How the U.S. deported its radicals to Soviet Russia

Long before the famous “Russians are coming!” hysteria during the Cold War, the U.S. was struck by the “Commies are coming!” panic of the late 1910s. The 1917 Russian Revolution not only changed Russia, it also deeply influenced American society, generating fear that the communists would come to power there as well.

Labor Day parade in New York

Public domainThe Red Scare

Relations between the U.S. government and left-wing and anarchist movements had never been perfect, but in 1919 they literally turned into a war. In June, the Italian anarchist followers of Luigi Galleani detonated bombs in eight American cities, targeting judges, immigration officials, and attorneys.

Luckily, no one was harmed, but the country was gripped by the fear that it was on the eve of a Russian-style revolution and civil war. One of the intended victims of the June attacks, attorney Alexander Mitchell Palmer, told Congress that revolutionaries were ready to “rise up and destroy the government at one fell swoop.”

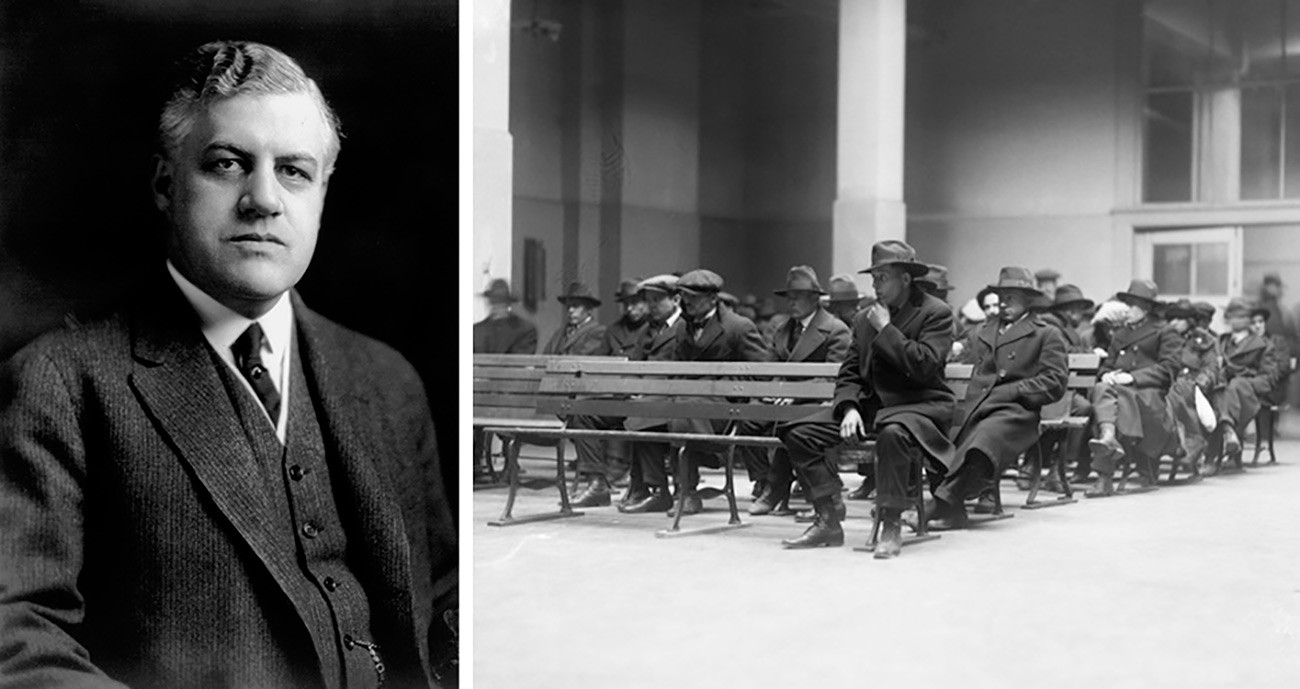

Alexander Mitchell Palmer/Men arrested in raids awaiting deportation hearings

Public domainIt was Palmer, with his assistant, the future first FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who organized the so-called Palmer Raids, a series of arrests of radical leftists and anarchists. Since the lion's share of the latter were immigrants from Western and Eastern Europe, the government used the effective method of deporting these non-citizens from American soil.

Soviet Ark

On December 21, 1919, 249 arrested radicals were put on board the USAT Buford in New York harbor and secretly sent to Russia as “America’s Christmas present to Lenin and Trotsky.” The families of the deportees were given notice of their relations’ expulsion only after the ship had set sail.

The newspapers were jubilant. It was them who gave the ship its biblical nickname: “Just as the sailing of the Ark that Noah built was a pledge for the preservation of the human race, so the sailing of the Soviet Ark is a pledge for the preservation of America,” the New York Evening Journal wrote.

USAT Buford

Public domainThe Saturday Evening Post shared the same feelings: “The Mayflower brought the first builders to this country; the Buford has taken away the first destroyers.”

To Soviet Russia

Since back then the U.S. and Soviet Russia had no diplomatic relations, the ship was sent to Finland. The Soviets were informed of the journey and were very much looking forward to receive the honorable guests. Of particular interest for them were the anarchist leaders and ideologists Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman, whom J. Edgar Hoover called “the most dangerous woman in America.”

Goldman, known also as “Red Emma,” recalled: “For 28 days we were prisoners. Sentries at our cabin doors day and night, sentries on deck during the hour we were daily permitted to breathe the fresh air. Our men comrades were cooped up in dark, damp quarters, wretchedly fed, all of us in complete ignorance of the direction we were to take. Yet our spirits were high-Russia, free, new Russia was before us.”

Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman around 1917-1919

Public domainThe ship landed in Finland, where the so-called Ark’s passengers were escorted by the Finnish military to the Soviet border. Most of them had been born in the Russian Empire, fought against Tsarism, and been forced to leave the country. Now, much inspired, they hoped to stay in the Land of the Soviets forever. The reality, however, turned out to be not so bright as they had expected.

Disillusions

Warmly greeted by the Bolsheviks, the Soviet Ark passengers began to settle into Soviet life. The fate of most of them remains unknown, but the paths taken by the key figures can be followed.

As Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman traveled across the country, meeting Lenin, leading Bolsheviks, and ordinary folk along the way, they became much disillusioned with what they saw. Horrified by the actions of the Cheka secret police, Berkman wrote in his book The Russian Tragedy: “From the intended defense of the Revolution the Cheka became the most dreaded organisation, whose injustice and cruelty spread terror over the whole country.”

Suppression of the Kronstadt Rebellion

Public domain“I found reality in Russia grotesque, totally unlike the great ideal that had borne me upon the crest of high hope to the land of promise,” says Emma Goldman in My Disillusionment in Russia: “I saw before me the Bolshevik State, formidable, crushing every constructive revolutionary effort, suppressing, debasing, and disintegrating everything.”

The final straw was the suppression of the Kronstadt Rebellion of sailors in 1921. “The pride and glory of the Revolution,” as Trotsky called them, the sailors demanded the cessation of the Bolshevik dictatorship and the restoration of political freedoms for all socialist movements in the country.

Soon after the rebellion was brutally suppressed, Goldman and Berkman left the country, never to return.

Soviet martyr

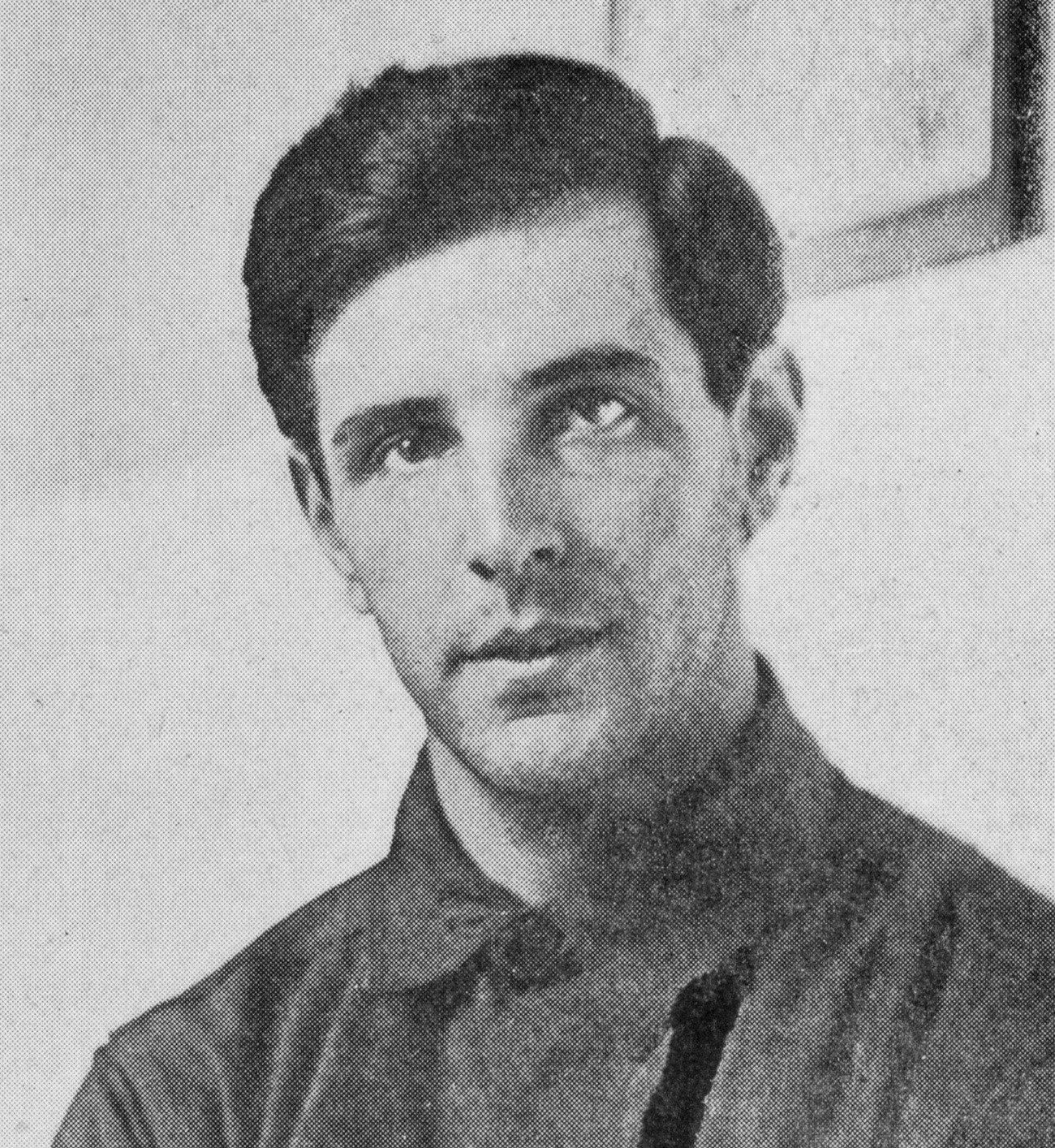

Peter Bianki

Public domainHowever, not all the Soviet Ark passengers became disillusioned with their new homeland. Peter Bianki, leader of the once powerful Union of Russian Workers in the U.S., found a place for himself in Soviet Russia as well.

Bianki immediately threw himself into all kinds of work for the Soviet Republic: he restored the transportation system in Siberia that had been damaged during the Civil War, and served as a city government official in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) and even as a deputy commissar aboard a hospital ship in the Baltic Sea.

On March 10, 1930, Peter Bianki was killed along with ten other Communist Party activists and officials during one of the anti-Soviet uprisings in the Altai region. All of them were proclaimed as Soviet martyrs.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox