Why didn’t the USSR join Allies in 1939?

Soviet leaders (Stalin, Molotov, Voroshilov) faced some tough choices in 1939.

Pavel Kuzmichev; Fedor Kislov/МАММ/russiainphoto.ruBy spring 1939, the situation in Europe was rough. The appeasement policy the United Kingdom and France championed, trying to make Adolf Hitler more peaceful by satisfying his growing appetites, had failed completely.

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and French Prime Minister Eduard Daladier ‘let’ Germany have Austria Anchlussed (ie. annexed), then forced Czechoslovakia to give up its German-populated region of Sudetenland to Hitler, as well. Chamberlain, returning from Munich where they signed a treaty with Hitler, boasted he had returned “with peace for our time”. However, just half a year later, in March 1939, Hitler broke the treaty and had the rest of Czechoslovakia occupied. Now it was clear that appeasing Germany was impossible – and the West finally reached out to Moscow.

Hints from Stalin

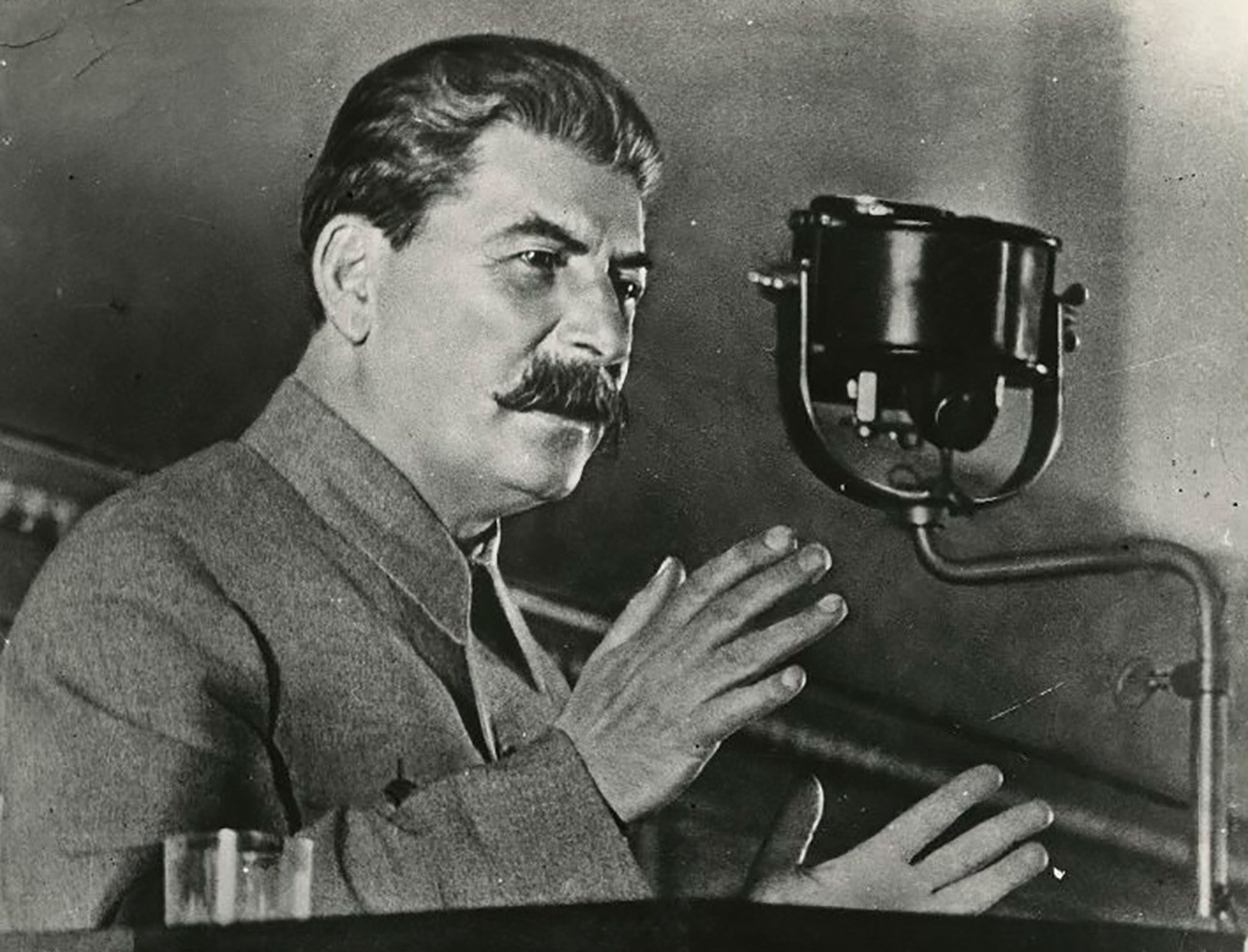

Joseph Stalin.

Emmanuil Yevzerikhin/МАММ/russiainphoto.ruSeveral days before German troops occupied Czechoslovakia, Joseph Stalin made a speech during the Communist Party Congress in Moscow. “Aggressor states are waging a war, violating the interests of non-aggressive states, particularly England, France and the U.S… We support nations who fell victims to aggression and fight for the independence of their homelands,” he said.

It was a clear hint that Moscow was ready to talk with Western democracies – though the Soviet Union still considered them hostile capitalist nations. Stalin understood that the USSR badly needed an alliance with Britain and France to escape facing the Axis’ power all by itself. Shaping a two-front coalition against Hitler in 1939 seemed to be a decent option to stop him.

After Hitler had spat in the face of all his previous agreements with Britain and France by taking Czechoslovakia, the West also understood the danger very well. Yet, it was still hard to forge an alliance – as Britain, France and, most importantly, USSR’s neighbors, feared Stalin more than Hitler.

Disputes

Adolf Hitler shaking hands with Neville Chamberlain. Giving up Czechoslovakia was one of the biggest mistakes in the history of Britain's international relations.

Getty ImagesNeville Chamberlain, who played a crucial role in shaping the policy of Western democracies, especially hated Communism; the sheer idea of cooperating with Stalin repulsed him. “I must confess to the most profound distrust of Russia. I have no belief whatever in her ability to maintain an effective offensive, even if she wanted to. And I distrust her motives, which seem to me to have little connection with our ideas of liberty,” he wrote to a friend in March 1939.

Why was Chamberlain so stubborn? It wasn’t just about his anti-Communist stance. The point was there was no direct border between Germany and the USSR in spring 1939: in case the Red Army had had to fight Nazi Germany, either Poland or Romania would have to let them through their territory – something they were very unwilling to do.

“Actually, the Soviet Union had territorial disputes with both Poland and Romania [over West Ukraine and West Belarus and Moldova, respectively],” says historian Oleg Budnitsky, director of the International Center for the History and Sociology of World War II. “So both those states feared that Soviet forces, once let onto their soil, would not go away.”

As Britain and France guaranteed their help to Poland and Romania, Chamberlain was uneager to pressure his allies. Nevertheless, a large part of the British public thought the other way: future PM, Winston Churchill, gave an eloquent speech in the Senate, claiming that “there is no means of maintaining an eastern front against Nazi aggression without the active aid of Russia.” According to national polls of June 1939, 84% of the British favored an Anglo-French-Soviet military alliance. So, Chamberlain and Daladier reluctantly began negotiations with Stalin.

Underrepresented talks

From June 15 to August 2, British, French and Soviet representatives gathered in Moscow, to decide on political terms of the possible convention. What had they agreed on after two months of arguing? According to the project, all three powers would give each other - and any state bordering Germany (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Turkey, Greece and Belgium) - guarantee of military help in case of German aggression.

They reached a preliminary agreement – but when it came to the direct talks between military missions, everything quickly collapsed. While the USSR was represented at the negotiations by Marshal Kliment Voroshilov, the Soviet Minister of Defense and Stalin’s close associate, Britain and France only sent minor military officials to Moscow: Admiral Reginald Drax and General Aimé Doumenc, who weren’t even authorized to make any decisions without their government’s approval.

Instant dead-end

Admiral Reginald Drax and General Aimé Doumenc in Moscow.

Sputnik“The Soviets were appalled with such low representations, so they didn’t even consider those talks seriously,” says Oleg Budnitsky. Moreover, the negotiations stalled immediately after Voroshilov had asked if Poland and Romania would let the Red Army through their territories to fight Germany. Drax and Doumenc didn’t have the competency to answer such a principal question – of course, Poland and Romania would not agree. “Stalin believed that those states were just puppets and that Britain and France could force them to agree – but it was more complicated than that and led to London and Paris failing to convince Warsaw that the USSR was any better than Germany,” Budnitsky notes.

Kliment Voroshilov.

Ivan Shagin/SputnikVoroshilov was quite brief. “The Soviet mission considers that without a positive answer to this question all the efforts to enter into a military convention are doomed to failure,” he said, inviting Drax and Doumenc to enjoy their time in Moscow instead. The fruitless talks were officially halted on Aug. 21, 1939.

Just two days later, German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop arrived in Moscow to sign a non-aggression treaty (which included a secret protocol about “the partition of spheres of influence” in Poland). Stalin preferred a concrete deal with Hitler, rather than the continuation of useless talks with London and Paris.

Why did he do that? Find out here!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox