Sophia Dolgorukova – a princess, pilot and taxi driver

In the late 1920s in Paris, a lot of talented Russian emigrants, including, of course, many noblemen, had to make ends meet somehow. And one could accidentally get a taxi ride with writer Gaito Gazdanov as the driver, or even a real Russian Princess – Sophia Dolgorukova, whose ancestry went back to Catherine the Great and even farther to Rurik.

Coming from two bastard lines

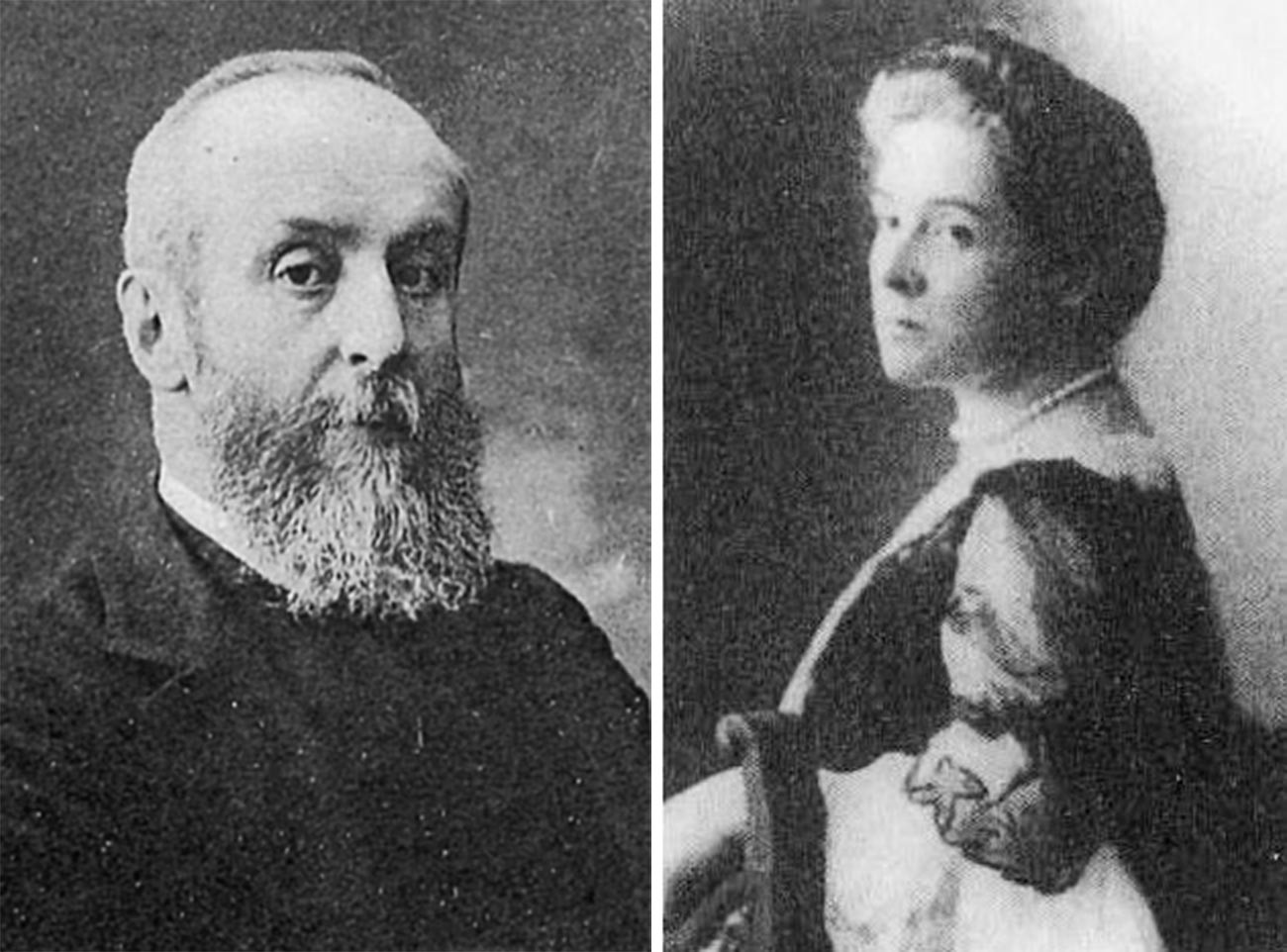

Alexander Bobrinbskiy and Nadezhda Bobrinskaya, Sophia's parents

Public domainPrincess Sophia Dolgorukova had Romanov blood in her veins. Her grandmother on the mother’s side, Nadezhda Polovtsova (1843-1908), was a bastard daughter of Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich (1798-1849). And Sophia’s father, Count Alexey Bobrinskiy (1852-1927), was the great-grandson of Count Alexey Bobrinsky, Catherine the Great’s bastard son.

Sophia’s father was a rich and influential man, member of the Governing Senate and also a renowned archaeologist. But her mother was no less remarkable – Nadezhda Bobrinskaya, born Polovtsova (1865-1920), was one of the first Russian astronomers. Born into such a family, Sophia took a liking for sciences from an early age. In 1907-1912, she studied in St. Petersburg Women’s Medical Institute, the first educational institution in Europe where women could get a higher medical education. In 1913, she volunteered as a field nurse during the Second Balkan War and was awarded personally by Peter I of Serbia (1844-1921) for her service.

Princess Sophia Volkonskaya (formerly Dolgorukova), born Countess Bobrinskaya

Public domainBut at the same time, in 1907, Sophia Bobrinskaya became a lady-in-waiting at the Russian Imperial Court. The same year, she married Prince Pyotr Dolgorukov (1883-1925), a military man. Their marriage wasn’t a happy one and although they had a daughter, Sophia, known as Sofka Skipwith (1907-1994), they eventually divorced in 1913. Even during their first years together, Sophia spent a lot of time studying and in hospitals. She didn’t like the Imperial Court with its formalities.

Sofka Zinovieff (b. 1961), British author and Sophia Dolgorukova’s great-granddaughter, says of Sophia: “Sophia’s behavior went beyond what was expected of a young woman. She was not interested in appearing at court in beautiful dresses. She always dressed simply, wearing a long skirt and blouse. She learned to drive and was generally very emancipated, which was unusual for a woman of her social status.”

Nurse, pilot, driver

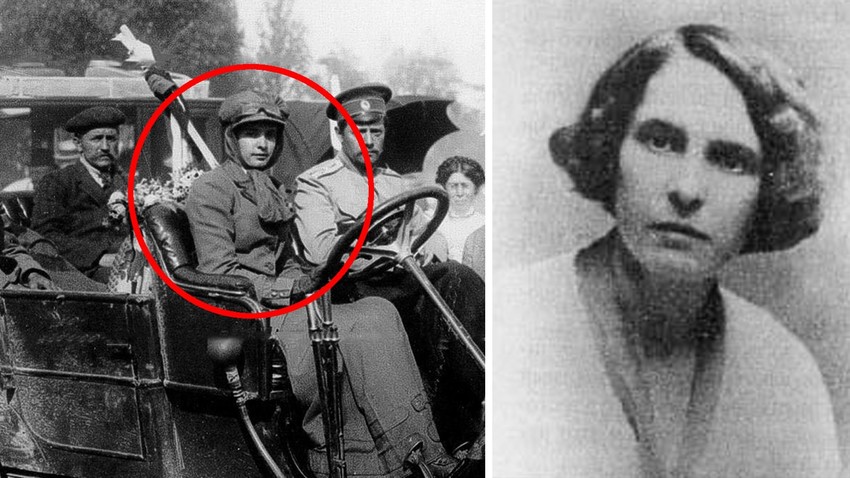

Sophia Dolgorukova behind the wheel at the Emperor Nicholas II Prize International Rally, 1910

Public domainWe don’t know where Sophia learned to drive, but at 23, in 1910, she was the only woman taking part in the first Emperor Nicholas II Prize International Rally from Tsarskoye Selo (an Imperial residence close to St. Petersburg) to Kiev and back, 3,200 kilometers in total. The rally was widely reported in the European press. French newspapers dubbed it “La Coupe du Tzar”.

The race featured about 50 teams from Russia, Germany, France and Great Britain. And Sophia Dolgorukova, as Governor of Moscow Vladimir Dzunkovsky wrote, “the only woman who took part in the race and drove the car herself all the time,” was the center of everyone’s attention. Sophia drove a 19-horsepower Delaunay-Belleville and almost crossed the finish line, but on the way back, another car damaged her automobile’s radiator, so she wasn’t able to finish the race. Still, the newspaper ‘Russkoye Slovo’ reported, “The arrival of the Princess was met with a storm of enthusiasm from the crowd. The car of the brave athlete – the first Russian female driver – was covered with flowers…”

But apparently, Sophia wanted to get even higher in terms of emancipation and, in 1912, she finished the flying school under Louis Blériot, a French aviator, the first man to perform an airplane flight across the English Channel. In 1914, Sophia received a Russian flying license and became one of the first female pilots in Russia!

A Delaunay-Belleville (1909) thet belonged to the Royal family. The boy at the wheel is Tsarevich Alexey Romanov, Nicholas's son.

Public domainAs World War I started, Sophia petitioned for an appointment to the military aviation, but her request was rejected and Princess Dolgorukova went to the front as a nurse. At first, Sophia served near Warsaw and then in Iran. But as soon as in 1917, Alexander Kerensky, Chairman of the Interim Government, granted Russian women the right to serve in the army, Dolgorukova joined the 26th Corps Air Detachment and probably performed a few combat missions. But after the Russian Empire fell to the Bolshevik rule, Sophia had to flee the country. By that time, she was known as Princess Volkonskaya.

Princess behind the wheel

Sophia Dolgorukova behind the wheel at the Emperor Nicholas II Prize International Rally, 1910

Public domainIn 1918, during a revolutionary turmoil in Russia, Sophia married another Prince – Peter Volkonsky (1872-1957), but at the same time, lost track of her daughter Sofka. Princess Sophia didn’t know Sofka, who served as a lady-in-waiting to the Dowager Empress Maria Fyodorovna (1847-1928), was evacuated in a large party of aristocrats with Maria Feodorovna to England in spring 1919. Mother and daughter were eventually reunited in Bath, England – but then, Sophia decided to return to Russia for her husband.

“Sofka already knew about my second marriage and took it as a personal insult to herself,” Sophia wrote in her memoir, ‘Vae Victis’ (Latin for “Woe to The Vanquished”), published in 1934. Nevertheless, she returned to Russia – via Finland. As Sophia arrived at St. Petersburg in 1920, she learned that her husband was in Ivanovsky concentration camp in Moscow.

The Ivanovsky monastery, where Sophia's husband was held in a temporary concentration camp in the 1920s.

Public domain“My arrival made an impression in the prison. It didn’t happen often that someone voluntarily returned to the USSR. But the wife came from abroad to help her husband, the case has not yet been,” Sophia wrote. In Moscow, she used her connections to get to Maxim Gorky and even Leonid Krasin, the Bolshevik Minister of Trade, trying to get her husband out – and visited him in the concentration camp every week. He was finally set free in February 1921. “You fully owe your freedom to your wife,” Mikhail Boguslavsky, a state security official, said to Peter Volkonsky.

Sophia and Peter first left Moscow for St. Petersburg, where they lived in Anna Akhmatova’s room in the ‘House of Arts’ on Moika Street, 59. They were so poor that they had to sell expensive French blankets and antique books Sophia had taken from her former home in St. Petersburg. They were finally able to leave Soviet Russia through Estonia the same year. Sophia was 34 at the time.

The 'House of the Arts' at Moika, 59.

Public domainTaxi driving was just one of the occupations that supported Sophia and her husband during the later years they spent in France. Even though Prince Volkonsky wasn’t fit for working day jobs, he served as a clerk and an interpreter. Sophia died in Paris in 1949. Georgy Ivanov, a Russian emigrant poet, wrote about her: “In any country, the mind, literary talent, spiritual exclusivity and energy of the late Sophia Volkonskaya would have drawn everyone’s attention to her, would have put her on a well-deserved height. In any country where she belonged. But lived in a foreign country for a long time – and died there.”

In her 1934 book, Sophia herself was rather sceptical about her later life: “Own stupidity, someone else’s dishonesty... Money, ruin, poverty... Teaching gymnastics, caring for the sick in Nice, filming as an extra, reading aloud to a blind banker, passing an exam for a taxi driver in Paris... And melancholy, endless melancholy.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox