially a testing ground for the use of mass prison labor. “The use of prison labor arose from there,” Leonid Borodkin, head of the Center for Economic History at Moscow State University, told radio station Echo of Moscow.

On the icy islands in the White Sea, tens of thousands of prisoners felled trees, built roads, and drained swamps. At first, the regime was relatively “soft” — but by the late 1920s it had become a genuine hellhole. Uncooperative prisoners were beaten with sticks, drowned, and tortured. Alexander Solzhenitsyn in his exposé work The Gulag Archipelago described Solovki as a “polar Auschwitz.”

In the early 1930s, Solovki was disbanded, and the prisoners were moved to other camps. The test had proven successful — and the time had come to expand the system across the entire gigantic country.

2. White Sea-Baltic forced labor camp (Belbaltlag)

Prisoners building the White Sea-Baltic Сanal.

Public domainLocation: Karelia (1,100 km north of Moscow)

Period of existence: 1931-1941

Max. number of prisoners: 108,000

The history of “great communist construction projects” — large-scale endeavors using forced labor — began with Belbaltlag. The new camp was tasked with connecting the White Sea to Lake Onega via a 227-kilometer canal.

Belbaltlag prisoners slaved hard to complete the near-impossible job, and by the summer of 1933 the canal was ready. The working conditions could hardly have been worse: the only tools were shovels, picks, and other handheld implements — no heavy equipment. Those who failed to fulfill their targets were put on reduced rations and given longer sentences. According to official figures alone, 12,000 people died in the construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal.

“The White Sea-Baltic Canal helped to ‘normalize’ the Gulag in the eyes of the public,” notes the newspaper Novaya Gazeta. It was followed by other forced labor projects in which thousands more convicts toiled and died. As for Belbaltlag, the camp lasted until 1941 before being disbanded to free up labor for the Great Patriotic War.

3. Baikal-Amur corrective labor camp (Bamlag)

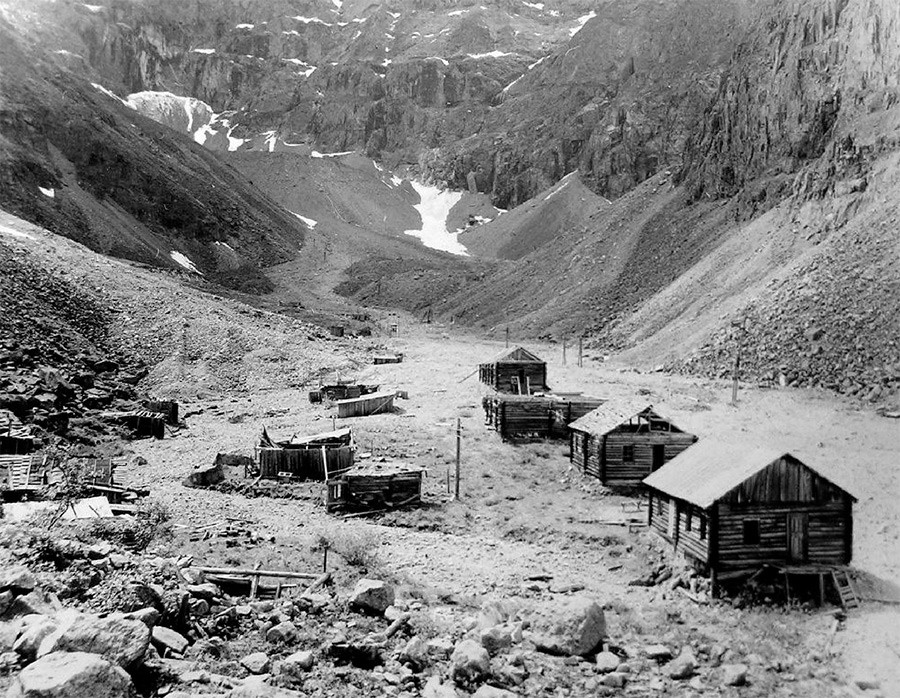

Houses where guards securing the prisoners of Bamlag used to live.

BAM History MuseumLocation: Amur Region (7,700 km east of Moscow)

Period of existence: 1932-1938

Max. number of prisoners: 200,000

Even compared to other Gulag construction projects, the Baikal-Amur Railway (BAM) was gargantuan: the plan was to build 4,000 km of railway from Taishet in Siberia to Sovetskaya Gavan on the edge of the Russian Far East. Prisoners were shipped in from all over the USSR to work on the project.

“Like everywhere else, the law here was enforced with an iron fist: No work, no food.” Whenever construction fell behind schedule, the camp administration immediately lengthened the working day. People labored 16 or even 18 hours a day,” writes historian Sergei Papkov in his book Stalinist Terror in Siberia. But because slave labor was inefficient, and the environment forbiddingly hostile, BAM never got built before the war, whereupon the project was shelved until the 1980s — when it would be completed, but not by convicts.

4. Dmitrovsky corrective labor camp (Dmitrovlag)

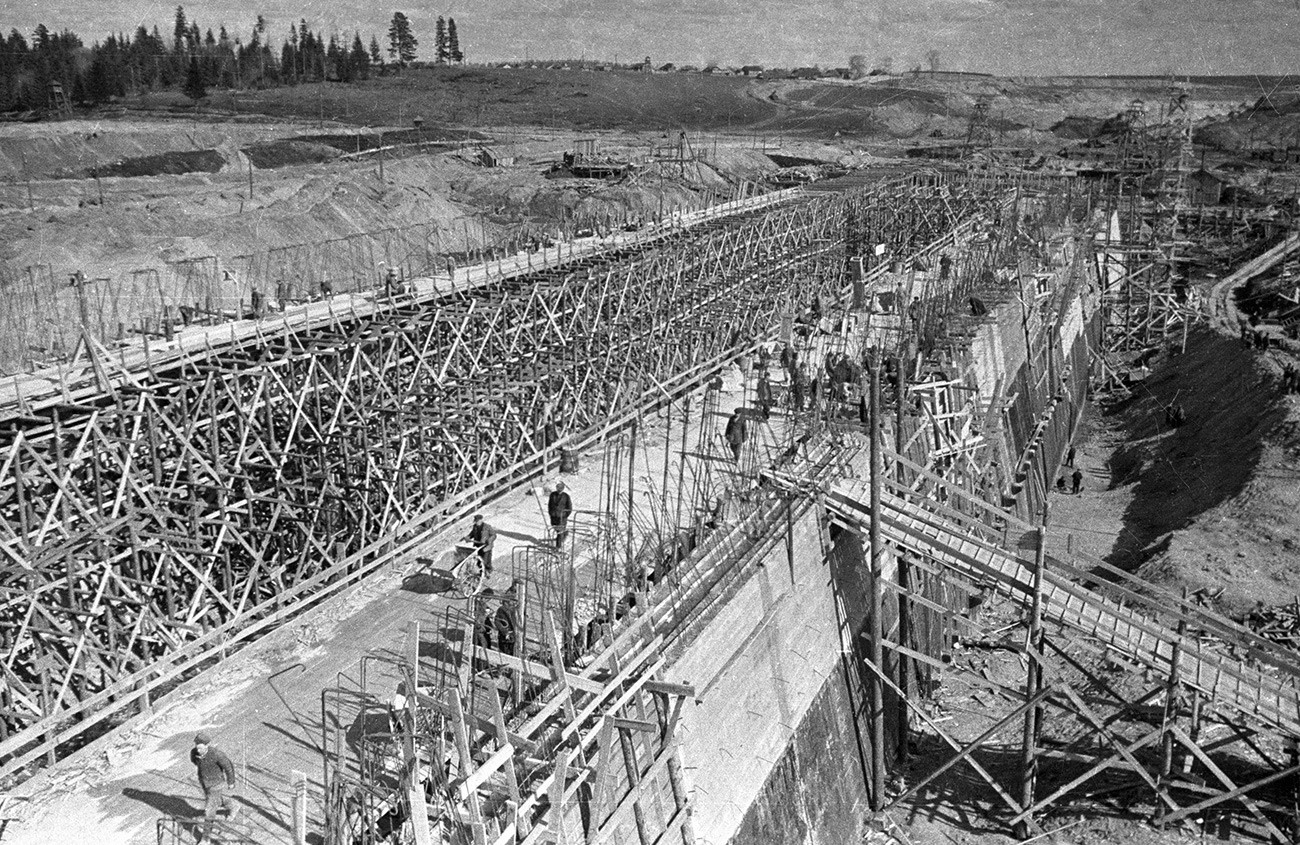

Workers constructing the Moskva-Volga Canal.

SputnikLocation: Moscow Region

Period of existence: 1932-1938

Max. number of prisoners: 192,000

Another major construction project involving Gulag prisoners was the construction of the Moskva-Volga Canal. The labor was again ferocious, yet compared to other camps the conditions were considered breezy.

“Dmitrovlag was a kind of Gulag showcase. The mortality rate was relatively low, workdays were offset, and there were a salary and early release,” explains Ilya Udovenko, a senior researcher at the Gulag History Museum. This was partly due to its proximity to Moscow: It is one thing for thousands of convicts to die in the remote forests of Siberia, but another if residents of the capital can see it.

5. North-East corrective labor camp (Sevvostlag)

Prisoners building a road in Kolyma.

Public domainLocation: Kolyma (10,300 km east of Moscow)

Period of existence: 1932-1952

Max. number of prisoners: 190,000

The opposite of the “metropolitan” Dmitrovlag was Kolyma. The USSR gave short shrift to camp inmates dispatched to the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk to mine gold and tin, and build infrastructure capable of withstanding the brutal climate from scratch (it was in the 1930s that the regional city Magadan was built).

The Sevvostlag camp was the focal point for the development of Kolyma; it was run by Dalstroy, a state trust for the development of the Far East. Legally, Dalstroy was not considered part of the Gulag, but the camp conditions in the late 1930s were no easier.

“To turn a healthy young man into a physical wreck takes 20-30 sixteen-hour days, seven days a week, with permanent hunger, ragged clothing, and nights spent in -60°C frost in a hole-ridden tarpaulin tent... This has been verified many times,” Varlam Shalamov, who spent more than ten years there, wrote about the Kolyma camps. According to Russian reports, at least 150,000 people died in the Kolyma camps.

6. Norilsk corrective labor camp (Norillag)

Prisoners of Norillag working in permafrost.

Public domainLocation: Norilsk (2,800 km north-east of Moscow)

Period of existence: 1935-1956

Max. number of prisoners: 72,000

Now home to 179,000 people, Norilsk is the largest polar city in the world. But back in the 1930s, like Magadan, it was built by Gulag prisoners. Soviet industry needed metals, and Norilsk sprang up around a copper-nickel plant, also operated by prison labor.

“The Norilsk camps were not the worst in the Gulag system,” says local journalist Stanislav Stryuchkov. “Prisoners in Norilsk were always seen as vital work tools, a means to fulfill the plan.” As a rule, the Norillag camp received relatively young and healthy prisoners able to work in the Far North climate. For this reason, the mortality rate at Norilag was lower than in Kolyma or on the BAM construction project.

7. Vorkuta corrective labor camp (Vorkutlag)

Location: Vorkuta (1,800 km north-east of Moscow)

Period of existence: 1938-1960

Max. number of prisoners: 72,900

Vorkuta is another polar city built by Gulag inmates. The history of the Vorkutlag camp is very similar to Norilsk, except that the town-forming enterprise here was a coal plant. But during the war, Vorkutlag acquired special significance — it not only supplied the country with coal but took in “especially dangerous” criminals sentenced to hard labor.

The production quotas were forever going up, and the work conditions were back-breaking. Prisoner discontent reached boiling point in 1942 when the Ust-Usa uprising broke out at one of the camp sites. “It was the only armed action by prisoners during the entire war,” comments historian Nikolai Upadyshev on the insurrection. Having disarmed the guards, hundreds of prisoners seized their weapons and tried to incite rebellion among the inhabitants of the surrounding villages. The revolt was ultimately put down by NKVD troops.

Read more about the Ust-Usa uprising here.

8. Karaganda corrective labor camp (Karlag)

Karlag.

Public domainLocation: near Karaganda, Kazakhstan (3,000 km east of Moscow)

Period of existence: 1931-1959

Max. number of prisoners: 65,000

Unlike the camps linked to the “great construction sites,” the Soviet government established Karlag as a permanent facility. Karlag prisoners had the task of providing food, clothes, and other products for the whole of northern Kazakhstan. “The work of the camp inmates was never-ending: in summer they farmed the land, in winter they worked in plants and factories,” writes Kazakh newspaper Vlast.

Karlag received “political” exiles en masse, including members of deported peoples and those suspected of collaborating with the Germans during the war. It also encompassed the infamous ALZHIR (Akmola camp of wives of traitors to the homeland), where the wives and children of those convicted of treason against the USSR were kept. According to Soviet law, being related to a traitor was also a crime. Some were even “lucky” enough to be born in the camp: in the period 1931-1959, 1,507 babies were delivered at Karlag.

Prepared with the assistance of the Gulag History Museum.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox